But not always. Sometimes, critics come up with theories about classic novels that are a little . . . different. These theories are so outlandish that even if you disagree with them, they’ll forever change the way you see your favorite books.

10Mr. Darcy Got His Fortune From Slavery

Depending on whom you ask, Pride and Prejudice is either the greatest novel ever written, or the 19th-century equivalent of trashy chick lit. The one thing everyone can agree on is that Mr. Darcy is the ultimate romantic hero: a dashing, brooding hunk who just happens to be both unbelievably rich and unexplainably attracted to the protagonist. Yet Darcy may be hiding a secret darker than his admirers would like to admit. It’s been theorized that his wealth comes directly from the slave trade. There are only a few realistic avenues where Darcy’s annual income of £10,000 could come from. The most likely are the sugar trade and mining, two professions that relied on exploitation and horrendous working conditions. According to novelist Joanna Trollope, it’s historically likely that Darcy would’ve been connected to the Caribbean sugar plantations, so he either implicitly or explicitly supported slavery. If the theory seems tenuous, at least one other Austen work supports it. Mansfield Park’s wealthy Sir Thomas Bertram is depicted as an ashamed plantation owner, and several distinguished modern critics have claimed Austen was a passionate abolitionist.

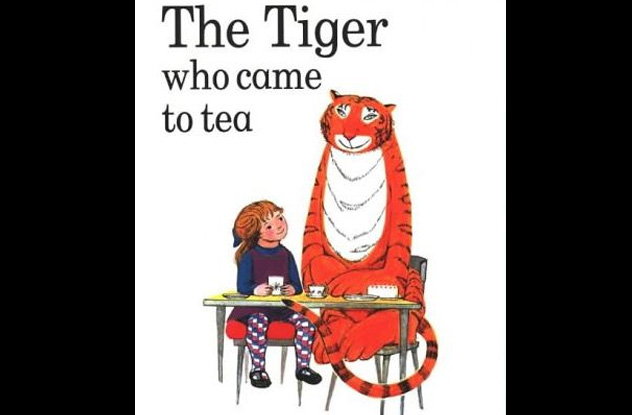

9The Tiger Who Came To Tea Is About The Holocaust

Written by Judith Kerr in 1968, The Tiger Who Came to Tea is a best-selling children’s story about a tiger who (surprise!) comes round a little girl’s house for tea. While there, he eats all the food, drinks all the water, and draws on the walls. It’s an empowerment tale for kids, who get a kick out of watching the tiger do stuff they’d be grounded for. Unless one controversial theory is right, in which case it’s actually about the Holocaust. The daughter of Jewish intellectuals, Judith Kerr grew up in pre–World War II Berlin, an experience that shaped her outlook. In 1932, her father was put on a Gestapo death list, and in 1933, his books were burned at a public gathering. After the family fled to Britain, both her parents were issued suicide pills in case Nazi agents ever tracked them down. It was such a powerful experience that Kerr later wrote a book about it. According to children’s author Michael Rosen, it may even have influenced her most famous work. Rosen claims that the tiger symbolizes the Gestapo—men who had the right to enter Jewish homes and do whatever the hell they liked. In his words, the tiger is “a jokey tiger, but he is a tiger,” a symbol of danger. However, his theory was dealt a major blow when Kerr herself publicly rejected it.

8Frankenstein Is About Pregnancy And Childbirth

A powerful tale of science, morality, and reanimated corpses, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is still popular today. It’s generally read as a parable for man’s dangerous quest for knowledge and irresponsibility for his actions. But there’s a small chance it actually has a more earthbound meaning. It’s been suggested that Frankenstein is really a metaphor for childbirth. In 1814, 16-year-old Mary Shelley eloped with her husband Percy. Eight months later, she suffered a horrendous miscarriage, losing her baby daughter. In 1815, she wrote the following journal entry: “Dream that my little baby came to life again; that it had only been cold, and that we rubbed it before the fire, and it lives.” As horror fans will know, that passage echoes Frankenstein’s pivotal creation scene in a creepily close way. Consider also the words Shelley used to describe her monster’s birth. The word “labor” is used repeatedly, and other sections refer to the “incredible days and nights of labor and fatigue” necessary for Frankenstein to create life. The monster’s development even mimics that of a human child. Unlike the groaning beast of the films, Shelley’s version learns to speak and act like a man by observing other people. Finally, the monster’s first victims are young children, one of whom has the exact name of Shelley’s dead son.

