The project was extremely complex and dangerous, even causing the deaths of some of its own scientists. Nevertheless, its story is fascinating, and it is one of the most significant human achievements in the history of our world. Our list today looks at ten interesting facts from the Manhattan Project and the people who helped to make it happen.

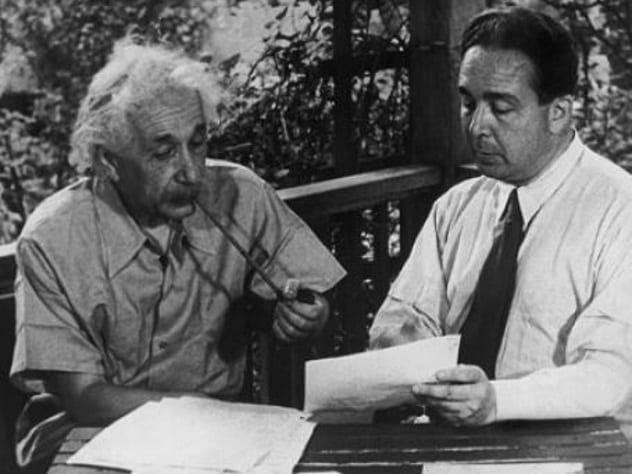

10 Einstein Was Integral To The Project Happening

The history of the Manhattan Project is often told as beginning with the Einstein-Szilard letter. This famous letter, which was signed by Albert Einstein himself in 1939, was mailed to the president of the United States, Franklin D. Roosevelt. The writer of the letter, Leo Szilard, had composed it in conjunction with other prominent physicists Eugene Wigner and Edward Teller, based on the realization that a new power was emerging from the nuclear research of the time. This power, harnessed by heavy atoms, could cause destruction unlike anything the world had seen before, and this was a potentially extremely dangerous position to be in, as Nazi Germany could harness this power. Szilard organized getting the letter composed with Einstein, and it was sent to President Roosevelt. The letter said, “This new phenomenon would also lead to the construction of bombs,” and that this “could be achieved in the immediate future.”[1] The letter also said that Germany had already begun to stockpile sources of uranium from Czechoslovakia, suggesting that the Nazis were already researching the new science. Roosevelt received the letter and decided to take action, creating the Advisory Committee on Uranium. This was the very beginning of the US government supporting research into uranium and would ultimately lead to the Manhattan Project, which started in 1942.

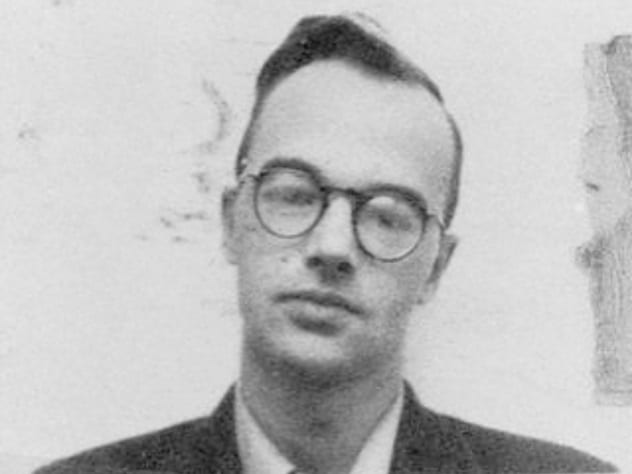

9 The Project Was Infiltrated By Russia

The Manhattan Project was, for obvious reasons, top secret, and intelligence officials and the FBI did everything they could to keep Nazi Germany or Japan from learning about what was happening. Although the USSR were allies of the US, the US still wanted to keep them away from the project and avoid them benefiting from the research and testing being conducted. Despite this, the USSR managed to successfully infiltrate the Manhattan Project. Soviet intelligence had picked up on the fact that British and American publications into nuclear fission had recently dipped—this was a red flag. Reportedly, Soviet spies were foiled at many attempts, but some managed to infiltrate the project and send back critical information—one of the most notable being Klaus Fuchs. Fuchs, a physicist, had secretly sworn allegiance to the USSR, offering his services to them. He had been assigned to the Los Alamos laboratory working on bomb research and design. He would pass on information to the USSR while working in Los Alamos and would be eventually caught after the war, confessing to everything.[2] Other spies remain unknown to this day, and their identities were never uncovered by US counterintelligence.

