Similarities between the two decades do exist, however. One being a sense of transition, as both started amid a global pandemic. So while reflecting back upon the 1920s at this festive time of year, let us remind ourselves that countless brunos, flappers, and moonshiners merrily lifted their glasses of eggnog with no more of a clue than we have today as to what the new year might bring…

10 Santa Hasn’t Aged a Day

If you take a good look at pictures of Christmas celebrations from the 1920s, you might take note of the black-and-white photography, the outdated style of clothing, and the antiquated architecture. But what you might notice with surprise is that Santa looked basically the same as he does today, with his long, white beard, jolly smile, and rounded belly, still dressed in his red cap and coat, both with white trim. Truly, the image of the “jolly old elf” has changed drastically throughout the centuries, as the St. Nicholas of medieval Europe was portrayed to be a thin man in saintly garb. However, the modern version of the portly guy has been fully formed as we know him in the U.S. since the mid-1800s. A hundred years back, he was often referred to as Father Christmas, a separate folkloric entity from England that had culturally merged with the American concept of Santa Claus. For promotional events, Santa (aka St. Nick or Kris Kringle) sometimes arrived via airplane, as if flying in directly from the North Pole. During parades, he was frequently attended to by little, pre-politically correct Eskimos in lieu of elves. The big guy also appeared in many print ads during the ’20s—a good number of them hawking cigarettes or carbonated water, which was in high demand for mixing with Prohibition-era moonshine. As you look through those black-and-white photos mentioned above, you’re liable to come across department store Santas (a la Macy’s) greeting kids in a makeshift “Santaland,” proving that holiday commercialism was certainly alive and well a century back. And while the actors who took such roles were often stereotyped as bums and winos trying to make an easy buck, modern-day professional Santas are raking it in. There are booking agencies that hire Santas to work malls and events during the season all across the country. The average salary is roughly 40 grand a year, with high achievers making significantly more! It’s like when ho-ho-ho meets ka-ching![1]

9 What About Santa’s Crew?

The very first Macy’s Thanksgiving Day parade (called a Christmas Parade) was held in 1924. Starting a long-lasting tradition, Santa Claus arrived last in line on a sleigh pulled by two horses representing reindeer, though it seems he left his little helpers back home at the North Pole [LINK 2]. As you look through old photos of the decade, costumed elves are hard to find despite being prevalent in literature and art. Norman Rockwell’s classic painting Santa with Elves appeared on a cover of The Saturday Evening Post in 1922, wherein he depicted the little guys as being just a few inches tall. That was standard for elfin imagery of the day; it wasn’t until actual people began playing elves in Christmas movies and, later, on TV that our pop-cultural perception of them sprouted to at least the size of a child. By 1920 the concept of a matronly Mrs. Claus had already been deeply ingrained within the ever-growing pool of Christmas lore, right alongside reindeer with names such as Dancer, Prancer, and Donner. But Rudolph the red-nosed wonder wouldn’t join the team until 1939 when he first appeared in a children’s book for a department store in Chicago. And Frosty the Snowman wouldn’t make the roster until 1950, being the subject of a silly song sung by Gene Autry. During the ’20s, the concept of Santa Claus was often referenced with Jack Frost, an impish sprite who brought on frigid weather while nipping at people’s noses. He was the subject of many popular stories and poems, and his wintry presence translated well into Christmas themes.[2]

