10 Edwin Davis

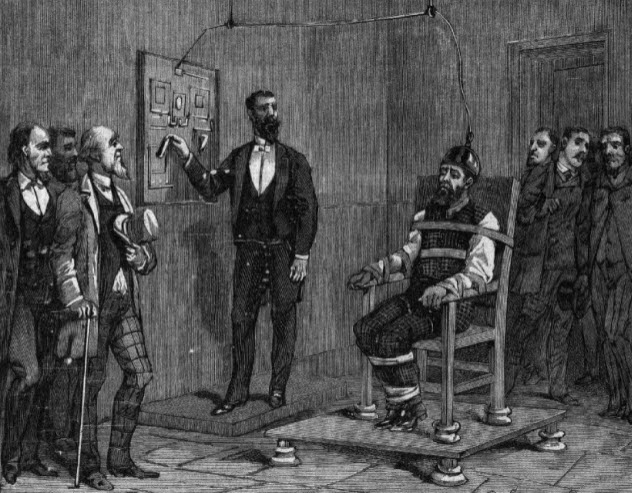

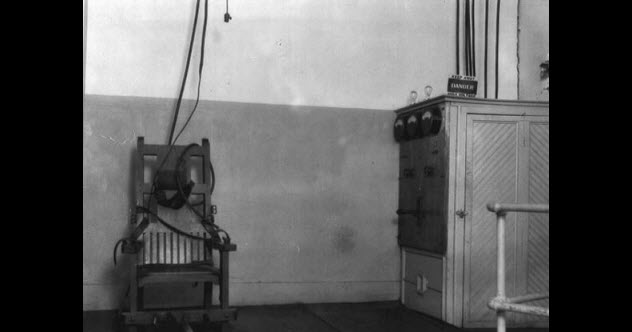

Hanging is grim business. The drop from the gallows is meant to break the neck and make death instantaneous, but it usually doesn’t happen that way. Before succumbing to asphyxiation, the condemned can twist in the air for 10 or 20 minutes—gasping, choking, and wetting themselves. In the late 1800s, the state of New York adopted electrocution to end all that unpleasantness. On August 6, 1890, the first execution in an electric chair took place in New York’s Auburn Prison. Before taking a seat, convicted murderer William Kemmler gave witnesses a ceremonious bow. “I think it is much better to die by electricity than it is by hanging,” he reportedly said. “It will not give me any pain.” Turning to Warden Charles Durston and prison electrician Edwin Davis, he added, “Now take your time, and do it right.” At the signal, Davis pulled the switch, giving the condemned a 17-second shock. However, when the voltage stopped, witnesses saw Kemmler’s chest expand as he struggled to breathe. Davis gave a second zap, reportedly lasting several minutes. Witnesses smelled charred flesh. A news reporter fainted. But when the voltage finally stopped, Kemmler was dead, and the execution was pronounced a success. Davis administered his man-made lightning to more than 300 convicts in several states before retiring in 1914. Among the electrocuted were Martha Place, the first woman in the chair, and Leon Czolgosz, the assassin of President William McKinley. Davis built the first electrocution device himself. Proud of his work, he even applied for a patent and began calling himself “the father of the electric chair.” But that “honor” actually belongs to inventor Thomas Edison. Today, Edison is seen as an avuncular engineering genius, but he was also a ruthless businessman. In the 1880s, he began marketing an electric transmission system based on direct current. At the same time, rival George Westinghouse was pushing a system that used alternating current (AC). In an effort to quash the competition, Edison launched a PR campaign to convince the public that AC was dangerous. He staged a series of bizarre demonstrations in which dogs, cats, barnyard animals, and even an orangutan were given lethal AC jolts. Then he promoted electrocution—with AC—as a humane method for judicial executions. He suggested that prison authorities call it “Westinghousing.”