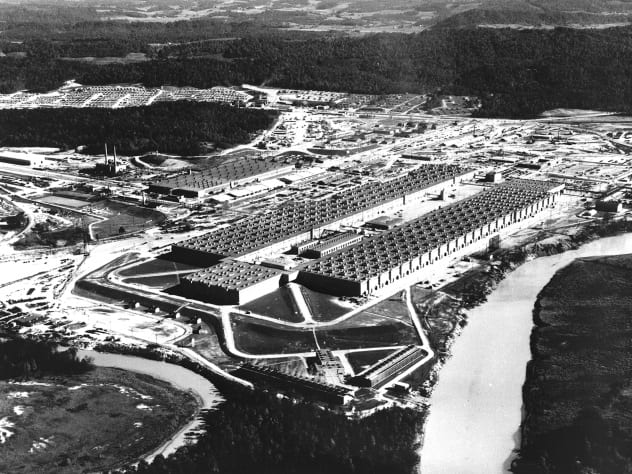

8 The Project Cost Almost $2 Billion

The Manhattan Project was a complex effort, spread out over multiple sites across the US and Canada. The most important sites to the project were Oak Ridge in Tennessee and Los Alamos in New Mexico. Oak Ridge served as the main production plant, which produced the enriched uranium needed to create an atomic bomb. The Los Alamos site was a remotely located laboratory which was tasked with designing and building the bombs.[3] The first-ever detonation of a nuclear bomb in history was achieved in New Mexico, when the Trinity test was performed. Many other sites fed into the project, and because of this, the costs added up. Much of the expense came from the Oak Ridge site. It was estimated that the total project costs were $1.9 billion, which would be well over $20 billion in today’s dollars.

