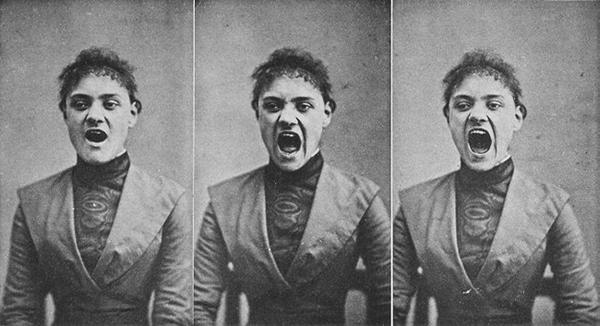

In 1862, French neurologist Guillaume Duchenne wanted to test the popular theory that the face was directly linked to the soul. He had already done some work applying electric shocks to patients’ damaged muscles and he reasoned that if he could apply electric currents to a subject’s face he could stimulate the muscles and photograph the results. One problem was that while it was easy to activate physical responses with electric shocks, most people relaxed immediately the jolt had passed through, too quickly for a camera to record it. One of the patients at the hospital where Duchenne worked was a shoemaker suffering Bell’s Palsy. A of the manifestations of the disease was facial paralysis, which meant the shoemaker would hold his expression for a few minutes after receiving the electro-shock treatment; long enough that is for the photographer to record his expression. Duchenne subjected the shoemaker to over 100 sessions, applying electrodes to various parts of his face to extract the gamut of emotions. Meanwhile, Paul Tournachon, brother of the famous Felix Nadar, snapped away. The results were published in The Mechanism of Human Physiognomy (Mecanisme de la physionomie Humaine). If the photographs look horrific you have to imagine what the poor shoemaker endured. Still, something good came out of the experiments. Duchenne was able to determine that when a person expressed a genuine smile particular muscles were activated. In physiology the authentic smile is called the Duchenne smile. People who don’t use these muscles when they smile may be showing symptoms of sociopathy.

In the second half of the 19th century an epidemic of hysteria swept across Europe and America. Women in particular were struck down with paralysis, they could not find the energy to get out of bed or they complained of obstructions in their throats. At Salpêtrière Hospital in Paris, Jean-Martin Charcot, a former student of Duchenne’s, set about finding an explanation for the condition. He had two major breakthroughs. One was that the condition was linked to some trauma in the past, the other was that men also suffered from it. His student, Sigmund Freud, would take his researches further. In 1878 chemist Albert Londe was hired as the medical photographer at Salpêtrière and began working closely with Charcot. One of their projects was to photograph patients undergoing hysterical seizures, a question being whether there was a link between the convulsions and the facial expression. To photograph the cycle of a seizure, Londe invented a chronophotographic camera. The first model had nine lenses, a later one twelve and a current activated by a metronome triggered both. With these cameras he was able to record the seizures years before motion pictures arrived on the scene. In the end, Charcot decided photography wasn’t helping him get any closer to a solution and stopped using it. Londe would later get credit as one of the pioneers of cinematography.

