While fans everywhere mourn the loss, it’s a good time to look back on the fascinating life of this unique visual artist. Here are 10 cool facts about the life of filmmaker and special effects artist extraordinaire Douglas Trumbull.

10 It Runs in the Family

Douglas Trumbull was born on April 8, 1942, in Los Angeles, California. Growing up near Hollywood surely gave him a leg up for eventually breaking into the industry—as did a family connection. Douglas’s father, Don Trumbull, was an aerospace engineer who also happened to work on the special effects for Star Wars (1977) and one of Hollywood’s earliest hits known for its visual effects: The Wizard of Oz (1939). Although the senior Trumbull didn’t have another film credit until after Douglas became successful in the industry, he did later work with his son on films like Close Encounters of the Third Kind and Star Trek: The Motion Picture. It’s clear that the talents that make one a great visual artist run in the Trumbull family. [1]

9 Childhood Electronics and Building

While growing up in California, Trumbull was fascinated with how mechanical and electronic devices work. He even built his own crystal set radios. A crystal set radio is a small device that can not only pick up audio from radio signals but also power itself from the received signals. This kind of aptitude with mechanics and electricity led him to want to pursue a career in architecture. However, his unique talents would lead him in a direction that would allow him to incorporate his other interests of outer space and science fiction films.[2]

8 Films for NASA and the Air Force

Before he could pursue architecture, Trumbull’s illustrations of planets and spaceships caught the attention of Graphic Films, a small animation and graphic arts studio. Graphic Films was a contractor for the U.S. government, specifically NASA and the U.S. Air Force. While employed there, Trumbull would work on documentaries and conceptual films for those agencies. Some of the films were even shot in Cinerama, a very widescreen process requiring three separate projectors to present back on a curved, wraparound movie screen. A precursor to today’s IMAX, Cinerama proved to be an exceptionally good fit for the needs of Graphic Films and NASA in explaining the agency’s future plans for space travel.[3]

7 Ticket to the 1964 World’s Fair

One of the Cinerama productions Trumbull worked on for Graphic Films ended up playing at the 1964 World’s Fair in New York. To the Moon and Beyond played at the Transportation and Travel Pavilion at the fair. The immersive Cinerama presentation promised audiences a realistic idea of space travel, a full five years before NASA put astronauts on the moon. The film’s poster told audiences to be prepared to “be propelled on the most fantastic, incredible voyage through billions of miles of space…from its utmost outer reaches…back to the Earth itself, and into the center of the minutest atom. All through the magic of Cinerama!”[4]

6 A Call to Kubrick

Two important visitors to the 1964 World’s Fair had a keen interest in To the Moon and Beyond. Director Stanley Kubrick and science fiction author Arthur C. Clarke were beginning pre-production work on what would become the landmark 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey. Impressed by the realism of To the Moon and Beyond, Kubrick hired Graphic Films as advisors and storyboard artists for his new film project. Once Kubrick ended his relationship with Graphic Films, Trumbull took a leap of faith and cold-called Kubrick to share his ideas for how Kubrick could realize his vision. This phone call proved to be the pivotal moment in Trumbull’s career, as Kubrick then contacted Trumbull’s boss at Graphic Films and arranged for Trumbull to come to England to work on the film.[5]