9 John Hulbert

John W. Hulbert Jr., an Edwin Davis protege, took over as New York’s executioner after his mentor retired. He juiced more than 140 convicts before quitting the post in 1926. “I got tired of killing people,” he reportedly said at his retirement. He received $150 for a night’s work and sometimes as much as $450, a hefty paycheck in that age. But the job may have cost him more than he earned. Hulbert went to great lengths to protect his privacy. He never gave an interview and never allowed the press to obtain a photograph. Nevertheless, news reporters dogged him. As the years passed, the stress of the job affected Hulbert. He carried a gun, fearing he’d be attacked by friends of those who’d sat in his chair. On execution nights, he always dined in the same restaurant, eating the same meal and demanding to be served by the same waiter, who received a generous tip. Why? Because Hulbert feared that someone might poison his food. He once fainted at the switch. Revived by the Sing Sing doctor, he pulled the lever and then spent a week in a hospital. In 1929, three years after he’d quit his job, Hulbert descended into the basement of his house and shot himself. After his passing, one New York newspaper reported that he was never seen shaking hands with anyone.

8 Robert Elliott

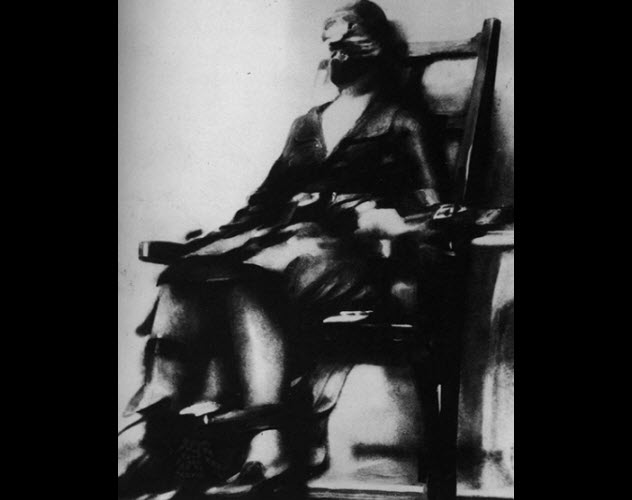

When Robert Elliott first replaced Hulbert as New York’s executioner, Elliott also tried to conceal his identity. Less than a year after his first death chamber job, a reporter followed him from Sing Sing prison to his Queens home, and his name became public. Angry letters filled his mailbox. A short time later, a bomb ripped the front porch off his house. “I would rather shoot the juice into someone than talk to a newspaper,” Elliott reportedly said. Nevertheless, his career was a long one. While employed by New York, he also provided freelance services to about six other northeastern states. From 1926 to 1939, he snuffed out 387 convicts. The condemned included Bruno Hauptmann (convicted of kidnapping and killing Charles Lindbergh’s infant son), Italian immigrants Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti (whom many believe were wrongly executed), and sexy husband-slayer Ruth Snyder and her lover Judd Gray. A witness to Snyder’s execution smuggled a camera into the viewing area by strapping it to his leg. The moment Elliott pulled the switch, the witness raised his trouser leg and snapped an iconic photo, which ran in the Daily News the next day. Unlike Hulbert, Elliott never lost any sleep over his job. He went to church on Sunday mornings, fished in Long Island Sound, played bridge, and raised a flower garden that was the pride of the neighborhood. With his name exposed by the press, Elliott eventually chose to pen a book titled Agent of Death: The Memoirs of an Executioner. In its pages, he revealed his personal opposition to capital punishment. Revenge should be in God’s hands, he maintained, not man’s. He did his job, he said, to ensure that executions were done humanely.

7 Joseph Francel

Joseph Francel, Sing Sing’s executioner from 1939 to 1953, was another prison electrician who shunned publicity. An article in the Nashua Telegraph described him as “a quiet Catskill mountain villager” and “a soft-voiced Cairo traveling salesman.” But the 137 men and women he juiced included some of the most notorious convicts of the age, and that put his name in the public eye. In 1944, he pulled the switch on Louis “Lepke” Buchalter, the country’s biggest labor racketeer and a leader of the mob hit squad “Murder, Inc.” That same night, Francel pulled the switch on two of Lepke’s henchmen, Mendy Weiss and Louis Capone (no relation to Al), as well as two Brooklyn cop killers, Joseph Palmer and Vincent Sallami, making the death chamber that evening’s social center. On June 19, 1953, Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, a married couple convicted of stealing atomic secrets for the Soviets, took turns sitting in Francel’s chair. They claimed innocence to the end. Julius was the first to die, and he went without a hitch. However, Ethel required a second jolt, raising concerns that she may have been killed several minutes into the Jewish Sabbath. Later that same summer, Francel resigned. According to an article in the Milwaukee Sentinel, he told the warden that he had received “too many threats and too little pay.” For the record, he was paid the usual rate—$150 a pop.

