Historians and scholars are still uncovering the truth about ancient Greece, and as they do, they are correcting some of the misconceptions that have cropped up around the ancient Greeks and their myths in the last 2,000 years. Here are ten of them.

10 There Was Never A Trojan Horse

The Trojan War was supposed to have taken place during the Bronze Age, when “tens of thousands of Greek warriors” marched on Troy to rescue the captured Helen of Sparta. According to Homer, the Trojan War was started so that Zeus could reduce the human population and so that the king of Sparta could rescue his wife, who had been abducted by the Trojan prince, Paris. The siege of Troy was said to have lasted ten years and finally ended when a huge wooden horse containing Spartan soldiers was left at the gates of Troy, and some fool let it in. That never happened. Since the rediscovery of Troy in modern-day Turkey in the 19th century, archaeologists have uncovered increasing evidence that Troy was already destroyed by the time the war was supposed to have occurred. However, the ruins of Troy would still have been visible at the time Homer wrote the Iliad and perhaps provided inspiration.[1] There is, however, recent evidence that some kind of war may have happened at Troy. Archaeologists have discovered fortifications there which were designed to repel chariot attacks, as well as evidence of destruction at the site. Nevertheless, whatever did happen there is unlikely to have involved any wooden horses.

9 Sparta Was Not Filled With Indomitable Warriors

Although Sparta was a powerful warrior nation for a short time, the popular perception of Spartans as indomitable warriors is inaccurate. The population of Sparta consisted of three main groups: the Spartans themselves, who were full citizens; the Helots, who were slaves; and the Perioeci, who were neither slaves nor citizens but foreigners, visitors, and traders. The Spartans had little interest in the traditional ancient Greek pursuits of poetry and philosophy. They preferred to institute a military system for training their male offspring, separating them from their families from the age of seven and drilling them in warfare. The boys were kept in austere conditions and fed only survival rations. They were expected to learn to steal food to survive. They drilled constantly until, at the age of 20, they became full-time soldiers and remained soldiers until they were allowed to retire at 60, assuming they lived that long. Bravery in battle was expected of all soldiers, and on the eve of war, mothers were said to hand their sons their shields with the words, “Either with this or upon this,” thus exhorting them to either carry their shield home as victors or be carried home dead upon it. The Spartans were not known for being maternal. The Spartans were especially skilled at fighting in a phalanx formation, working side by side with their comrades. However, it seemed to do them little good, and for all their supposed military prowess, the Spartan civilization was a remarkably short one. Sparta suffered a humiliating defeat at the Battle of Leuctra in 371 BC, and the following year, their land was invaded, and the Helot slaves were liberated, marking the beginning of the end of the Spartan nation.[2]

8 Not All Ancient Greeks Were Pederasts

In ancient Greece, it was customary for an adult male to take a young Greek boy as a protege, or eromenos. Formal education did not exist, and in order for a young Greek citizen to progress in society, it was necessary to have a mentor. Some scholars believe that pederastic practices originated in Dorian initiation rites, though there do appear to have been some conventions about the proper way to conduct these relationships. The adult man was to always be the dominant partner, and the relationship was to cease when the eromenos grew a beard, thus signifying his adulthood. Sexual relations between adult men were not considered dignified. Adult men in Greece took citizenship seriously and would enlighten their proteges in all the ways of the world, which sometimes, but not always, included sex. Sexuality in ancient Greece was not considered in terms of relationships but only in terms of desire, or aphrodisia, which might overpower them at any moment. The eromenos was assessed during his period of patronage for his potential to assume civic responsibilities. If the older male refrained from having sex with the eromenos, it was considered to be a mark of respect for the boy’s status, as well as a sign of powerful self-control in the adult, which was good for both of them. However, should the adult lack self-control, the eromenos was expected to comply with any “requests” out of gratitude and respect, as well as the prospect of a lifelong career.[3]

7 They Weren’t All That Democratic

In 507 BC, the Athenian ruler Cleisthenes introduced a new system of “rule by the people,” thus heralding what is often regarded as the birth of democracy. His system comprised three separate institutions: the ekklesia, which wrote laws; the boule, which heard the representatives of the different tribes; and the dikasteria, which formed the judicial system for Greek citizens. Herodotus praised Greek citizens’ “equality before the law.” However, the term “Greek citizens” was interpreted narrowly. Citizenship was conferred only on those whose parents had also been citizens, so this excluded the 10,000 foreigners who resided in Athens, as well as the 150,000 slaves. Of the 100,000 confirmed citizens, only males over the age of 18 were eligible to participate in the new democracy, meaning that only around 40,000 qualified.[4] Although membership of the boule was supposed to be decided by drawing lots, and therefore not susceptible to influence or corruption, historians have discovered that in practice, wealthy people, and their families, were “picked” far more frequently than the odds in a random lottery would suggest. Even the court system was abused. There were no restrictions on the sort of cases that the court could hear, so the citizens of Athens frequently used the court system to arbitrate petty disputes and embarrass their enemies.

