Ancient hunter-gathers used ivory for tools as well as their most sacred objects. Since then, countless other cultures have carved ivory into items both decorative and utilitarian. The demand for this precious substance is so great that many ivory-producing animals have been hunted to near-extinction. Today, the world struggles to find a replacement for this beautiful, useful, and utterly unsustainable resource.

10 Ivory Rope Maker

In August 2015, archaeologists discovered a 40,000-year-old, ivory rope-making tool in a cave in southwestern Germany. Initially believed to be a flute or shaft straightener, the mammoth tusk tool is 20 centimeters (8 in) long and contains four holes, each bearing deep spiral incisions. This was not for decoration. It was cutting-edge Stone Age technology. The spirals guided plant fibers as they were twisted into rope. Hohle Fels Cave, where the tool was found, has yielded a treasure trove of well-preserved Paleolithic tools and art. Rope was essential for mobile hunter-gather populations. For decades, the Paleolithic rope-making process remained a mystery. Rope and twine quickly decomposed and left no trace in the archaeological record other than extremely rare cases when they became embedded in fired clay. German researchers have been able to demonstrate how individual plants fibers were passed through the holes to create tough rope fibers.

9 Illyrian Ivory Tablets

In 1979, an Albanian archaeologist discovered five 1,800-year-old ivory tablets during excavations of Durres. Fatos Tartari found the wax-coated tablets within a glass urn, which was also filled with two styluses, an ebony comb, and black liquid. The urn was in an aristocratic woman’s tomb. The unknown liquid preserved the ivory tablets. Otherwise, wax typically detaches and disintegrates as soon as it loses moisture. A team of German and Albanian scientists have recently deciphered the inscriptions, which shed light on the former Roman colony of Dyrrachium in the second century AD. The records indicate that women played a prominent role in ancient Illyrian culture. The tablets indicate that the woman buried in the tomb worked as a moneylender. One record indicates that she was owed a debt of 20,000 denarii—10 times the annual wage of Roman soldiers. According to ancient historians, Illyrian women fought alongside men and held political power.

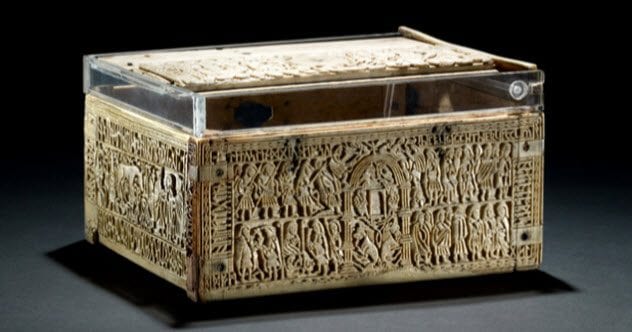

8 Franks Casket

The Franks Casket is an Anglo-Saxon whale’s bone box that reflects a curious melding of Christian, Jewish, and German traditions. Dated to the early eighth century, the ivory artifact contains scenes of the Adoration of the Magi alongside the Germanic tale of Weland’s Exile. The lid depicts the Germanic hero Egil while the underside contains an image of Rome’s capture of Jerusalem in AD 70. Commentaries are inscribed in runic alphabet, Old English, and Latin. At 23 centimeters (9 in) long, 19 centimeters (7 in) wide, and 11 centimeters (4 in) high, the ivory box likely held holy texts. Some speculate that it served as a reliquary for the cult of St. Julian at Brioude. An account in 1291 refers to the Lord of Mercoeur visiting Brioude and “devoutly kissing an ivory box filled with relics.” In the early 19th century, a family in Auzon, France, owned the casket and used it as a sewing box.

7 40,000-Year-Old Animal Figure

In 2013, archaeologists were able to reattach the head to a 40,000-year-old ivory lion sculpture. Discovered in Vogelherd Cave in 1931, the cat’s body was reunited with its head, which was found on an expedition to the same site between 2005 and 2012. It was initially believed to be a relief. Then the discovery of the head revealed that it was clearly a three-dimensional representation of the ancient predator. Vogelherd Cave is located in southwestern Germany’s Lone Valley. Covering over 170 square meters (1,830 ft2), the cave has yielded over two dozen figurines going back to the dawn of Homo sapiens in Europe. In addition to lions, ivory figures have been discovered representing mammoths, camels, and horses. These are considered some of “the oldest and most impressive” Ice Age artwork as well as milestones in human’s emerging cultural innovation. Bone dumps suggest that the cave was used to process and butcher game for millennia.

6 Greenland Walrus Ivory

Archaeologists believe that an ancient “gold rush” prompted the Viking settlement of Greenland. However, they were not in search of precious metal. Their goal was to obtain walrus tusks. In the 11th century, Europe’s interest in ivory exploded. The economy was driven by a desire for luxury goods, and the Vikings were quick to profit off Europe’s thirst for tusks. Walrus ivory was fashioned into jewelry, religious icons, and luxury items for nobility. Between the 12th and 14th centuries, the Viking economy switched from bulk goods—like wool, fish, and timber—to high-end items like ivory. The mystery of why the Vikings decided to settle in Greenland, whose climate is too harsh for agriculture, may finally have been solved. Medieval Iceland also had a walrus population. However, it was probably not enough to sustain European’s ivory addiction. On the other hand, Greenland could. Researchers are currently analyzing isotopes in walrus ivory to determine its origin.

