A few of them radically changed the history of their country, while others ended up only as footnotes. Many were competent and intelligent. Others were cruel and lazy. Some of them were quite fascinating and a tad bit strange to boot.

10 Toghon Temur

Established in 1271 by Genghis Khan’s grandson, the Mongol-ruled Yuan dynasty controlled China for almost an entire century. Although the Mongol emperors adopted some Chinese customs and really weren’t radically different from their Han predecessors, their policies discriminated against ethnic Chinese and favored Mongols. In the four-tier social hierarchy of the time, Mongols sat at the top of the pyramid, followed by foreign groups like West Asian Muslims, northern Chinese, and then southern Chinese. The Mongols weren’t keen on giving up their cultural identity and generally tried to keep themselves separated from the Chinese, even enforcing different rules and laws for the two groups. This officially sanctioned discrimination upset many Chinese and made Mongol rule unpopular. The Yuan rulers were widely perceived as incompetent and decadent, and no Mongol emperor represented these unsavory qualities better than the last one, Toghon Temur. Toghon Temur, who had taken the throne when he was only 13 years old, was more interested in sex and Buddhist spiritualism than confronting the economic and natural disasters that had befallen China in the last few decades of Mongol rule. While his subjects were starving and dying from plague, Toghon Temur dressed up as a Buddhist priest and organized vast sex orgies in the Forbidden City. As rebellions broke out across China, Toghon Temur and his chief minister contemplated the bizarre idea of killing anybody with the surnames Zhang, Wang, Liu, Li, and Zhao. These were five of the most common surnames among the Chinese. Had the plan been carried out, over 90 percent of the population would have been exterminated. By 1368, a rebel Chinese army led by Zhu Yuanzhang had captured most of the country, and Togon Temur fled his palace and took refuge in Mongolia, where he died in 1370.

9 Hongwu

In the same year that the last Yuan emperor left China, the rebel leader Zhu Yuanzhang proclaimed the beginning of the Ming dynasty and took the title of Hongwu. The new emperor was a notoriously tough, paranoid, and ugly man. His early life was exceptionally harsh. After being orphaned at age 16, Zhu became a Buddhist monk and took to begging and wandering to survive. Through his travels across his home province of Anhui, Zhu witnessed the widespread starvation and suffering of the common people under Mongol rule. In 1352, Zhu joined a rebel army and quickly rose to become its leader, capturing the Mongol capital of Daidu (present-day Beijing) in 1368. Once in power, Hongwu concentrated on driving out the last of the Mongols and restoring Chinese culture and values. In 1369, he ordered public schools to be built across the country, where students would study classic Chinese texts. Later, he reestablished the bureaucratic civil service exam, an emblem of Chinese culture that had earlier been abolished by the Mongols. He also reformed the tax system and left behind an influential legal code before his death in 1398. Despite these accomplishments, Hongwu’s legacy is mostly mixed. While some historians have praised him for bringing an end to Mongol rule, others have expressed disdain for the inefficiency of his reforms and the brutal and paranoid nature of his reign. Anybody who criticized him was publicly flogged on their bare buttocks in court or sometimes even sentenced to death. Distrustful of his own officials, Hongwu was also constantly afraid that he would be overthrown. In 1380, after uncovering an actual plot by his prime minister to depose him, Hongwu abolished the office and had the man beheaded. He then went on a mad purge to kill the man’s family and anybody he suspected of plotting against him, possibly executing as many as 100,000 people.

8 Wang Mang

Some 1,900 years before Mao Zedong founded the communist People’s Republic of China, China’s first “socialist” ruler, Wang Mang, seized power from a child emperor and founded the Xin dynasty in AD 9. Wang, an ambitious and socially conscious reformer, embarked on a number of policies that many later historians have interpreted as socialistic. In an attempt to fix China’s dire economic situation and a starving and poor peasantry, Wang’s government took control of all the land in the country and ordered that rich landholders equally redistribute their estates. He also introduced price controls, banned the slave trade, and confiscated thousands of pounds of gold to weaken the power of the elite. Not surprisingly, the country’s rich merchants and nobles weren’t very enthusiastic about Wang’s new policies. The reforms only worsened China’s terrible economic crisis, and Wang called them off after only eight years. Wang’s timing, however, proved to be too late. A civil war erupted, and both the elite and the peasantry that he had tried to help took up arms against him. By the fall of AD 23, Wang realized that his situation was hopeless. As the rebels approached his capital of Chang’an (modern Xi’an), Wang lingered in his palace, consorting with magicians and trying to cast spells. On October 7 of that year, the rebels invaded Chang’an and stormed Wang’s palace. They beheaded him and then dismembered his body, bringing an end to the first and last Xin emperor.

