The government of Singapore launched the Speak Mandarin Campaign in 1979 to promote, as the name implies, the speaking of Mandarin amongst Chinese Singaporeans. This policy has come under heavy criticism, especially since the majority of Chinese Singaporeans are from southern China, where mostly non-Mandarin Chinese languages are spoken. As part of the campaign, the government banned non-Mandarin Chinese languages in local broadcast media, and foreign media in those languages is limited. The campaign has met with some success, and has resulted in the increased usage of Mandarin and a decreased usage of the other Chinese languages, which has frequently caused problems in communication between the younger and older generations.

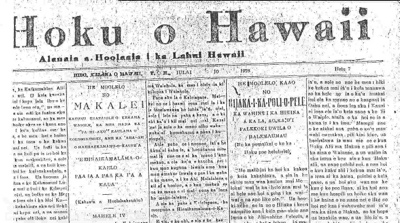

The decline of the Hawaiian language started around the 1820’s, due to the influence of missionaries on the islands. The missionaries’ presence resulted in an increasing number of Hawaiians learning English, but at the expense of Hawaiian. Deliberate attacks on the language didn’t come until 1893, when the Provisional Government, put in place after the fall of the monarchy, attempted to assert the English language’s dominance over Hawaiian. This included the banning of Hawaiian in public schools in 1896 (although Hawaiian was not prohibited in other contexts), which continued well into the 20th century. Hawaiian’s secondary status can still be felt there today: there are only 2,000 native speakers, although efforts to promote the learning and teaching of Hawaiian are proving somewhat successful.

The decline of the Ryukyuan languages started when the Ry?ky? Kingdom lost its independence to Japan, in the late 19th century. The languages were severely suppressed in education by the Japanese government. In Okinawa and other regions of Japan, students were punished for speaking anything other than Standard Japanese, by wearing a “dialect card” around their neck. From World War II up to the present day, Japan has considered the Ryukyuan languages to have the degraded status of a “dialect” of Japanese, rather than a separate language. Today, efforts are made to preserve the languages, but the outlook is less than positive as the vast majority of Okinawan children are now monolingual Japanese speakers.

Korea was occupied by Japan from 1910 to 1945, and during that time suffered from a cultural genocide, which included the repression of the Korean language. In schools, Japanese was the language of instruction while Korean was offered merely as an elective, but, later on, this changed to an outright ban on Korean during school hours. Korean was also banned in the workplace. As part of their cultural assimilation policy, Japan introduced a system in which Koreans could “voluntarily” give up their Korean names, and in their stead take a Japanese one, but many were frequently compelled or harassed into adopting a Japanese name against their will. The colonization ended with Japan’s surrender in World War II, but it continues to cast a shadow over the relationship between the countries.

“Russification” refers to the policies of both Imperial Russia and the Soviet Union to enforce the adoption of the Russian language. It was frequently used by Russian governments to impose their authority on the minorities they governed, often in order to quell separatism and the threat of rebellion. Particularly in the Ukraine and Finland, Russification was used as a means of asserting political domination. One of the most prominent instances of Russification was in the 19th century when Ukrainian, Polish, Lithuanian, and Belarusian were suppressed. Use of the local languages in public places or schools was banned, and these policies intensified after several uprisings occurred. Under the Soviet Union, the Arabic alphabet was eradicated and many languages were ultimately made to adopt variations of the Cyrillic alphabet. In the early years of the USSR, minority languages were actually promoted, but this soon changed to a policy of Russian dominance over local languages. The result was that many people came to prefer Russian over their native language, and today Russian is still widely used in former Soviet states.

England’s domination over Wales, Scotland and Ireland introduced the English language to these regions, but with the devastating consequence of the downfall of the local languages. Welsh, Scottish Gaelic, Scots and Irish (among others) were all prohibited in education at one time or another, which possibly contributed the most to the plummeting usage of the languages. In Wales, the Welsh Not (a piece of wood with the carved letters “WN” that was hung around the children’s necks) was used in the 1800’s to punish students for speaking Welsh, and beating students for using non-English languages was common throughout all of the countries. Welsh, Scots Gaelic and Irish had inferior status to English, whereas Scots wasn’t even recognized as a separate language, and all suffered as a result. It wasn’t until the 20th century that the British government started taking steps to protect these languages, which has been met with mixed success. In all of the countries the local languages are now spoken by a minority, and are still very much secondary to English.

