Musical instruments fall out of favor, noisemaking artifacts are misunderstood, animals go extinct before we know what they sounded like, and sometimes, world-famous musicians’ lost works have never been heard by anyone alive today. Thankfully, researchers are finding ways to revive sound and gain a better understanding about ancient nations, the natural world, and different musical eras.

10 Bronze Age Mouthpiece

While workers worldwide amuse themselves playing with the office 3-D printer, one Australian student used it to revive Bronze Age music. Billy O Foghlu suspected that a bronze artifact called the conical spear butt of Navan wasn’t part of a weapon at all. O Foghlu had something more musical in mind. He believed that mouthpieces for blow horns had once existed in Ireland even though none had been found. The knowledge that such instruments played an integral role in ancient cultures made him doubt the prevailing view that Irish Bronze Age horns were unsophisticated. Just because no mouthpieces had ever been discovered didn’t mean they weren’t used. Somehow, his gut told him that the “spear piece” was the elusive proof. When he couldn’t use the original piece, he simply used its exact measurements and printed a 3-D replica. Then he tested it on his own ancient Irish horn. To his delight, the instrument produced richer sounds and allowed for better control. It also would have allowed ancient musicians a more comfortable way to play these horns and perhaps even broadened their range.

9 Earliest Polyphonic Music

Polyphonic music simply refers to a composition in which two or more independent melodies are played together. The earliest example ever found, a chant dating back to around the year 900, had defied identification ever since it was catalogued in the 18th century. With the composition held at the British Library in London, nobody could make sense of the unusual symbols. That is until Giovanni Varelli came along. An early musical notation specialist, Varelli realized what he was holding in his hands and it shocked him. The piece was so old that it was written before the invention of the stave and broke all the rules of polyphony. This makes the discovery all the more remarkable as it allowed researchers to look at the birth of the music form, and they weren’t seeing what they expected. Polyphony set the rules for most European music until around the 20th century, and those guidelines were fixed and the practice nearly mechanical. However, the unknown author who had penned the chant showed that despite what polyphony later became, its conception was marked by continuous change and experimentation that followed almost none of the rules—as they were being written.

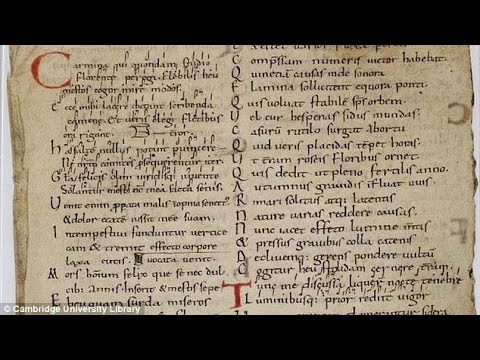

8 Lost Medieval Music

It took 20 years, but for the first time in almost a millennium, we can now listen to what medieval music truly sounded like. Researchers at the University of Cambridge painstakingly attempted to recreate a collection of tunes called the Songs of Consolation, but what held them back was centuries of dead traditions. During the Middle Ages, medieval musicians recorded their songs with melodic outlines and symbols called neumes rather than the notes used today. They taught their students through sound demonstration and memory. None of this helped modern researchers to understand what medieval pitches were like. Without that knowledge, a revival from this era was thought to be impossible. The breakthrough occurred when Cambridge University Library recovered a stolen page from one of its 11th-century manuscripts, the so-called Cambridge Songs. The lost page contained critical information about the era’s musical rules without which the ancient melodies might have remained lost indefinitely.

7 Sound Of Death

It must have looked like a scene from a jungle adventure movie—an Aztec temple containing a skeleton clutching a whistle in each long-dead hand. The whistles were made from clay and shaped to resemble human skulls. For some reason, nobody put their lips to one for 15 years. Perhaps they were understandably creeped out by the morbid-looking artifacts. It could also be because for years, whenever archaeologists found ancient noisemakers, they tended to file them away as toys. Whatever the reason, somebody finally gave it some thought and blew into one of the so-called “whistles of death.” The reedy sound was seriously eerie. Although it has been rather easy to hear an Aztec noisemaker ever since it was created in pre-Columbian times, discovering its purpose will not be so easy. Theories include sacrificial victims playing the whistles before they were packed off to the gods, help for the dead to travel to the underworld, crowd-control whistles, and perhaps even a way to help introduce trances for medical procedures.

6 Jurassic Cricket

A tiny musical fossil has given scientists a rare glimpse into what Jurassic nights sounded like. They were able to bridge the 165-million-year silence after a complete prehistoric cricket, Archaboilus musicus, was discovered and the microscopic structures on its wings were examined. The surprise came when the fossil showed that crickets already produced clear chirps, a trait thought only to have developed much later as a startle reflex. Like modern bush crickets, their extinct cousin also combed one wing over the other using a scissorlike movement to serenade females. But what exactly did they sound like? After studying the Jurassic insect’s anatomy and comparing it to the music organs of living species, it was discovered that A. musicus sent out a pure note with a low pitch. The song, which comes nearest to that of the modern bush cricket, was capable of efficiently transmitting itself through thick vegetation and night noise. Researchers view this as a valuable recovery of what they know about the ecology of the forest during that time. Due to the way the cricket sounded, it suggests that the Jurassic forest flourished with plants and nightlife.