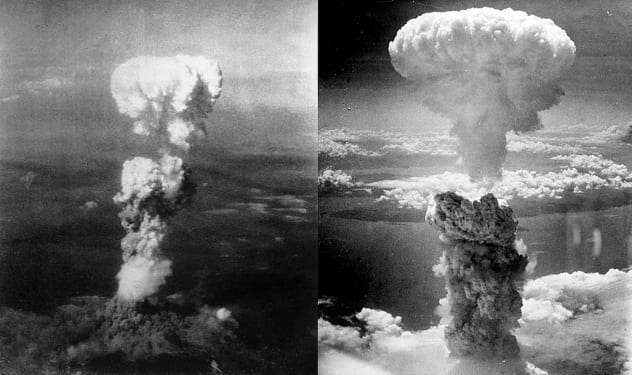

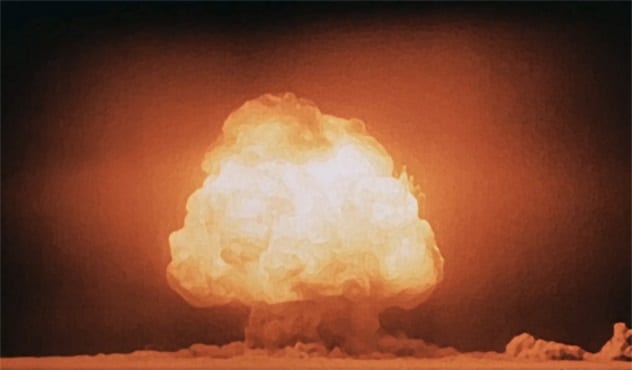

7 The Project Was Deemed A Success

Despite the costs of the project being more than originally budgeted, despite the fatalities during the work, and despite all of the scientific challenges that occurred, the Manhattan Project was deemed a success. The overall objective of the project was to arm the US with an atomic bomb against the Nazi or Japanese threat of doing the same. However, whether the project really was a success is more of an ethical question than a factual one. The project delivered the only two atomic bombs ever detonated in warfare, with the total estimated deaths from those detonations being somewhere between 150,000 and 200,000 people.[4] The bombs ushered in a new nuclear era in which Russia and the US would emerge as superpowers, both armed with nuclear bombs, ready to destroy entire cities instantly. The bombings in Japan in 1945 brought about an abrupt end to the war and potentially saved many US lives, but the bombings today still pose a problematic question as to whether they were truly necessary and if they were morally correct. Some would argue they were a war crime; others would say they were justified and necessary. Without the “success” of the Manhattan Project, who knows who would have been the first country to use a nuclear bomb in World War II?

6 The Demon Core

According to reports, there were 24 fatalities during the Manhattan Project’s lifespan. Many of these were deaths caused by things like construction accidents. However, for scientists Harry Daghlian and Louis Slotin, it was a different case completely. Daghlian was a scientist who was working on experiments using the third nuclear core (with the first and second having been used in Japan). On August 21, 1945, Daghlian accidentally dropped a tungsten carbide brick onto the plutonium core assembly, which made the core go supercritical. He quickly got the brick off the core, but he would receive a lethal dose of radiation because of his accident and died in agony around a month later. Despite this incident, nine months later, Slotin would die from the same core in another fatal accident. On May 21, 1946, Slotin was holding the top part of a beryllium neutron reflector in place above the core assembly with a screwdriver. (A recreation of the procedure is pictured above.) Then, his screwdriver slipped, and the half-sphere fell totally onto the core. This slip caused a lethal amount of radiation to be released in a flash of blue light. Slotin quickly flipped the top part of the reflector off the core and onto the floor, neutralizing the threat. Nevertheless, the he would die from acute radiation poisoning nine days later.[5] The plutonium core was later nicknamed the “Demon Core” because of its involvement in the two scientists’ deaths. It was later melted down, and its material was used in other cores.

5 Thin Man

In the early stages of the Manhattan Project, considerable research and attention was placed on designing a plutonium-based “gun-type” bomb. The work was code-named “Thin Man,” in contrast to the “Fat Man” bomb dropped on Nagasaki. Fat Man worked by plutonium implosion, whereas Thin Man bombs would have worked by having two plutonium masses coming into contact with each other at high speed inside the bomb. Thin Man was ultimately abandoned due to a number of difficulties experienced during research. Firstly, the bombs would have been 5.2 meters (17 ft) long, and this posed a challenge, as finding a suitable aircraft to carry them was difficult. Bombers could be modified to fit the longer casings, but it was later learned that the design of the two plutonium masses made the bombs likely to pre-detonate. Due to this, the casings would have to have been extended, and this put the design outside the realms of what was possible to carry on an airplane of the time.[6] This effectively spelled the end of the project. “Little Boy,” the bomb ultimately dropped on Hiroshima, was a gun-type bomb, but it utilized uranium-235 instead of plutonium-239, as Thin Man bombs would have.

4 The Trinity Test Had Provisions In Case Of Disaster

One of the key milestones of the Manhattan Project was the Trinity test—the first-ever detonation of a nuclear bomb. The test occurred on July 16, 1945, and was conducted by exploding “Gadget,” a device similar to Fat Man. The test was successful and quite literally started the atomic era. Prior to the test, which was top secret, officials were forced to come up with ways to hide it from the public and press, which would prove difficult, considering the enormity of the predicted explosion. A writer for The New York Times, William Laurence, had been drafted into the Manhattan Project for this very reason. Laurence would help put together press releases that would cover up the events. Laurence wrote four press releases for the public attention the test would garner, with the most severe including a blank list of those people killed by the explosion and instructions for evacuation situations. There was considerable worry that this press release would be needed. However, the press release ultimately used hid the event by attributing the noise and heat wave to a “remotely located ammunition magazine containing a considerable amount of high explosives and pyrotechnics” that had exploded.[7]

