But sometimes, the entropy of decay gives way to something breathtaking. Whether at the hand of man or by the slow creep of nature’s tenacious grip, some ruins end up in a surreal twilight between ash and phoenix, poised for something greater than anyone could have imagined.

10Kolmanskop

The story of Kolmanskop begins, as so many African tragedies do, with a diamond. In 1908, German settlers were trying to build a railway across the Namib Desert to connect the coast with the Namibian town of Keetmanshoop. One of the workers, Zacharius Lewala, stumbled across a rough diamond in the desert sands, and he brought it to his supervisor. News of the find spread like wildfire across the German colonies, and miners were soon pouring into the desert by the hundreds. Diamonds on the surface are rare, but legend has it that in Kolmanskop you could walk the desert at night and pick the glittering stones off the sand by moonlight. A makeshift city was built right on the windswept dunes, and at the height of its boom, there were over 1,200 people living in Kolmanskop. Times change, however, and with the combination of dropping diamond prices following World War I and the discovery of more diamonds farther south, Kolmanskop’s popularity dwindled. Miners and their families packed their bags, abandoned their homes, and left the desert. Less than 50 years after Zacharius Lewala found his diamond, Kolmanskop was a ghost town. But wooden homes in the desert don’t rot. Within a few years, sand had begun to drift into the open windows and doorways of the buildings as the Namib sought to reclaim its own. The entire complex is now a popular tourist destination, with half a century’s worth of dunes piled up inside the residences, ballrooms, theaters, and hospitals.

9Teufelsberg Listening Post

An artificial dome atop an artificial hill from a time of artificial fears, this abandoned Cold War–era radar post outside Berlin, Germany, rises from the forests like a phallic beacon shining its turgid light upon the pages of a confused history. Built in 1963, the listening post was used by the US National Security Agency to allegedly intercept military and diplomatic communications during the Cold War. Records are vague as to the exact nature of the work performed there, and with the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1991, the place was gutted, and the station was abandoned to the elements. Perhaps even more interesting than the station itself is the history of the Teufelsberg hill on which it stands. The hill—the highest point in Berlin—is actually a massive heap of the city’s rubble from World War II, all dumped over a Nazi military college that’s still intact somewhere beneath all those tons of debris. Since the listening station powered down in 1991, the facility has changed hands frequently. Each new buyer begins with an ambitious goal to convert the bulbous radomes into a hotel or resort or museum or what have you, but so far, every plan has fallen through, leaving the odd structures to serve merely as gravestones for the corpse of a past Berlin. The facility is currently off-limits, but trespassers say the view of the city from the top is incredible.

8Boston’s Long Island

Boston’s Long Island doesn’t want to be inhabited. Not to be confused with the similarly named island in New York, this 2.8-kilometer (1.75 mi) stretch of land in the Boston Harbor has been the site of numerous failed projects since its original colonization in the 17th century. Its rocky shores and overgrown hills host a derelict military fort, vacant hospitals, mysterious graves, and a laundry list of alleged government secrets. The region’s violent history began in 1675, when English settlers shipped hundreds of Native Americans to the islands in the harbor and left them to fend for themselves on the barren rocks over the harsh winter of 1675–1676. Most of them died of starvation. In World War II, Nazi scientists were smuggled onto Long Island by the federal government as part of Operation Paperclip. In fact, the island is believed to be the inspiration for the novel Shutter Island by Dennis Lehane. Most recently, the island housed a shelter for Boston’s homeless, but that was hurriedly closed down in 2014, leaving rows of empty bunks inside the old tuberculosis ward. Citing safety concerns as the reason for the island’s evacuation, Boston’s Mayor Martin J. Walsh closed down the Long Island Bridge and transported every inhabitant to the mainland, turning the island once again into a ghost town.