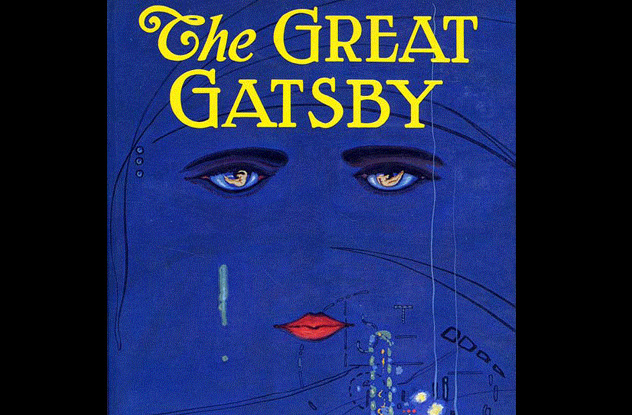

7Jay Gatsby Was Secretly Black

F. Scott Fitzgerald’s brutal demolition of the American dream, The Great Gatsby tells the story of a party animal multimillionaire harboring a dark secret. Although the text is pretty vague, it’s generally understood that Gatsby was born poor and made his money through bootlegging. Not everyone agrees. According to one theory, the secret is Jay Gatsby was born black. The theory claims Fitzgerald crammed his novel with hidden signifiers that Gatsby is passing as white. The book specifically mentions his brown body, and one scene involves a character being rude about him, only to be told forcefully, “We’re all white here.” Gatsby associates himself with New Orleans and jazz music, two bywords for being black in 1920s America. The theory’s advocates pick up on some weirder stuff, too. At one point, readers learn Gatsby has 40 acres, allegedly corresponding to the “40 acres and a mule” freed slaves were traditionally given. It’s even been claimed that Gatsby’s wartime service in Montenegro is significant because the name translates as “Black Mountain.”

6On The Road Is Catholic Propaganda

With its jazz, drugs, cool cars, and casual sex, most people now consider Jack Kerouac’s On the Road to be the bible of the beat generation. Still others see it as a celebration of America, a novel about male sexuality, or an exploration of blue collar values. Very few would call it a religious novel. Yet a school of thought says it’s one of the most openly Catholic books ever written. The interpretation comes directly from Kerouac himself. Raised in a highly Catholic family, Kerouac later claimed his religion influenced everything he wrote. At one point, he even described On the Road as “really a story about two Catholic buddies roaming the country in search of God.” Another time, he claimed all he ever wrote about was Jesus. Even the term “beat” has been linked with religion. Rather than being about music, Kerouac frequently used it as a contraction of “beatitude” or “beatific.” Additionally, the character of Dean Moriarty (based on Neal Cassady) may represent Christ. Far from being a slice of counterculture cool, On the Road may well be about one man’s religious journey.

5Don Quixote Is About Jewish Mysticism

The first modern novel, Cervantes’s Don Quixote tells of a deranged knight who fights windmills, has spectacular misadventures, and generally makes an ass of himself. It’s a straightforward enough comic story but one on which people have hung some strange theories. Chief among them being that the Quixote is stuffed with allusions to Jewish mysticism. The theory comes on the back of the linked theory that Cervantes’s ancestors were Jews forced to go undercover to remain in Spain. Cervantes then included reference to this in his most famous novel, along with several Jewish themes. Supporters of this theory claim the name Quixote is derived from the Aramaic word qeshot (certainty or truth), a word that often appears in Kabbalistic texts. They also point to Don Quixote’s desire to live out life exactly as it is dictated to him by books, a trait that chimes with the challenges of Orthodox Judaism. Structurally, Cervantes’s novel is similar to the Sefer ha-Zohar, a cornerstone of Jewish mysticism. It’s thought that Don Quixote was meant to deliberately echo the Zohar, although others think this was merely a coincidence.