“La vergonha” (Occitan for “the shame”) refers to the policies of the French government regarding the treatment of minority languages in France. The speakers were frequently made to feel excluded or humiliated in school, society, or the media simply for speaking their language. In the late 18th century, all non-French languages were banned in the administration and education, with the goal of “linguistically uniting” France. In the late 19th century, there was the widespread implementation of punishment in schools for speaking the regional languages. Students caught speaking a “patois,” as the French government referred to them to convey a sense of backwardness, were made to wear an object around their neck called a symbole. Discrimination against non-French languages continues to the present day, and remains a taboo topic. Current French president, Nicolas Sarkozy, has, in recent years, refused to ratify the European Charter for Regional or Minority languages, a treaty that aims to protect and promote regional languages.

Indonesia’s ethnically Chinese population faced severe discrimination under President Suharto, who ruled Indonesia from 1967 until his resignation in 1998. Included in this was the harsh suppression of the Chinese languages, which were banned in nearly all aspects of life. All Chinese-language papers were forced to close, except one, and all Chinese-language schools were shut. Chinese script was banned in public, and the police could openly abuse anyone found using the language. Even their names weren’t safe from this cultural genocide, as they were forced to change them to more Indonesian-sounding ones. The severity of Suharto’s policies, combined with the social stigma associated with being Chinese, was unfortunately effective, as many people of the younger generations lost the language of their parents. Following Suharto’s resignation, these bans on the Chinese languages were revoked by President Abdurrahman Wahid.

Under Franco’s rule from 1939 to 1975, regional and minority languages in Spain were discriminated against, to assert the dominance of the Spanish language. Franco’s use of language politics was mainly to promote nationalism, and so Spanish was made the sole official language of the country. The public use of any other language was either banned or frowned upon, depending on the region and time period, and anything other than Spanish names were forbidden. The harshest policies emerged at the beginning of Franco’s rule, in the 1940s and ‘50s, while they became comparatively tolerant in the last years of his regime. To further establish the lower status of the languages, they were often considered to be mere dialects of Spanish, implying that they weren’t real languages (this didn’t apply to Basque, which is far too different from Spanish). The largest of these regional languages were Basque, Catalan and Galician, although all languages were subjected to Franco’s policies. Catalan provides a good example of these laws: it was banned in government-run institutions and public events, advertising, and the media, but it was still used in some contexts. Publishing in Catalan continued throughout Franco’s dictatorship, and there was no prohibition on speaking it in public or in commerce. From the 1950s it was allowed in theater, and near the end of the regime certain celebrations in Catalan were tolerated.

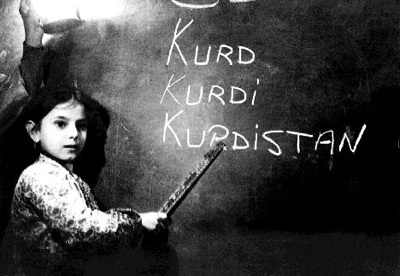

The Kurds have frequently been discriminated against, in multiple countries, and even when the Kurdish people are not the target of genocide, their language still is. Iraq is notable for being perhaps the most accepting of its Kurdish population; it is an official language there, and has been allowed in education, administration and the media. This is, unfortunately, not always true in other countries. Turkey attempted to assimilate non-Turkish speakers, starting in the 1930s, when Kurdish language and culture was banned. The Kurds were seen as uncivilized and ignorant, and any expression of a separate identity was seen as a crime. This finally changed in 1991, when Turkey legalized the private use of spoken Kurdish. Since then, the restrictions have been becoming more and more relaxed: Kurdish in education is no longer illegal, and there are fewer limitations on television broadcasts. Discrimination against the language still very much exists in the country, despite the recent improvements. Something similar happened in Iran, where the government had a policy of “Persianization” in the first half of the 20th century. Speaking Kurdish was banned in schools and state institutions, and later, a total ban on the language was imposed. In other countries, this is still true: in Syria, Kurdish is banned in most contexts.