7 Xuanzong

Xuanzong’s 43-year reign is considered the high point of the Tang dynasty (618–907), a time in Chinese history renowned for its beautiful poetry and cosmopolitan culture. Not all of Xuanzong’s time on the throne was great, however, and the later half of his reign also marked the beginning of the Tang’s decline. For most of his time on the throne, Xuanzong was a very competent ruler. After becoming emperor in 712, Xuanzong embarked on a number of successful reforms, cleaning up the bloated imperial bureaucracy and keeping the frontiers of the empire well-protected with military governors who commanded professional armies. In his later years, Xuanzong’s interest in governing declined. He used much of his time to dote on Yang Guifei, a concubine who was initially his son’s wife. Yang used her powerful influence over the emperor to advance her friends and family, helping her cousin Yang Guozhong to become prime minister. Her adopted son, An Lushan, was also made a military governor. By 755, An Lushan had a falling out with Yang Guozhong and launched a rebellion to topple the Tang government. As the rebels began to close in on the capital city of Chang’an, Xuanzong and Yang Guifei had to flee the city for safety. After stopping at a remote village, the Imperial Army came to a halt and demanded that the emperor execute Yang Guifei and her cousin for their role in instigating An Lushan’s rebellion. Faced with a revolt from his own troops, Xuanzong realized that there was no way out but to have Yang Guifei killed. The historical record varies about what happened next, but Yang either voluntarily hanged herself or was strangled to death by an imperial official. Xuanzong, devastated by his lover’s death, then gave up his throne and left the job of putting down An Lushan’s rebellion to his son.

6 Jianwen

In 1398, Jianwen succeeded his grandfather, Hongwu, as the second emperor of the Ming dynasty. This was a controversial move that had greatly angered Jianwen’s uncles, whose power he quickly moved to reduce. His uncle Zhu Di, a successful military veteran who helped keep the Mongols out of China, seized control of the northern part of the country and launched a rebellion to take the rest. After fighting Jianwen for three years, Zhu Di and his supporters invaded the imperial capital of Nanjing in 1402. Although the city went down quite easily, Zhu Di had a bit of a problem: Jianwen’s palace was destroyed during the invasion, and nobody could find his body. Zhu Di claimed that his nephew accidentally died in the palace fire, but others believed that the old emperor had escaped and left China. Four days after Jianwen allegedly died in the fire, Zhu Di declared himself the Yongle emperor. Yongle wanted his predecessor’s reign completely erased from history, going so far as to rewrite himself in historical records as Hongwu’s successor. He also launched a bloody purge across the southern side of the country, wiping out the former government’s supporters. Despite the official story of Jianwen being dead, it seems that Yongle might have believed otherwise. In 1405, when he commissioned Zheng He’s first expedition to explore the world, Yongle told the renowned explorer to look for information about Jianwen. The old emperor never popped up during Zheng He’s travels, however, and whether he really died that day in Nanjing remains a mystery.

5 Zhengde

The emperor Zhengde, also known as Wuzong, is little remembered today except for his extravagant and shocking lifestyle. With the help of his friend Jiang Bin, Zhengde enjoyed kidnapping women and raping them. In one infamous incident, after fighting a rebellious prince, Zhengde and his men raped an untold number of virgins and widows as they made their way across the city of Yangzhou. One historian said, “His violence plunged the city into such a panic that families grabbed any young men available to marry their daughters.” Zhengde eventually abducted so many women that there was no room in the Imperial Palace to keep all of them. His “Leopard Quarter,” a second palace complete with a zoo, was where he spent much of his time. The emperor’s taste for sex was endless, and it was even rumored that he had a sexual relationship with his eunuch Wang Wei. In autumn 1520, when he was 29 years old, Zhengde became sick after falling off a capsized boat and almost drowning. He never recovered from his illness and died several months later in the comfort of his Leopard Quarter. While his reign might have been short of any actual accomplishments, Zhengde’s larger-than-life personality and free spirit were celebrated in many works of literature after his death.

4 Jiajing

While many Chinese emperors survived assassination attempts by family members or rivals, only one of them was nearly killed by his concubines. Emperor Jiajing, the successor to Zhengde, reigned from 1521 until 1567. Although China enjoyed great stability under his long rule, Jiajing was also a very cruel man. In 1542, a group of Jiajing’s concubines decided that they would put an end to his tyranny. On November 27 of that year, while Jiajing was sleeping alone in a concubine’s room, 18 of his other concubines suddenly came in and ambushed him. While some girls drove hairpins into Jiajing’s crotch, others wrapped a silk cord around his neck and tried to strangle him. The emperor eventually fell unconscious, but he survived the attack because his concubines couldn’t tighten their cord hard enough to kill him. While her husband lay unconscious, Empress Fang had all of the conspirators behind the assassination plot immediately executed. After recovering from his close brush with death, Jiajing moved out of the Imperial Palace and dabbled with Daoist magic at a self-designed palace near old Zhengde’s Leopard Quarters. He then spent the next 25 years of his rule generally ignoring his duties, devoting himself instead to having sex with virgins and drinking “magic” potions made from bodily fluids.