3 The Project Was Not Based In Manhattan

Despite the name of the Manhattan Project, the bulk of the work conducted during its existence didn’t take place in Manhattan. In fact, as mentioned, the two most prominent sites were in New Mexico and Tennessee. During the project’s beginning, its official name was “Development of Substitute Materials,” but this never really stuck. President Roosevelt had assigned the project to the Army, and General Leslie R. Groves took up residence in Manhattan initially to draw on the nearby Corps of Engineers division.[8] Later, it was agreed that “Development of Substitute Materials” may have been too obvious, so they settled for “Manhattan District.” As the project expanded, and the need for multiple sites and laboratories became evident, the Army began to move away from Manhattan. However, the name followed them. Later on, the “District” part was used less and less until the project was known simply as the “Manhattan Project.”

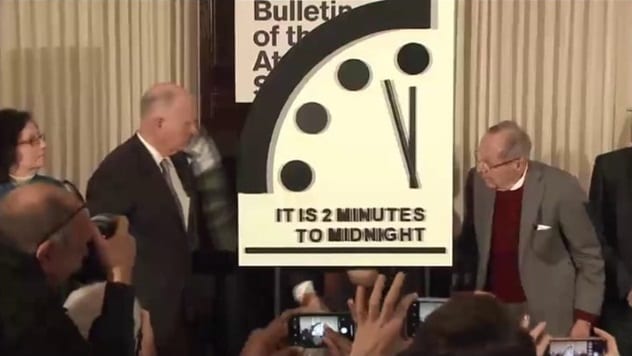

2 The Doomsday Clock Was Born Out Of The Manhattan Project

After the closure of the Manhattan Project, many scientists were left ruminating about the overall impact the nuclear bomb would have in the future of the Earth. After the bombings of Nagasaki and Hiroshima, it’s not hard to see why. Therefore, in 1945, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists was created, and it began to publish monthly informational pieces about the developments and dangers of the newly dubbed “Atomic era.”[9] One of the founders of the Bulletin was a biophysicist named Eugene Rabinowitch, who had worked on the Manhattan Project during World War II. Rabinowitch said that the aim of the Bulletin was to “awaken the public to the full understanding of the horrendous reality of nuclear weapons and of their far-reaching implications for the future of mankind.” In 1947, the Bulletin started to produce the Doomsday Clock, a way of measuring how close humanity was to destroying the world with man-made nuclear weapons. When the first Doomsday Clock was released, the time was 11:53 PM (seven minutes to midnight). The furthest away the clock has been from midnight was in 1991, at the end of the Cold War between Russia and the US. The clock is presently at two minutes to midnight, the worst it has ever been, due to current concerning international stances of countries.

1 The Project Is Still Referenced In Popular Culture Today

The Manhattan Project has certainly not been forgotten more than 70 years after its completion. It is still referenced in many popular culture genres, essentially paving the way for an entirely new subgenre of nuclear destruction. The Manhattan Project has been featured in many television shows, movies, documentaries, pieces of fiction, music, art, and other forms of pop culture such as video gaming and board games. Quickly following the close of the project, the film The Beginning or the End was released in 1947, which depicted an inaccurate and villainous story of how the atomic bombs were made.[10] Many years later, the TV movie Day One provided a much more accurate portrayal of the project, going on to win an Emmy Award for Outstanding Drama. More recently, the Manhattan Project has been referenced in the Marvel Cinematic Universe in Iron Man, where the central character Tony Stark makes reference to his father helping the Manhattan Project. Other portrayals include books such as Los Alamos by Joseph Kanon and The Wives of Los Alamos by Tarashea Nesbit. In 2014, a television series simply named Manhattan was produced for two seasons to critical acclaim before its cancellation in 2016. There have been and will continue to be many depictions of the project, as over 70 years later, we still find ourselves fascinated by the work conducted during the Manhattan Project.