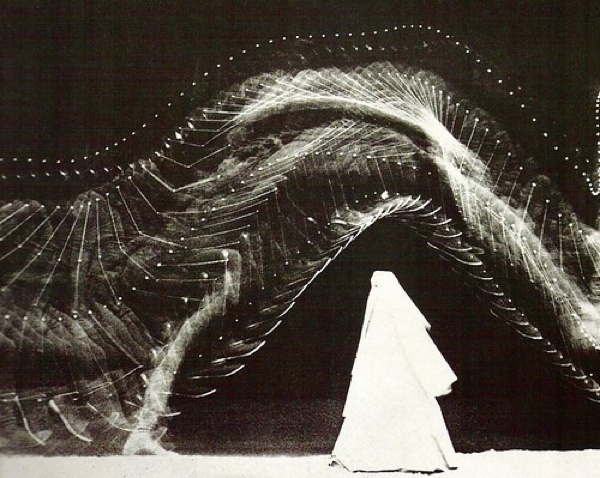

An occasional collaborator with Londe, Marey invented some important medical instruments, including a highly accurate sphygmograph for recording pulse beats. He was also a pioneer in aviation research and the Wright brothers acknowledged a debt to him. He is best known however for his chronophotographs. A century before CGI he was attaching small light globes to subjects’ bodies and photographing them against a dark background. As it happens, he didn’t think his images were all that important in the end. Two years before Eadweard Muybridge produced his famous sequence of a trotting horse, Marey had already recorded a horse’s gait but he transferred his results to a bar graph that needed some expertise to read. When he saw Muybridge’s photographs in a magazine he realized anyone could understand the information in them. He was much more experimental than Muybridge. Some of his cameras were multi-lens apparatuses like Londe’s, others were able to expose multiple images on the same plate. One of his cameras was a rifle that he used to photograph sequences of birds in flight. Around the turn of the century, Raymond Duchamp-Villon worked at Salpêtrière Hospital. One evening he brought some of Marey and Londe’s photographs home and showed them to his brother, Marcel. Twelve years later Marcel Duchamp exhibited Nude Descending a Staircase, a landmark in western art.

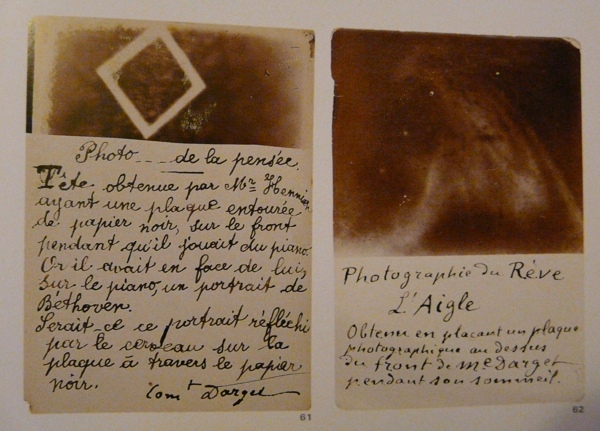

Meanwhile, back at Salpêtrière, Hippolyte Baraduc wanted to go beyond the ordinary problem of photographing hysterical attacks. Along with Louis Darget he wondered if he could photograph images of thoughts. This wasn’t as deluded or fraudulent as it may first seem. The recent invention of x-rays showed that the bones could be photographed and there was speculation that thinking created a form of electrical impulse. In an age when anything seemed possible, surely it was just a matter of fitting the pieces of a jigsaw together. Among their experiments they tried taping a piece of film to a subject’s forehead and attaching an induction coil between a subject and a camera in the hope the high voltage pulses would throw up something. Though both were sincere, it has to be said that if Darget believed he had photographed a dream involving an eagle most of his images look suspiciously like light flares. In 1909 Baraduc waited by the bedside of his dying wife, as any decent husband would. So far as sharing their last moments together, he wasn’t acting entirely out of love. At the moment she began to pass away he pressed the shutter on his camera. He just wanted to see if it was possible to catch some departing ether on the camera.