4Babar The Elephant Is About The Joys Of Colonialism

A French children’s character from 1931, Babar is a wild elephant who sees his mother get shot, escapes to the city, and learns to act like a human. He then returns to the wild and winds up becoming king of the elephants, because that’s the sort of feel-good tale we’re dealing with. Unless its left-wing critics are right, in which case it’s an apologist tract for the horrors of colonialism. Among those to argue the case are Chilean writer Ariel Dorfman, who claimed Babar is a colonialist allegory “as seen by the complacent colonizers.” The elephants represent the savage natives of Africa who become human on contact with French civilization. After Babar gets to the city, he starts walking upright and wearing clothes. When he returns to the wild, he quickly dominates the other elephants and forces them to act French, too. In Dorfman’s view, the entire series of books is about subconsciously justifying France’s right to dominate native cultures. Others agree that the books are about colonialism but think Dorfman is missing the point. According to them, Babar is a satire on the very ideas Dorfman accuses it of celebrating.

3Harry Potter Is Doomed To Immortality

Crazy Harry Potter theories are practically an Internet cottage industry. Anything with so many devoted followers is bound to spawn endless speculation, so J.K. Rowling’s series has been enthusiastically interpreted in every way possible. Not every theory is easily dismissible, though. Some, like the immortal Potter theory, even give the books an extra edge. The theory comes from a line about Harry and Voldemort’s destiny: “Either must die at the hand of the other for neither can live while the other survives.” In the books and film, this is interpreted to mean the two characters will be forced into an epic showdown. But some fans have since theorized it meant only Harry and Voldemort were capable of killing one another. With Voldemort dead at the end of the seventh book, this now means Harry has no means of dying. He’s become immortal. In the Potter universe, that’s a pretty big deal. Ghosts exist, as does the chance at an afterlife surrounded by your loved ones. If Harry can’t ever die, he can’t ever join his friends in the next world. They’ll grow old and expire while he carries on living in increasing loneliness. It makes his killing Voldemort the ultimate act of sacrifice, a rather more adult ending than the happy version we really got.

2At The Mountains Of Madness Is About Country Versus City Living

First published in 1936, At the Mountains of Madness concerns the discovery of an ancient alien city in the heart of Antarctica. Widely considered to be one of H.P. Lovecraft’s creepiest tales, it’s an exercise in paranoia and stark alien horror. It may also have a subtext not even the biggest Lovecraft-nerd would know about. It’s been suggested the novella is about the dangers of city living. In 1927, Lovecraft read and fell in love with The Decline of the West by Oswald Spengler. Central to that book is the idea that human civilizations collapse and become degenerate when everyone is concentrated in giant cities. In hysterical passages, Spengler repeatedly denounces the “unnatural” structure of cities. Lovecraft echoes these passages in his description of the aliens’ home. When the scientists reach the alien city, it’s described as made up of angles and shapes unknown to human geometry. Like Spengler’s “vampiric” cities, it’s sucked the world around it dry, leaving only a wasteland and causing the civilization that built it to collapse. There’s even a moment when two characters encounter some old drawings that seem to retell Decline of the West with added space monsters. There are so many parallels in the two books that Lovecraft scholar S.T. Joshi considers it central to understanding Lovecraft’s views.

1Jane Austen’s Novels Are All About Game Theory

At its most basic, game theory is about assessing the choices available to two or more people and giving a value to the benefit they can expect from each choice. While benefit often comes at the expense of other people, game theory shows there’s usually a choice with unexpected benefits for everyone involved. The clever part is mapping how you can steer people toward making a choice that benefits you by making sure it’s in their best interests to choose it. According to one expert, Austen’s characters do this often enough to qualify her as a game theory expert. In Pride and Prejudice, Mrs. Bennett calculates the best time to send her unmarried daughter to the estate of an eligible bachelor is when a storm is brewing. As a result, her daughter gets trapped at the bachelor’s estate overnight, resulting in a blooming romance. In Mansfield Park, Fanny Price needs to get a knife with sentimental value back from her thieving five-year-old sister. She calculates that the kid is more interested in the knife as an object than for its sentimental value, so she buys her a new one and succeeds in getting her knife back. According to UCLA’s Michael Suk-Young Chwe, this is such a perfect example of game theory he uses it as a teaching aid. Go looking, and you’ll find over 50 similar examples in Austen’s six novels. They’re not just high-class versions of Harlequin: They’re game theory textbooks.