But that’s not all. New discoveries also updated a mysterious civilization, gave an odd clue to the purpose of the Nazca Lines, and revealed Alcatraz’s military secret.

10 First Napoleonic General

Around 200 years ago, Charles Etienne Gudin was hit by a cannonball. Medical records described damage to both legs, with the left being amputated below the knee. Gudin was a Frenchman. He was also the childhood friend and favorite general of Napoleon Bonaparte. His death was just one of many after the French tried and failed to invade Russia in 1812. Archaeologists found Napoleon’s battered general in 2019 while excavating under a dance floor in Russia. Located in a city 400 kilometers (250 mi) west of Moscow, the coffin held a skeleton missing his left leg. The right leg showed injuries that mirrored Gudin’s final battlefield records.[1] The team also found signs that the man had been both an aristocrat and a military veteran. In that regard, Gudin also fit the bill. If the remains produce a match with the DNA of his living descendants, Gudin would become the first general rediscovered from the Napoleonic period.

9 An Original Schiele

When an art dealer contacted expert Jane Kallir in 2018 and claimed to have found an original Schiele in a Queens thrift shop, Kallir felt no excitement. Nearly all rediscovered art by Egon Schiele is fake. The artist churned out 300 paintings and around 3,000 sketches. When the 28-year-old died from the Spanish flu, he was one of Austria’s leading Expressionists. However, the art dealer had included photos and Kallir found them promising. She managed to get the pencil sketch to New York and examined it up close. She recognized Schiele’s choice of paper and pencil—and nudes. The image showed a naked girl drawn at a difficult angle that only a few people, like Schiele, could manage. The model was recognized as a lady who frequently posed for the artist. Kallir became certain that this was among his last works from 1918 when he died. It seemed to fit with a 22-piece collection, two of which were likely painted on the same day as the newly discovered drawing. The new Schiele is worth $100,000–$200,000.[2]

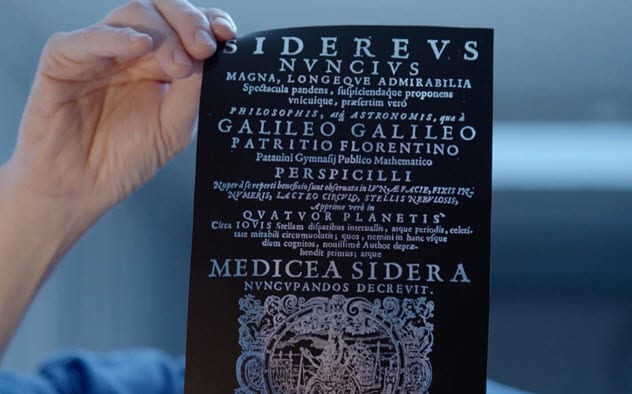

8 The Fake Galileo Book

In 1610, Galileo Galilei published a book that changed the universe. Until then, people thought the Earth was the center of the cosmos. The book effectively argued otherwise and cemented Galileo’s place as an elite astronomer. Called Sidereus Nuncius, only 550 were hand-printed and 150 survive today. In 2005, stunned experts authenticated a unique Sidereus Nuncius. Unlike the rest, it included watercolors done by Galileo himself. Apparently, the work was a proof run of the later book. Things fell apart when its source became known. The man who appeared with the book was Marino Massimo De Caro. He was a known book thief. Scholars reviewed the “proof” and found that its Lincean Academy seal was faked. Galileo had been a member there, but it was confusing as to why somebody would fake a seal when the manuscript already carried the astronomer’s signature. It led to the discovery that both the signature and the book were superb forgeries. De Caro admitted that he had faked four more copies, and their whereabouts remain unknown.[3]

7 A Large Palace

Near the Tigris River in Iraqi Kurdistan, a modern reservoir contained ruins. Archaeologists have known about it for years, but the reservoir’s water made excavations impossible. In 2018, drought peeled back the curtain and a sensational grand palace surfaced. Brand-new cultures are exciting, but finding large structures of civilizations we know little about is more valuable. The floor slabs and rare painted walls belonged to the Mittani Empire. This Bronze Age nation dominated northern Mesopotamia and Syria between 1500 BC and 1300 BC. Historians are also aware that Egyptian pharaohs treated Mittani royals as their equals. However, their day-to-day culture remains elusive.[4] The site yielded a trove of clay tablets. Translation suggested that the palace belonged to the city of Zakhiku, which flourished for 400 years starting around 1800 BC. Experts are still prying meaning from the tablets and hope they will throw light on Mittani politics, economy, and history.