5 Lost Lituus

In the 18th century, Johann Sebastian Bach wrote a choral piece for a musical instrument called the lituus. However, nobody today could appreciate the work as it was meant to be performed originally. The main element was missing. The trumpetlike lituus had been forgotten for as long as 300 years, wiping from memory its sound and, even worse, what it really looked like. Watch this video on YouTube Researchers from the University of Edinburgh used a novel technique not really meant for resurrecting extinct musical instruments, but it worked. First, they compiled data from similar ancient instruments and expert theories on how the lituus was played, how it produced sound, and the quality of its notes. Then they fed the data into a software program initially developed to make modern brass instruments better. The result was incredible. The software came up with something that could have easily been made in Bach’s time, a good indication that the instrument’s design was on the right track or even correct. A physical reconstruction produced a straight horn, 2.5 meters (8.5 ft) long, and with the classic flared tip of a trumpet. Attempting to play the lituus was a clumsy affair but only because of its size and a lack of skillful handling. When researchers learned to play it properly, the haunting trumpeting revived Bach’s music in a way that modern instruments couldn’t match. To hear the instrument, skip to about 05:50 in the video clip above.

4 Unusual Handel

The German-born composer George Frideric Handel penned an unusual piece in 1707. For some reason, no record of it was made anywhere and it ended up being forgotten. Nobody even knew that Handel had written anything of this nature until a German professor from Hamburg University found it while riffling through the library of the Royal Academy of Music in London. The work, “Gloria in Excelsis Deo,” is uncommon because it was written for a solo soprano. During its time, all other “Gloria” settings were only sung by choirs. Handel, who was the favorite composer of the British Royal Family, evidently designed a masterpiece meant to be sung only by the most elite sopranos. Even today, only a few sopranos can sing the complicated but beautiful “Gloria” well. What makes this difficult and rare piece of music even more remarkable is that Handel was only 21 years old when he composed it. “Gloria in Excelsis Deo” was heard again for the first time at the Gottingen International Handel Festival in 2000.

3 The Vivaldi Manuscripts

In 2010, Scotland turned up a surprise find—a long-lost flute concerto by the 18th-century Italian composer Antonio Lucio Vivaldi. Previously, the only proof that it existed was a reference in the sale catalogue of a Dutch bookseller who lived during the same time. It was rediscovered by chance when a researcher at the National Archives of Scotland was going through an old noble family’s papers. The work, “Il Gran Mogol,” proved to be incomplete in two ways. The famous classical composer had written it as part of a quartet of concertos, but to this day, nobody has found the missing three. Also, “Il Gran Mogol” itself was missing a part for the second violin. Luckily, researchers knew of another Vivaldi flute concerto that appeared to be a revision of “Il Gran Mogol.” They borrowed a snippet from the revised manuscript—the part for the lost violin—and the concerto was patched up perfectly. Earlier in 2004, another rare Vivaldi turned up. This time, it was in the vaults of an English castle where the only known copies of the Vivaldi opera La costanza trionfante degl’amori e degl’odii were identified. Both the opera and the flute concerto made their modern debut in recent years.

2 The Mozart-Salieri Score

One popular view of history tells that Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was poisoned by a jealous rival. This angle was even used in the Academy Award–winning movie Amadeus. The supposed perpetrator was composer Antonio Salieri, and while they were certainly competitive, historians have long believed that Salieri’s hand had been nowhere near the poison shop. Now there is some definite proof that they might even have been friends. A Mozart score that was lost for two centuries turned up in a Czech museum in 2015. It had been coauthored not only by Salieri but by a third, unknown composer named Cornetti. It had remained unidentified for so long because the composers had been named in code, which was only recently deciphered. Although some experts don’t see it as Mozart’s greatest work, it is invaluable in other ways. It sheds light on Mozart and Salieri’s famous rivalry and provides a new understanding into Mozart as an opera composer. The four-minute piece was performed on a harpsichord in Prague a year after its discovery.

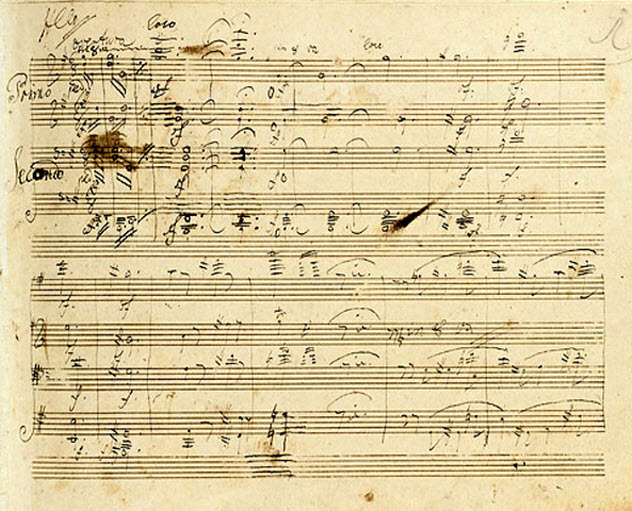

1 The Handwritten Grosse Fuge

One of the most priceless discoveries in music happened because a librarian decided to clean some shelves. It was a unique work written in Beethoven’s own hand when he was already stricken with deafness. The historic discovery is the only one of its kind—a rare piano version of Beethoven’s Grosse Fuge, which has almost mythical status among musicologists. What makes the 80-page manuscript so valuable is that it includes the composer’s own attempts at editing. Unlike Mozart who could pour a nearly complete score on paper the first time, Beethoven was obsessively critical of his own work and never satisfied. The self-editing shows that Beethoven was brutal about perfection. In some places, his impatient cross-outs and adaptations have torn the paper. In an intense fever to produce, Beethoven wiped away wet ink, pasted over sections, and incorrectly spaced notes and even the staves. The handwriting is also agitated. The intense devotion to the piano version could be because the original Grosse Fuge, written for a string quartet, was poorly received by the public. It gives an unprecedented look into the way that Beethoven thought, made decisions, and worked as a composer. The most human touch was numbers to signify the fingering. This suggests that despite being deaf, Beethoven actually played the music on a piano himself. Read More: Facebook Smashwords HubPages