5 Venus Of Brassempouy

In 1892, archaeologists unearthed an enigmatic ivory figurine during excavations of Brassempouy in southwestern France. Dated around 23,000 BC, the “Venus of Brassempouy” contains the earliest-known detailed representation of a human face. She has eyes, brows, a forehead, and a nose. However, she lacks a mouth. Her face contains a vertical crack, but it is probably a flaw in the ivory. It is uncertain whether her hair is in braids or covered with a headdress. Only the head and neck of the Venus was found in Grotte du Pape (“Pope’s Cave”). The Venus of Brassempouy is one of the finest examples of Gravettian art. It was constructed around the same time as other female figurines like the Czech Republic’s Venus of Dolni Vestonice and Italy’s Venus of Savignano. This culture of ancient Venus figurines stretches well into modern-day Russia, as far as the shores of Siberia’s Lake Baikal.

4 Dorset Polar Bear Effigies

The Dorset people were a mysterious group of hunter-gathers that roamed the Canadian Arctic between 500 BC and AD 1000. Named after Cape Dorset, where their artifacts were first discovered, the Dorset were master ivory carvers. Their most frequent subject was the polar bear. Hundreds of ivory Dorset bear carvings have been recovered from Greenland and Northern Canada. Some experts believe that the bears are posed in seal-hunting stances. Others suggest that certain carvings, like the “flying bear” effigies, reflect Dorset spiritual beliefs. Soon after the Inuit encroached on their territory, the Dorset disappeared, leaving only their enigmatic artifacts to speak for them. According to Inuit lore, the Dorset—or “Tuniit”—were giants capable of single-handedly crushing a walrus’ neck and dragging the animal home. However, they were gentle giants who kept to themselves. Art objects appear far more frequently than tools like harpoon heads and knives. Often, even Dorset utility items are decorative.

3 Athena Parthenos

In 438 BC, Athenian statesman Pericles commissioned master sculptor Pheidias to build the Athena Parthenos in honor of the city’s patron deity. At 11.5 meters (37.7 ft) tall, the statue was massive. Its construction was known as chryselephantine—composed of 1,140 kilograms (2,500 lb) of gold and brilliant white ivory for the goddess’ flesh. Additional glass, copper, silver, and jewels adorned the figure. Historians believe that the statue cost roughly 5,000 talents, which was more than the construction cost of the Parthenon where it was housed. The statue would remain Athens’ greatest symbol for a millennium. In Late Antiquity, the Athena Parthenos vanished from the historical record. Some speculate that it was carried to Constantinople, where it was likely destroyed. However, copies exist. The most notable is the Varvakeion statuette from the second century AD. Along with descriptions of the original by ancient historians Plutarch and Pausanias, experts are fairly certain what the original Athena Parthenos looked like.

2 Venus In Furs

In 1957, archaeologists discovered mysterious female figurines carved from mammoth tusk in Buret, Siberia. Dubbed “Venus in Furs,” these enigmatic ivory artifacts were not Venuses at all. Microscopic inspection revealed that some were men and others were children. Experts now believe that the figurines represent real people from 20,000 years ago. Dressed for the Siberian winter, “Venus in Furs” figurines are the oldest representation of sewn clothing in the world. Analysis of the statues revealed various hairstyles, shoes, and accessories. The “Venus in Furs” figurines are remarkably similar to figurines found in Mal’ta, which is about 25 kilometers (15 mi) away. So far, 40 mammoth tusk figurines have been found at both sites in the vicinity of Lake Baikal. Little more than half have undergone microscopic analysis. Further investigation may yield new and unexpected revelations. Many details like bracelets, hats, shoes, and bags have been dulled by time and are not visible to the naked eye.

1 Lewis Chessmen

In 1831, 78 mysterious ivory chess pieces were discovered on Lewis beach in the Hebrides. Found with the buckle of the bag that once carried them, the Lewis chessmen are one of the most cherished Scottish archaeological treasures and the world’s most famous chess pieces. Amounting to 1.4 kilograms (3 lb) of ivory, the find contained nearly four full sets. Only one knight, four rooks, and 44 pawns are missing. Aside from the simple octagonal pawns, each piece is filled with quirks. The queens look aghast or agonized. The stout kings are comically stoic. The rooks bite their shields in battle fury. The ungainly knights look absurd atop their small ponies. Bishops’ eyes bulge from moon faces. Experts believe that the walrus tusk and whale tooth pieces were fashioned in Norway around the late 12th century. No one is certain who carved the Lewis chessmen or how they wound up in the Hebrides. Dubbed the “Indiana Jones of folk music” by TimeOut.com, Geordie McElroy is the leading authority on occult music. He has hunted spell songs, incantations, and arcane melodies for the Smithsonian, Sony Music Group, and private collectors. He is also the singer of LA-based band Blackwater Jukebox.