3 Wu Zetian

Over the more than 2,000 years that China was ruled by emperors, Wu Zetian was the only woman who ever held the title. Originally a concubine of lowly origins, Wu became the empress after hatching a scheme to kill her own baby daughter. When the baby was only one week old, Wu suffocated her and pinned the death on Emperor Gaozong’s wife, Empress Wang. Since Wang often visited the baby’s nursery alone, the accusation stuck easily and she was dethroned. In 655, despite opposition at the imperial court, Wu took Wang’s place as empress. Her first act was to get rid of Wang and a concubine named Xiao, a former rival who also had her heart set on becoming empress. Without an ounce of mercy, Wu had the two women executed by having their hands and feet cut off. Their bodies were then hurled into wine jars, where they choked on the wine and drowned. Wu spent the next few decades consolidating her power and ruling behind the scenes. It was not until 690, after Gaozong was long dead and she forced two of her sons off the throne, that Wu became the official emperor of China. While historians have traditionally criticized her as a violent ruler, her reputation has improved in recent times due to the stability of her reign, her reform of the civil service examinations, and her policy of keeping nationwide suggestion boxes in which ordinary subjects were allowed to criticize government officials. Still, Wu’s ruthless attitude and secret police force made her many enemies during the time, and she was eventually forced off the throne after a coup in 705 by one of her sons.

2 Taichang

The death of Taichang, a Ming-era emperor who ruled for little more than a month in 1620, is said to be one of the dynasty’s greatest mysteries. After taking the throne on August 28 of that year, Taichang suddenly fell sick a few days later. Within two weeks, he had become so weak that he couldn’t sleep or walk. By September 25, Taichang was desperate to try anything. Li Keshao, a man recommended to the emperor by 13 of his officials, gave and personally prepared for Taichang a special red pill. Miraculously, the emperor began to recover after taking Li’s pill. He could sleep again, and he regained his appetite as well. When the evening came, Taichang relapsed and was given another pill. A second dose failed to improve his condition, however, and the emperor died by early morning. Taichang’s sudden death caused a great deal of controversy. Some cried of a conspiracy, accusing Li and the 13 officials who had visited Taichang the day before his death of assassinating him. It seemed strange that Li, a man with no real medical training, was allowed to give his mysterious red pills to Taichang. It sooned surfaced that Taichang was given a laxative by an eunuch around the time that he started to get sick. There was also a rumor, earlier denied by Taichang himself, that an old concubine of his father named Zheng had deliberately worsened his health by sending off eight palace maids to have sex with him. Zheng, a palace woman who wanted to become empress, was alleged to have acted in a plot with another palace woman and some other power-hungry officials to get rid of Taichang. Whether Taichang died from taking Li Keshao’s medicine, either accidentally or deliberately, has never been established.

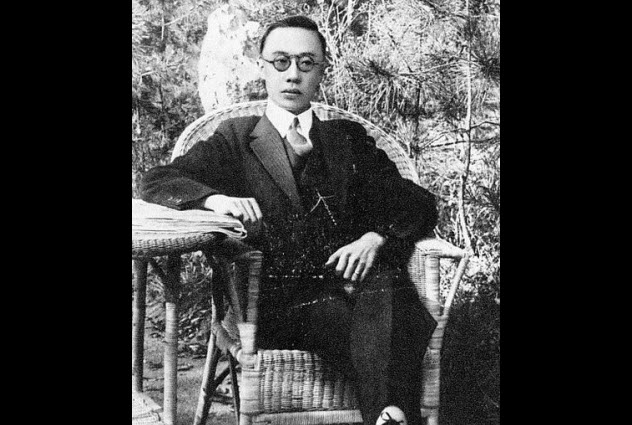

1 Xuantong

Xuantong, better known by his personal name of Henry Puyi, was the last emperor of China. At age 3, Puyi took the throne after the death of his uncle Guangxu in November 1908. Puyi’s dynasty, the Manchu-led Qing, had been in a long decline at this point. In October 1911, a democratic revolution broke out, and Puyi abdicated only a few months later as part of the peace negotiations. After more than 2,000 years as a monarchy, China was now a republic. Although he was now powerless, Puyi was allowed to keep his title as the Xuantong emperor, and the new republican government also let him live in his old palace in Beijing with an annual allowance. Aside from a 12-day restoration of the monarchy in 1917, Puyi’s life was pretty uneventful until he was forced to relocate to the city of Tianjin in 1924. During that time, Tianjin was divided up into a variety of different foreign concessions and Puyi stayed in the Japanese part of the city until 1931. By 1932, the Japanese were in control of Manchuria, the ethnic Manchu Puyi’s ancestral homeland. The Japanese invited Puyi to assist as “chief executive” of the puppet state they established there, now known as Manchukuo. After two years in power, Puyi was made emperor of Manchukuo, a move which enraged his former Chinese subjects. Once World War II was over, the Soviets abducted Puyi and held him as a prisoner in the USSR for five years. Puyi was terrified to go back to China because he was considered a war criminal for helping the Japanese, but the Soviet authorities denied his request to stay in the country for good. In 1950, the Soviets returned Puyi to China, where he stayed in prison for almost a decade. After being released, Puyi worked as a gardener at the Beijing Botanical Garden. He spent the last few years of his life quietly working at this job, releasing a ghostwritten autobiography and dying of cancer in 1967.