6 Hades Was Not Evil

In modern times, Hades is often depicted as a god who, having failed to overthrow Zeus, is banished to the Underworld. Hades is seen as a kind of fallen angel, and the Underworld as a metaphor for Hell.[5] In fact, the Underworld was the place where all human souls go after death. Though parts of the Underworld were considered a place of punishment for sinners, it also included the Elysian Fields, where heroes were bound, and the Asphodel Meadows, where the majority of souls ended up. Hades was, in fact, the ruler of the “invisible world,” and his kingdom included “all the secret places of the world.” He was the brother of Poseidon and Zeus, and the three of them cast lots to divide the world between them. Hades stayed mostly in his Underworld kingdom and rarely bothered those living elsewhere, except, of course, when he abducted Persephone. Having fallen in love with her, he created a beautiful flower that would suck her down to the Underworld when picked. Zeus was forced to negotiate her release, but because of some injudicious pomegranate eating, she was doomed to spend a third of every year in the Underworld with Hades, thus causing winter. Other than that, Hades was a pretty good guy.

5 Pandora Never Opened A Box

In Greek mythology, Pandora was the first woman on Earth. The gods bestowed a number of gifts on Pandora, including the gift of beauty from Aphrodite, music from Apollo, and, somewhat prosaically, clothes from Athena. Zeus, however, gave Pandora a box and told her never to open it, which seems kind of mean. Pandora, of course, opened the box, which turned out to contain all the evils of the world. The evils escaped, and Pandora quickly slammed the lid shut, with only Hope still left at the bottom of the box. However, Pandora never had a box. She had a jar. The jar, or pythos, was the size of a small person and would have been used for storing wine or oil. Such jars were also sometimes used, in place of a coffin, as a burial container. It is believed that the error comes from a mistranslation by the 16th-century writer Erasamus, who mixed up the word pythos with pyxis, which, of course, means “box.”[6] Cool story though.

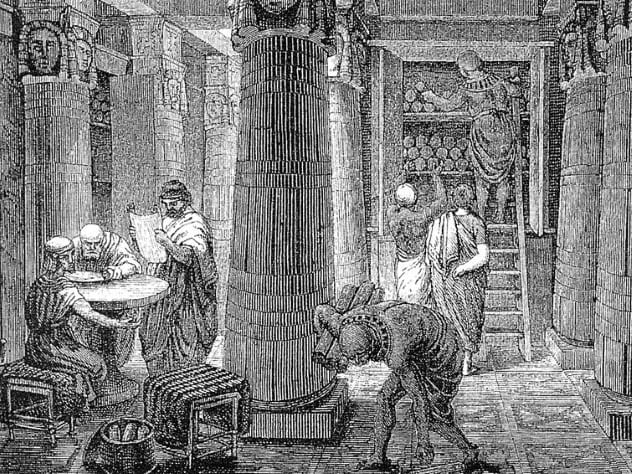

4 The Library At Alexandria Was Not Destroyed By A Muslim Army

The Library at Alexandria was one of the wonders of the ancient world. It contained books and scrolls from ancient civilizations and was a hub for scholars from all over the known world. Alexander the Great was known to be not only a soldier but a scholar. After his death, a great library was eventually built in his honor, to contain all the knowledge of the world. Books and scrolls were brought form all over the known world. Ships that entered the harbor at Alexandria were stripped of their books. The books were taken to the library, where they were copied. The copies were returned to the ships, with the originals being kept in the library. Estimates vary on the number of books the library held, but it is thought to have been anywhere between 40,000 and 400,000 works, a colossal number for ancient times, when all documents were handwritten. The library was filled with scribes, which is ironic, since the fate of the library itself was never properly documented, and many rumors have circulated about the cause of its destruction, including that it was destroyed by an invading Muslim army. It is likely, however, that, far from being destroyed as the result of a single event, the Great Library fell into decay after a number of partial disasters. In 48 BC, Julius Caesar, during a civil war, found himself trapped in Alexandria and set fire to his and his enemies’ ships, burning them and large parts of the town. Some scholars suggest that part of the library may have been destroyed at that time, while others maintain that it remained untouched. It was still in existence in AD 391, when the Roman emperor Theodosius declared paganism illegal and burned down any temple which did not worship Christ, including the Serapeum, where the library was held. It is not known whether the books were inside the building when the torches were lit. However, by the time the Muslim army invaded in AD 641, the library had long been destroyed. Many medieval tales surfaced of how the “infidels” had destroyed the center of learning and civilization, but they were largely fabrication and propaganda. It was known that large collections of books from the Great Library had been traded all over Europe for hundreds of years before the Muslim army arrived. Current scholars tend to favor the theory that the library suffered from a slow decline rather than catastrophic destruction and that its fortune was tied to that of Egypt. As Egypt ceased to be a major power, scholars stopped making the trip to the greatest library in the world.[7]