6 James Van Hise

In 1907, New Jersey’s first electrocution took place at the state prison in Trenton with Edwin Davis at the switch. For a while longer, the other prisons in the state continued to rely on the services of curmudgeonly hangman James Van Hise. He reportedly hanged 250 people during his career and told reporters that there wasn’t a single atheist in the bunch. According to an article in The Morning Call, Van Hise said, “There was never one that didn’t join the salvation crowd just before the time came to be shuffled off.” Perhaps worried that he might soon be replaced by an electrician, Van Hise sought to improve the gallows to make it more humane. Rather than use the drop to break the neck of the condemned, he proposed attaching a large weight to the rope and letting the weight fall, which would yank the victim into the air. Van Hise was in a grumpy mood the day that he debuted his invention. Convicted wife-killer Edwin Tapley approached the gallows singing a hymn. “Hurry up! Hurry up!” Van Hise snarled, according to an article in the Wangaui Chronicle. The condemned then offered a few last words to express his penitence, but Van Hise cut him off by pulling a black hood over his face. The hangman pulled the lever and sent the prisoner swinging. A doctor examined Tapley seven minutes later and found him still alive. Van Hise put the rope around the prisoner’s neck again and let him hang six minutes more. The doctor then pronounced Tapley dead. “Van Hise was greatly chagrined,” the Wangaui Chronicle reported. He tried to blame the bungling on two ministers, saying they distracted him with their talk while he was affixing the mask and noose.

5 Rich Owens

When a professional executioner from Little Rock showed up too drunk to do the job, prison guard Rich Owens got his first chance to pull the switch on Oklahoma’s electric chair. “I just walked over and slapped it to him like I had been doing it all my life,” Owens later told Ray Parr of the Daily Oklahoman. “Somebody had to pull it as the fellow was already in the chair waiting. I never feel a man should have to wait any longer than he has to.” Between 1918 and 1947, Owens sent volts through 65 convicts. He killed 10 others in his lifetime, was tried for murder four times, and was acquitted each time. He first committed homicide at age 13 when he caught a thief attempting to ride off on his father’s horse. Owens once electrocuted a prisoner who had saved his life by fighting off an attack on Owens by six other inmates. The executioner demanded his $100 bonus the next morning and gave the money to the dead man’s wife. He killed two prisoners who tried to use him as a human shield in an escape attempt. They stuck a knife in his back to prod him forward. When a tower guard shot and wounded one of the pair, Owens grabbed the knife. He stabbed one of the would-be escapees and beat the other to death with a shovel, while the man hollered, “Please don’t kill me, Mr. Rich.” “What kind of a penitentiary would we have here without the chair?” he asked reporter Parr. “It is a pleasure to kill some of these dirty so-and-so’s. Just think what they have done to people.”

4 Jimmy Thompson

Jimmy Thompson, Mississippi’s executioner during the 1940s, had no qualms about discussing his profession. “Colorful” was the adjective news writers often used to describe the heavily tattooed ex–carnival barker. After pumping voltage into wife-killer Willie Mae Bragg, Thompson boasted that the man departed “with tears in his eyes for the efficient care I took to give him a good clean burning.” Mississippi switched from hanging to electrocution in 1940. With hangings, executions took place in the same county in which the condemned man was sentenced. The legislature decided to continue that tradition for electrocutions, so Thompson drove around the state in a new pickup truck with a generator and a sturdy chair outfitted with straps and electrodes. An ex-con himself, Thompson did the job in jail yards, not in public. Nevertheless, crowds gathered outside to see the lights dim. To satisfy folks’ curiosity about his machine, Thompson sometimes gave nonlethal demonstrations. As part of his spiel, he boasted that he gave each victim “the prettiest death a guy can have.” Thompson was paid $100 each time he fed someone the “Big Shock,” $200 for what he called “a double header.” He reportedly went on a drinking binge after each execution. The next morning, he’d kiss goodbye a big chunk of the execution fee to post bail for drunk-and-disorderly charges.