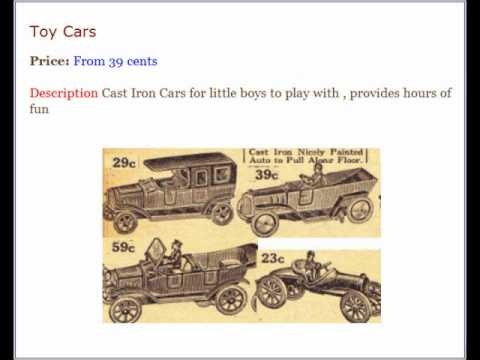

8 The Season of Giving

A hundred years ago, a boy might have written a letter to Santa requesting a sled, a BB gun, a Lionel train set, or a rather novel item at the time called Tinkertoys! In her own letter, a girl might have asked for a doll, doll clothes, a dollhouse, and one of those newfangled, little red wagons to tote all that doll stuff around. Moms who were lucky enough to live in homes with electricity hoped for modern appliances such as vacuum cleaners, toasters, and washing machines. Dads could probably expect practical gifts such as socks, tools, and ties—and a hundred years later, they still can. Fancy wrapping paper, similar to what we use today, was expensive and not for the average household, whose occupants generally wrapped presents in much-cheaper tissue paper. Unfortunately, scotch tape hadn’t yet been invented, so the paper was either bound with string or secured with gummed package seals, some of which contained holiday designs and were thus called “Christmas Seals.” Such gifts were placed around bulky Christmas trees, which were often as wide as they were tall.

7 What the Dickens!

If you looked through cookbooks from the 1920s, you would find recipes for a complete Christmas dinner, with suggestions such as roast duck with plum pudding or roast beef with Yorkshire pudding. The concept of Christmas dinner had become very Dickensian, and increasingly so throughout the decade, as did other aspects of the holiday. The ’20s kicked off on the tail end of the Spanish flu pandemic, which sprung from World War One, and people were ready for more innocent times, which included a Victorian-era type Christmas. Nostalgia for the warmth of the holiday as Dickens portrayed it pervaded both art and design, and sprigs of holly replaced pine boughs across America. Watch this video on YouTube It was a false nostalgia, however. The stereotypical, Victorian-type Christmas had never existed in the United States, and it had only half-existed in England. Yet it had a nice feel to it. Top hats, antique candle holders, and geese became holiday imagery, and celebrants began caroling in groups despite the fact prior to Dickens’s novel, A Christmas Carol, it hadn’t been popular in England for years. Where will our post-pandemic holiday trends take us a hundred years later? Already Americans seem to be putting up their Christmas decorations much earlier than usual and more abundantly, and increasingly Black Friday sales are starting the day after Halloween. Perhaps, here in the almost dystopian 2020s, exorbitance replaces the subtlety of top hats and holly…[4]

6 Holiday Broadcasting

No matter what your favorite television program might be, odds are, most years, it’ll air a special Christmas presentation. Holiday themes seem to be good for ratings, whether it be Peter Griffith’s yuletide hijinks in the town of Quahog, a Brooklyn Nine-Nine caroling contest, or even a Goldbergs’ Hanukkah episode. With streaming services such as Hulu, Apple TV+, and YouTube, along with holiday programming on regular channels, we can watch such timeless classics as It’s a Wonderful Life, Rudolph the Red-Nose Reindeer, and How the Grinch Stole Christmas each year. And it’s not hard to find nonstop holiday programming during the month of December. Watch this video on YouTube But a hundred years ago, there was no television. Instead, families gathered around the radio, often in the evening, for entertainment, and lucky for them popular music had just begun to be publicly broadcast. Holiday selections such as “Adeste Fideles” (by the Associated Glee Clubs of America) and “Parade of the Wooden Soldiers” (performed by three different bands early on in the decade) brought Christmas cheer right into many homes. Holiday parties of the ’20s often gravitated around the sophistication of the radio, and delicious hors d’oeuvres would have been served, such as deviled eggs or fancy sandwiches using that exotic, new food item—Wonder Bread. Eggnog powder was available to be added to milk, and though Prohibition was active, on Christmas Eve, the powder was probably also frequently mixed with rum. And there was always room for Jell-O back in the ’20s, as it was considered to be “the bee’s knees,” most especially the “red flavor” during Christmastime. Throughout the decade, one theme that was broadcast rather often was presentations of A Christmas Carol, with its very first radio reading having aired on December 22, 1922. This is no surprise due to all the Victorian-era holiday nostalgia of the day, which is probably why the tale was cinematically released a total of four times during the decade. That’s an awful lot of plum pudding…[5]