6 Rembrandt’s Unexpected Ingredient

Plumbonacrite is a lead carbonate mineral. Artists from the 20th century onward used it to make paint. Once, it was found as far back as 1889 in Vincent van Gogh’s work. However, nobody expected to find the compound in art from the early 1600s. In 2019, this surprising discovery happened when scientists tried to find out what Rembrandt van Rijn, a Dutch Old Master, used to create his thick paints. Rembrandt was known for his impasto technique, using bulky layers to provide his paintings with a three-dimensional feel. After subjecting three of his best works to X-rays, the plumbonacrite was as clear as day. This ingredient can now be added to other compounds the master used, including linseed oil and lead white pigment. He likely added the plumbonacrite by lacing oils with litharge or lead oxide.[5]

5 The Pigs Of Stonehenge

During Stonehenge’s construction, the builders lived at nearby Durrington Walls. The barracks were excavated for decades. But in 2018, new ceramic fragments and animal bones led researchers to believe that the workers dined mostly on cooked pork. A third of the pottery showed signs of pig fat—and a lot of it. Other researchers did not agree. The pots were large but incapable of holding an unbutchered pig. Most bones at Durrington belonged to whole animals. Burn marks suggested that the pigs were roasted whole over a fire. Undoubtedly, the meat was consumed, but the 2019 study concluded that the vessels collected the fat dripping from the spit. Interestingly, the lard was probably a construction tool used to move Stonehenge’s massive stones into place. During a previous study, archaeologists proved it was possible. In 2018, 10 people moved a greased 1-ton stone at almost 1.6 kilometers per hour (1 mph).[6]

4 Female Viking Warrior Was Slavic

Scandinavian researcher Leszek Gardela studied female Viking warriors. He found several likely instances, and one of them was the well-publicized case of the female Viking warrior buried in Denmark. When her gender was discovered, it caused a stir. No other grave in the cemetery contained weapons, while hers contained a 10th-century coin and an axe. The latter kept showing up in tombs of women with links to the fighting forces of their time. Soon, she was touted as proof that Viking women could also be warriors.[7] In 2019, Gardela had another look at the woman’s axe and it could change her story once again. The 1,000-year-old artifact was distinctly Slavic. So was the grave—a chamber tomb with a coffin. Gardela believed that the woman was not a Viking. Instead, she came from the southern Baltic, possibly modern-day Poland. Additionally, Slavic warriors were present in Denmark at the time. The island where she was buried saw many of their people during the Middle Ages.

3 Foreign Birds At Nazca

The Nazca Lines remain enigmatic. Nobody knows why pre-Inca civilizations “drew” the enormous animals, shapes, and plants from the 4th to 10th centuries AD. In 2019, Japanese researchers focused on the bird geoglyphs. Their expertise in ornithology suggested that several of the species had been misidentified. One of Nazca’s most iconic images is the hummingbird. Only it is not a true hummingbird. The creature is a hermit, a subgroup of hummingbird. Two other birds—previously classified as a coastal guano bird and just “a bird,” respectively—were both recognized by the 2019 study as pelicans. Although the team used exhaustive reference points in anatomy and scientific drawings, they could not fully identify the other 13 avian glyphs. A few of them supposedly showed non-native species. The three reclassified birds were definitely not local. The researchers believed that exotic species were included at Nazca for an important reason and could be key to unraveling the mysterious purpose of the lines.[8]

2 Identity Of Da Vinci’s Mother

The Renaissance artist Leonardo da Vinci was raised by his father Ser Piero da Vinci, a prominent lawyer. Ser Piero was not married to the obscure mother of his child. Most historians agreed that her name was likely Caterina. Since the name was common among slaves at the time, some felt that she was a slave from North Africa or Turkey. In 2017, Martin Kemp, a Leonardo expert, riffled through overlooked documents kept at Florence and Vinci in Italy. Kemp believed that Caterina was a local girl. The archives revealed a destitute orphan, Caterina di Meo Lippi, who lived near Vinci. In July 1451, Ser Piero visited the area. Kemp found evidence that the 15-year-old Caterina gave birth to his child on April 15, 1452. Using property tax records, he also found links suggesting that the da Vinci family gave her a dowry so that she could marry someone else and that Ser Piero later helped Caterina’s husband with a legal matter.[9]

1 The Alcatraz Tunnels

The famous Alcatraz prison stands on an island near San Francisco. It was not always a place for offenders. It was also a lighthouse station and military fortification. In 2019, researchers boarded the island to study its pre-prison history. They did not imagine spectacular results. After all, the island was relatively tiny and could not hide much construction. To prevent costly and damaging excavations, the team used radar and laser to see inside the earth. Remarkably, the scans revealed tunnels and structures from the 1860s. The subterranean works—including bombproof sections, rooms, vaulted tunnels, and air ducts—belonged to Alcatraz’s military era.[10] The relics were superbly preserved, and in some places, they were mere inches from the surface. The fort was built to protect San Francisco from invasion. Over time, it completely disappeared. Finding its complex architecture is a boost for those piecing together the complete history of Alcatraz. Read More: Facebook Smashwords HubPages