3 Achilles’s Heel Was Not His Heel

Achilles, the great warrior, was the son of a king and a sea goddess and was raised by a centaur. His birth was preceded by a prophecy that he would be stronger than either Zeus or Poseidon. Consequently, he was a marked man, and in a scenario that sounds like the plot of a Terminator movie, his mother decided to train him to be a fearless warrior. In order to make him immortal, she dipped him in the waters of the River Styx, thereby making his whole body invulnerable, except for the heel by which she had held him. Later, Achilles was killed by being shot in the heel with a poisoned arrow. However, Achilles’s heel was not his actual heel. His Achilles Heel was his pride, and the whole heel thing was actually just a metaphor. Hearing that Achilles had been prophesied to die at Troy, his mother, who was more of a hindrance than a help, commissioned a sword and shield to be made for him by the blacksmith to the gods, Hephaestus, and while they were super-strong, they were also extremely distinctive and marked Achilles out to his enemies. In the Iliad, Homer describes Achilles as proud and vengeful. He led his army into battle against Troy, but when Agamemnon, king of Mycenae and brother of the king of Sparta, gave away Achilles’s wife as part of a peace deal, Achilles refused to fight anymore. Later, he killed Hector (who had killed Patroclus, with whom Achilles was quite close) at the gates of Troy and stabbed him in the throat, denying his pleas that Achilles allow him to be buried inside the gates of Troy. Instead, he was said to have shown his contempt by dragging the body behind his chariot and tossing it on a rubbish heap. Homer does not describe Achilles’s death in the Iliad, but later legends embellished the tale by saying that Hector’s brother, Paris, avenged his death by shooting Achilles in the heel, with Apollo guiding the arrow to the one vulnerable spot on his otherwise invulnerable body.[8]

2 Aphrodite Was Not Always Lovable

Everyone knows that Aphrodite is the goddess of love and sexual desire. Aphrodite was born from the white foam produced by the severed genitals of Uranus, after his son threw them into the sea. Despite this, she was beautiful and was widely worshiped as a goddess of love and fertility, though probably not by Uranus. Aphrodite was said to have had a number of lovers, both mortal and divine, including Ares, the Olympian god of war. Ares, who represents destruction and brutality, was beloved by no one, except Aphrodite. Zeus called Ares “the most hateful of all the gods.” Aphrodite, however, saw something in him and had many children with him, despite being married to his brother, Hephaestus. Hephaestus laid a trap for the two lovers, who were caught in an invisible net which had been laid over her bed. Aphrodite was partly responsible for the outbreak of the Trojan War, offering Paris the most beautiful woman in the world if he named her the most beautiful goddess. He did, and she chose Helen, the queen of Sparta, thus precipitating a ten-year war. Though Aphrodite is usually depicted naked, or nearly naked, she sometimes is shown wearing the armor of Ares. It is said that she wore his armor while he slept and used his highly polished shield as a mirror to admire her beauty. The depiction is also a reminder of her power for good or ill.[9]

1 Eros Was Not A Chubby Baby

Eros was originally said to be the son of Chaos, though later histories said he was the son of Aphrodite and either Zeus, Ares, or maybe Hermes. Eros was the god of passion and fertility and an opponent of his brother, Anteros, who was the god of mutual love. Eros was depicted as a young man, in, shall we say, the prime of life. He was strong, handsome, and athletic. He carried a bow and a quiver full of arrows, some tipped with gold and others with lead. The gold-tipped arrows inspired extreme desire, while the lead-tipped ones produced extreme loathing. One day, angry at being mocked by Apollo, Eros shot him with a golden arrow, forcing him to fall in love with the nymph Daphne. At the same time, he shot her with a lead arrow so that she would find his advances revolting. Awkward. His other targets included Helen of Troy, who fell in love with Paris, causing all that trouble, and Psyche, who Eros bewitched to fall in love with him. He carried Psyche to a secret castle and visited her in the dead of night, refusing to reveal his identity. Psyche fell in love with him, and one night, while he slept beside her, she lit a lantern so that she could see his face, and Eros, on waking, took fright and ran away. Eros was first portrayed as a full-grown man, then a youth, then a child, and finally as a chubby, winged baby shooting indiscriminate arrows of desire,[10] which, considering what he did to Psyche, is a little disturbing.