5 Caroling

The radio was not the only option for music in the ’20s. Phonographs, early forms of the record player, were in many homes, but only a handful of Christmas records were available to play. Fortunately, back in the day, popular music was released both on disc and as sheet music, and in the early half of the century, pianos were often more easy to find than phonographs. Throwing a Christmas party with a piano lent a level of sophistication for the guests, who were more than happy to sing together songs like “The Twelve Days of Christmas” while sipping smuggled champagne and snacking on that new and revolutionary delicacy of desserts—the pineapple upside-down cake. People back then enjoyed making their own music, so it was only natural that caroling would become a popular Christmas tradition during the decade. The fact that Dickens mentioned it in A Christmas Carol must have also inspired many merry groups of people to trudge through snowfall, their breaths freezing before them as they sang, even though caroling was almost a lost tradition in England when the book was written in the mid-1800s. And while most of the Christmas songs we have today hadn’t yet been written, popular carols of the day were “Silent Night,” “Jingle Bells,” “The First Noel,” “Hark! The Herald Angels Sing,” and “Auld Lang Syne.” Back then, carolers went door to door, and their holiday visits were warmly welcomed, often reciprocated with warm mugs of hot cocoa or cider… Boy, times have certainly changed. Caroling is a rarity these days, and most Americans have never participated in the activity. Besides, people no longer need to make music to listen to it, especially when it comes to Christmas music. Radio stations offer holiday content 24/7/365, and their selections are often from vastly different genres. In 2014 a search was done on Spotify-Echo Nest to see how many Christmas songs exist, with alternative parameters such as winter and inspirational themes included in the tally. And guess what—914,047 individual tracks popped up, which, after taking into account songs appearing on multiple compilation albums, boils down to 180,660 selections of unique content. That would make for some serious caroling.[6]

4 Fruitcake Humor

Back in the ’20s, there were many delectable desserts served at Christmas, such as butterscotch cake, raisin pie, and, of course, elegant Jell-O molds. And off to one side, there was often a solid brick of fruitcake—untouched, ridiculed, and perhaps regifted. The mass production of fruitcake in the early 1900s, using cheap ingredients and sold in mail-order tin containers, offered a dry imitation of the once rich and delicious dessert. And as for homemade fruitcake, Prohibition took away the key ingredient—whiskey! Many etymologists trace the phrase “nuttier than a fruitcake” to the 1920s, along with other derogatory meanings of the word which sprung from the idiom. Fruitcake humor, in general, seems to have gotten started during the decade, which makes you wonder why, a full hundred years later, we’re still gifting the darn things… The thing about fruitcake is that it doesn’t really have to suck. The British seem to do it right, and it’s a staple at royal weddings. But Americans do not take the dessert seriously at all. Since 1996 the town of Manitou Springs, Colorado, has held a yearly fruitcake toss in January, an event that also collects donations for a local food pantry. And participants of National Fruitcake Day, an unofficial holiday falling on December 27, seem to poke fun at the edible doorstop more so than honor it. Some people even seem unable to say the word “fruitcake” without laughing. The concept of fruitcake humor has been around for a hundred years at this point, and since it doesn’t seem to be going away anytime soon, perhaps we should revisit the Brits’ version of the dessert. Between dried fruit soaked overnight in dark tea, along with the perfect combo of nuts, spices, and fine sherry, the outcome is a confection that no Coloradan, nor any other American, would ever catapult into the horizon.[7]