3 T. Berry Bruce

Around the time that Mississippi switched to gas chamber executions in 1955, the executioner’s name became confidential information. However, in the early 1980s, legal papers leaked from the governor’s office revealed that produce salesman T. Berry Bruce had been pumping the gas since 1957. Bruce, a crusty veteran of World War II and the Korean War, killed more than a dozen people before retiring as executioner in 1964. During that time, almost no one knew that he played the Grim Reaper’s errand boy. Even his wife was in the dark. His name was exposed when executions resumed after a 19-year moratorium. Reporters came looking for interviews, and Bruce was accommodating. He told the Southam News that he had no worries about the possibility of wrongful executions. “I feel that’s the court,” he said. “Not me . . . After I gas his ass, I can go out and drink a pint of whisky, and it don’t faze me.” Shortly after that interview, Bruce briefly came out of retirement. However, the 1983 gassing of convicted child rapist and murderer Jimmy Lee Gray was badly bungled, prompting the state to switch to lethal injection. Guards had led Gray into the gas chamber and strapped him into the chair. Bruce then dropped cyanide pellets into a bucket of acid to fill the booth with deadly vapors. But Gray didn’t lapse quietly into unconsciousness as expected. Instead, he gasped for eight minutes and repeatedly banged his head against a metal bar behind the chair. So shocking was the scene that the warden dismissed the witnesses before the victim was pronounced dead. According to some disturbing reports, Bruce was intoxicated when he released the gas.

2 John C. Woods

After hanging 10 top leaders of the Third Reich who had been sentenced to death at the 1946 Nuremberg trials, US Army Master Sergeant John Clarence Woods saw himself as a hero. “I hanged those ten Nazis,” he told Time magazine. “And I am proud of it . . . I wasn’t nervous . . . A fellow can’t afford to have nerves in this business.” Although Woods claimed a much higher body count, some historians estimate that he hanged 60 to 100 men during World War II and for a short time thereafter. Besides hanging those sentenced at Nuremberg, he executed war criminals in Rheinbach, Bruchsal, and Landsberg. He also hanged American servicemen sentenced at court-martials on the European continent. However, controversy followed the Nuremberg hangings. When Third Reich propaganda official Julius Streicher was heard moaning while swinging, Woods stepped behind the curtain that shielded witnesses from the sight of the hanging convict. Most presumed he pulled down on the body to hasten death. Ever since, Nazi apologists have made the claim that Woods deliberately botched the hanging to inflict suffering, although they have no concrete evidence. Woods never had a chance to respond to those allegations. He died four years after the Nuremberg executions, after being accidentally electrocuted while repairing lighting equipment.

1 Jerry Givens

In the era of lethal injection, most prison executioners in the US have remained anonymous. An exception is Jerry Givens, who formerly ran death equipment (for both electrocution and lethal injection) for the state of Virginia. He outed himself by becoming an anti–death penalty crusader. “Biggest mistake I ever made was taking the job as an executioner,” Givens told The Guardian. “Life is short . . . Death is going to come to us. We don’t have to kill one another.” Givens was a prison guard when he agreed to become the state’s executioner. At that time, Virginia had no prisoners on death row because the state had only recently reinstated the death penalty. However, those cells quickly filled up. Givens executed 62 men during his career, by electrocution in the first years and lethal injection in the later ones. He performed his duties for 17 years. Toward the end, he said, he began to suffer flashbacks and mental torment. Although he considered quitting, he was charged with money laundering before that happened. Givens lost his job and served four years in prison, although he insists to this day that he was wrongly convicted. The experience prodded him to speak out. Givens has also focused attention on what psychiatrists are now calling “executioner’s stress,” a type of post-traumatic stress disorder that can afflict guards, wardens, and anyone else who participates in state-sanctioned homicides. “The executioner is the one that suffers,” he told Newsweek. “The person that carries out the execution itself is stuck with it the rest of his life. He has to wear that burden. Who would want that on them?” Joe Arimathea is a professional curmudgeon.