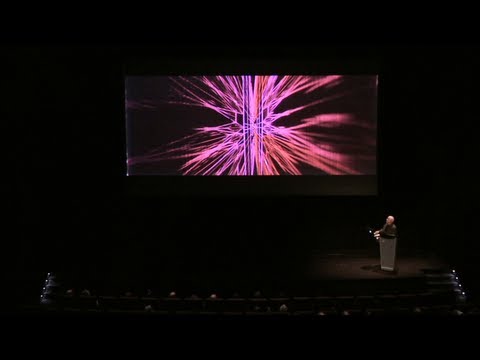

5 A Stargate Is Born

While working on 2001, the production team would eventually figure out how to turn the words on the script into the elaborate special effects the film became legendary for. The famous “Stargate” sequence, when astronaut Dave Bowman (Keir Dullea) first makes contact with alien life, was not terribly well defined when it came time to shoot it. Trumbull recalled that the team had a vague idea about one of Jupiter’s moons that had a tunnel through which another part of the universe could be seen. However, there was no clear plan on how to take the idea from concept to reality. He noted, “It wasn’t my job to create a solution, but I was watching what others were doing, and you could see it just wasn’t working.” After finding inspiration from some “avant-garde animation films he had seen,” Trumbull developed a machine he called a “slit-scan.” The machine “moved colorful artwork behind slits while the camera moved away from the slit.” This is the scene that we see in the film today. Kubrick decided the effects worked the film and told Trumbull to “keep shooting, keep shooting.”[6]

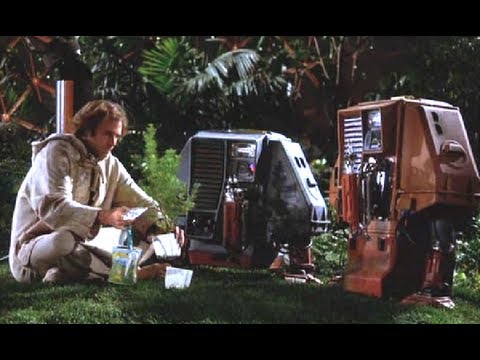

4 The Birth of Familiar Droids

Trumbull parlayed his success from 2001 into more Hollywood special effects jobs and, just a few years later, a chance to direct his own film, Silent Running. The story follows a botanist (Bruce Dern) in the future who has been tasked with keeping plants and animals alive until Earth is safe to inhabit again. He does this with the help of some small robots (designed by Trumbull, naturally). Viewers who have checked out Silent Running only after seeing Star Wars can’t help but notice that the robots in Silent Running wouldn’t feel out of place as droids in the Star Wars universe. Norman Reynolds, the art director for the first Star Wars film from 1977, acknowledges this by saying, “I remember watching Silent Running for the robots.” Some of the similarities between the Silent Running robots and droids that have been noted include retractable arms, the ability to interact with computers, and built-in tools. But perhaps the biggest similarity is the beeps and whistles that the robots in both films use to communicate.[7]

3 Directing the Shots

We mentioned before how, after coming up with how to shoot the 2001 Stargate sequence, he shot much of it himself at the urging of Kubrick. This experience, along with becoming a director in his own right, led other directors who hired Trumbull to allow him to shoot his special effects sequences. Some of his most notable work was in 1979’s Star Trek: The Motion Picture. According to the Hollywood Reporter, director Robert Wise had Trumbull shoot the docking sequence aboard the Enterprise and Spock’s spacewalk. It’s probably no coincidence that these are two of the most highly regarded scenes in this Star Trek classic.[8]

2 A Universal Back to the Future

When Universal Studios wanted to create a Back to the Future ride, they contracted with a company called Berkshire Ridefilm. This is one of several companies that Trumbull started and named after the Berkshire hills area of Massachusetts where he lived. Given his credentials and experience with To the Moon and Beyond and the sense of movement in the 2001 Stargate sequence, he was the ideal candidate to help Universal bring the ride to life. He directed the 4-minute film that’s a part of the ride. Trumbull took on the job with his characteristic zeal and inventiveness, and he can be seen on YouTube talking about how he conveyed the sense of motion that is so key to the ride to the short film.[9]

1 Saving the Planet

The Deepwater Horizon oil spill, also known as the BP oil spill, started within days of the April 20, 2010 explosion and sinking of the Deepwater Horizon oil rig in the Gulf of Mexico. By the time the leak was under control, an estimated 3.19 million barrels of oil had leaked into the Gulf. Ever the inventor, Trumbull took to social media with a solution concept that garnered a lot of attention at the time as a common-sense way to clean up the Gulf waters. His concept and pitch can still be seen on YouTube. In the end, no governments or BP reached out to Trumbull to follow up on the idea, but one does have to wonder if his ideas were incorporated into cleanup efforts.[10]