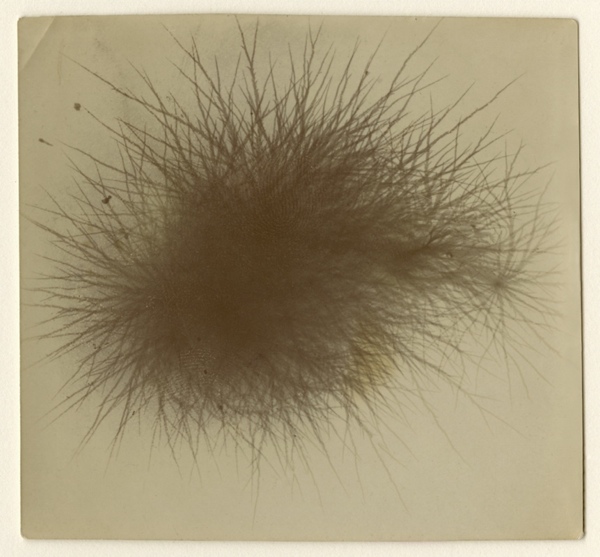

The full title in English of this photograph is, A Spark Captured on the Surface of the Body of a Well-Washed Prostitute. It sounds like a name Marcel Duchamp would give one of his artworks but Duchamp never pulled off anything this uncanny. In 1889 Polish doctor Narkiewitsch-Jodko gave a demonstration in Russia of what he called electrography. Basically he was using the same principle as Darget and Baraduc, placing an induction coil beside a photographic plate and having his subjects impress part of their body against the plate. The intense electro-magnetic pulse left a shadowy silhouette surrounded by streaks of light. Unlike the French scientists, he was not after anything as abstract as a thought. As a doctor, he wanted to know what these auras indicated about physical health. He photographed anaemics, healthy children and adults, and prostitutes. From his researches he discovered that sick people did give off weaker energy than healthy subjects. We know his process today as Kirlian photography and its association with new-age paranormal devotees has led a lot of others to dismiss it. Electrography was taken seriously in Narkiewitsch-Jodko’s time but Wilhelm Röntgen’s discovery of x-rays a few years later proved much more impressive. Electrographs might indicate a patient had a problem but x-rays could locate it. Narkiewitsch-Jodko’s work was forgotten until the 1930s, when the Kirlians revived it.

During the early years of photography things that we take for granted were serious scientific and philosophical riddles for some people. How was it for example that in a single photo, someone close to the lens who moved was reduced to a blur while someone in the distant background could be frozen mid-step? It’s said that Oliver Wendell Holmes, who invented a stereograph, used to sit at his desk and examine such photos through a magnifying glass, wondering if there was a mystery of nature everyone was missing. Normal lenses only capture between 40 and 60 degrees of the angle of view while most people see close to 180 degrees. Why was it so difficult to render the normal field of vision in a camera without distorting the image? Ask anyone to name ten great pioneers of photography and they probably won’t mention Louis Ducos Hauron, and that’s a shame. As early as 1877 he invented a color process though it was unwieldy, expensive and unlikely to catch on. In 1868 he invented the anaglyph stereoview, which produced a 3D effect when viewed through red and blue lenses. His anamorphic self-portraits were one result of his researches. In the 1880s he designed lenses that produced images which were distorted unless the viewer looked at them from the proper angle. Of course the idea was never going to be popular with the photographic public but that was beside the point. Some things just needed to be researched.

In the 1870s Charles Bennett had discovered that when gelatin was heated over several days it ‘ripened’ and one result was incredibly fast film emulsion that could reduce shutter speeds to fractions of a second. The possibilities this offered were stupendous, especially for the military, which was always interested in new technology. In 1881 Lieutenant Colonel Henry Abbott of the US Engineers commissioned a test of gelatin emulsion film at Willets Point in New York. Think about this. You are in charge of a military base with hundreds of soldiers at your disposal. To test a high speed camera a photograph of a man running on the spot or even doing somersaults would be impressive. Instead, several sticks of dynamite were strapped to a mule’s head. A wire linked the explosives to an ‘electro-magnetic machine” and the camera shutter. The moment the dynamite detonated the camera shutter fired off at 1/250th of a second. Great.

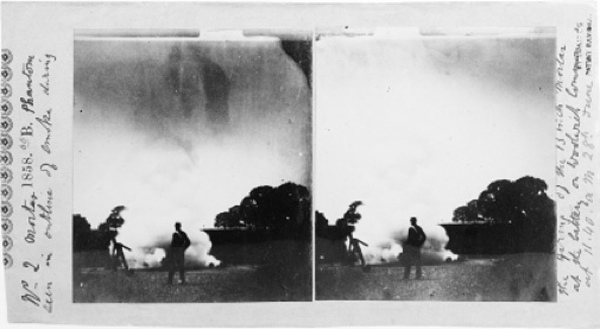

This one might not look particularly strange but it is 1858, we are still in an age when people have to sit still for up to a minute to have their portrait taken, and Thomas Skaife has just photographed a ball erupting from a cannon. What’s more, he did it with a camera he built at home. He achieved the photo by a loosely attaching a thin wire over the mouth of the cannon barrel and attaching it to an electric clock then the camera. When the ball hit the wire it broke contact, setting off the camera shutter. Skaife took several photos that day but this is one of the few that survive. What impressed him however wasn’t so much that he had succeeded in photographing something so completely astonishing as a cannon ball in flight but in every photo that day a face seemed to appear in the smoke. Even stranger, it could only be captured on film, not by the naked eye.