3 The Ongoing Jesus vs. Santa Arm Wrestling Match

Between bouts of “Happy Holidays” vs. “Merry Christmas” on social media, at the workplace, and often while carving the ham, we think back to a much less politically correct time…perhaps a hundred years ago…and we peacefully smile. Watch this video on YouTube Well, think again! In 1921 the iconic tycoon Henry Ford raised a storm by publicly decrying the secularization of the holiday, using non-religious-themed Christmas cards as an example. His declaration included anti-Semitic statements accusing Jewish department store owners of both profiteering and conspiracy! His words generated widespread political debate. It’s been a hundred years since Henry Ford’s angry rant, but there have been many others since who’ve jumped in the ring. In the past century, we have seen public school pageants canceled, Nativity scenes picketed, and the popularization of the phrase “Keep Christ in Christmas.” We’ve seen SANTA anagrammed into SATAN and Christmas parties renamed “winter celebrations.” Of course, we’ve also all seen headlines about banning Christmas trees in public buildings, First Amendment standoffs, and the highly publicized Kentucky “Charlie Brown” bill. After a full century of seasonal debate, these issues, much like fruitcake humor, are probably not going away anytime soon. But unlike fruitcake humor, Christmas protests from either side can get rather heated and intense, an unfortunate aspect of a holiday that suggests “peace on Earth, goodwill to men.”[8]

2 The Christmas Tree

Christmas trees of the 1920s were rather…well—ugly by today’s standards. They were squat and bulky and sometimes wider than they were tall, which was generally the result of cutting the tops off a pine or a fir. Such trees were decorated with glass ornaments and festive, die-cut cardboard shapes, alongside small toys, snacks, and stringed boxes of animal crackers. Colorful garlands were generously draped upon the tree along with an incredibly flammable, though beautiful, type of tinsel. Putz houses (no joke) were popular nativity scenes or Christmas villages built beneath the tree, often utilizing such items as cardboard, figurines, small toys, and glitter. Artificial trees of German origin made from goose feathers became popular in America during the ’20s, and often the boughs were tipped with red berries that doubled as candle holders. How accommodating… Christmas these days is a lot less combustible, with much safer items such as flame-retardant tinsel being sold to the public. In 2019 more than twice the number of people who bought real trees put up artificial ones, new or previously used. Though most artificial trees are also flame-retardant, there is an increased concern for pre-lit models that run the risk of electrical fires. Back in the ‘20s. the safest thing to do before leaving the room was to blow out the Christmas tree candles, and it seems the safest thing to do today before turning in is to pull the plug.[9]

1 Putting up the Decorations

The average household of the ’20s didn’t put up the tree until right before Christmas and often on Christmas Eve. Stringed lights were expensive in those days, and most people at the turn of the decade didn’t have electricity, so lighting candles on the boughs of the tree, as previously mentioned, was their only option for holiday lights. People were well aware of the risk of fire, so they lit such candles right at Christmas or the night before, and only for a short period, with the tree usually in front of a window for neighbors to see and with a bucket of water nearby in case it burst into flames. Watch this video on YouTube Stockings were actual socks filled with fruit, nuts, candy, and toys that kids would find the morning of Christmas hanging from a doorknob or bedpost. The habit of hanging stockings on the fireplace didn’t happen in the ’20s as, being winter, most fireplaces would have had a roaring fire going to heat the home. The lack of households with electricity and the high cost of Christmas lights kept outdoor decorations humbly unlit. People often decorated their front entrances with green boughs of this and sprigs of that, and a large wreath with a big red bow might have been placed upon the door about the same time the tree went up inside. Outdoor displays were subtle and dignified, often with a Victorian-era slant and always respectful toward neighbors and visitors alike. At least that’s how the decade started… Inspired by a tragic fire in New York City caused by tree candles, the NOMA (National Outfit Manufacturer’s Association) Electric Corporation was formed in the mid-1920s from a trade union specializing in Christmas lights. They offered a safe alternative to candles and, as competition with other companies, lowered the prices. With more and more households acquiring electricity, soon their lights were strung up both indoors and out across America to colorfully brighten the season. Today we seem to put up our holiday decorations earlier each year, and we spend billions in the process. Outdoor Christmas displays have become both complex and competitive, with whole neighborhoods lighting up the night. And often added to these light displays are oversized ornamentation such as waving inflatable snowmen on the lawn, Santa with sleigh and reindeer on the roof, and rows of toy soldiers perhaps lining the drive. You can even deck your house, trees, and entire yard, if you wish, with elaborate pixel lights that flash and shimmer in time to music, and with 180,660 different Christmas songs to choose from, it’s tempting not to keep them up all year round.[10]