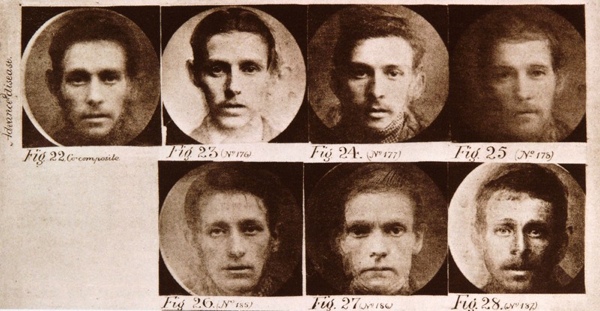

Galton was the cousin of Charles Darwin and he too might have achieved great things in science but his curiosity took him down odd paths. He is credited with the first weather map showing barometric pressure and helped make fingerprinting an essential part of criminology. He also came up with the term ‘eugenics’ and while some think of Galton as a doddering eccentric, others consider him godfather of Nazism. During the 1880s he became obsessed with the notion that races and types had particular facial characteristics and if he could boil those traits down to an essence, so to speak, we would understand so much more about human nature. As part of his experiments he began constructing composite portraits, photographing people as a group and blending the portraits down to a single face. The Director General of Prisons in England, Edmund du Cane, lent him a large batch of portraits of convicts to begin with and he broke those down into murderers, thieves, etc. He also wondered whether there was such a thing as a ‘syphilitic face’, that is, a facial type prone to catching the pox. His work on race is especially notorious. He would go into London’s Jewish quarter in Whitechapel to seek out families but he was convinced the Jewish type was dark-skinned, dark haired and had a large nose. If a family lacked one of those features they were excluded.

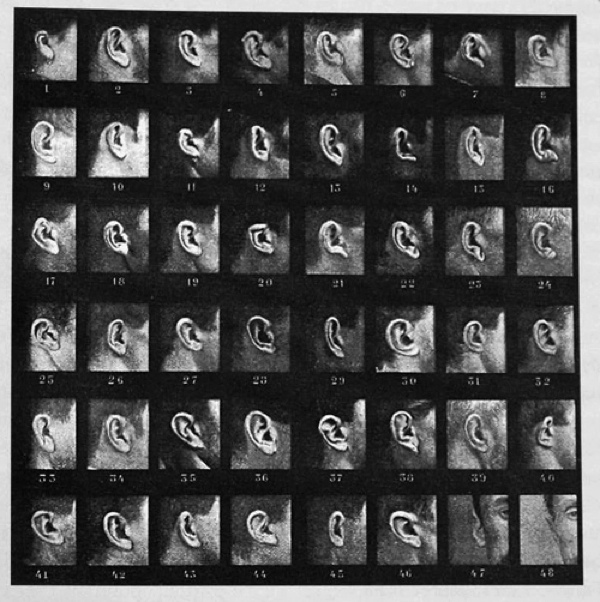

Bertillon is famous for his Bertillon portraits that were used to measure the physical features of criminals and keep them on record. Like Galton he was also interested in genetic characteristics but he wasn’t so concerned with intelligence or personality. Soon after his Bertillon system made him famous, he began to wonder whether there were physical traits unique to French regions. Was there such a thing as the Breton ear, the Norman nose, Alsatian eyes? And if there was, would it be possible eventually to glance at someone and immediately identify his or her genetic heritage? “Ahh, I see one of your grandmothers was Flemish, and you had a Greek ancestor.” To carry out his experiments in the proper way, Bertillon had to photograph thousands of body parts then assume that if a particular feature appeared commonly in one region it must be the prototype. If this sounds like a short road to madness, a lot of French people were inclined to agree. During the trial of Alfred Dreyfus in the 1890s, Bertillon appeared as an expert witness for the prosecution. In order to prove that the handwriting on a document belonged to Dreyfus, Bertillon set up an elaborate apparatus in the courtroom but it took so long to put together that spectators began to jeer and the judge threw him out. His reputation was destroyed after that. John Toohey is the author of Captain Bligh’s Portable Nightmare (probably out of print) and Quiros (Definitely out of print). He is a photo-historian and author of the blog One Man’s Treasure.