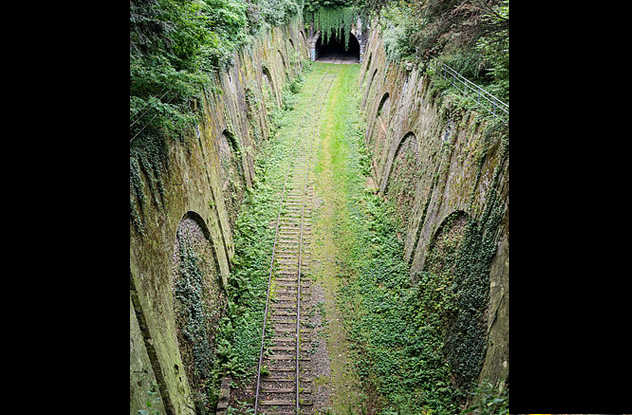

7Paris’s Hidden Railroad

In 1841, Paris was just wrapping its head around the idea of rail transport. It had recently finished a massive fortification project that ran around the perimeter of the city, and the military was looking for ways to get troops and supplies from the center of the city out to the strongholds. Strapped for cash, they turned to private companies to foot the bill for the railways, which soon radiated from Paris’s center to the outskirts in a star-shaped pattern. The result was a mess. Each line was operated by a different company, and nary did any two lines connect. Passengers from the perimeter had to travel into the heart of Paris just to catch a different train at a different station that would take them back out to a different point in the perimeter—sometimes just a short distance from their original departure point. So Paris decided to create the Petite Ceinture, or “little belt.” This line would form a circle just inside the city’s fortified perimeter and connect the other railways. It was a smashing success, and for nearly 100 years, it served as one of the main transport methods in Paris. Then, in the early 20th century, its rails and stations began to see less and less traffic, until it was practically abandoned by 1934. In the intervening years, the line has remained nearly untouched. It’s now grown over with moss and ivy, and few Parisians even know it exists. Via tunnels, bridges, and man-made gorges, the Petite Ceinture winds and twists through nearly 32 kilometers (20 mi) of modern-day Paris, a hidden natural belt in the midst of urban sprawl.

6Holland Island

Nearly 400 people once called Holland Island home. Mostly fishermen and their families, the island’s occupants carved a living straight from waters of the Chesapeake Bay for centuries. But eventually, the sea stopped giving and started taking. What was once an 8-kilometer-long (5 mi) island began to recede as erosion ate into the shoreline. Like many of the islands in the Chesapeake Bay, Holland Island is made mostly of silt and clay rather than rock, making it easy prey for the ceaseless force of wind and waves. The last inhabitants fled in 1922, leaving their homes and churches as bleak monuments to the people who once walked the island. Even those slowly fell into the sea. All but one, that is. The last house on Holland Island outlived its brethren by years, tenaciously holding its own on a wispy strip of land that goes completely underwater every high tide. It had help—for 15 years, a retired minister dedicated his life to preserving the two-story Victorian by surrounding it with timber, stones, and sandbags in a futile attempt to hold back the sea. Despite his best efforts, though, this strange landmark finally gave up the ghost and collapsed in 2010.

5Russia’s Tesla Towers

Reliable sources of information about these bizarre structures are few and far between. Located in the middle of a Russian forest, they’ve been dubbed “Russian Tesla towers” by most websites on which they’re featured. The towers are actually Marx generators, built to convert a low-voltage direct current into a high-voltage pulse. Systems similar to these Russian behemoths—although on a much smaller scale—are commonly used today to simulate lightning on industrial equipment. The Russian generator complex was built by the Soviet Union in the ’70s to test insulation for aircraft. When the Iron Curtain lifted in the early ’90s, the rest of the world got their first glimpse of the hidden testing facility, and it’s been in and out of the public eye ever since. Technically, it’s not abandoned, since periodically over the years it’s been put back into temporary use by private research companies.

4California’s Glass Beach

Near Fort Bragg, California, is a secluded beach awash in the bright colors of emeralds, rubies, turquoise, and diamonds. But these aren’t gemstones littering the sand—they’re bits of polished glass from 100 years of dumping in the area. Starting around 1906, the community of Fort Bragg—along with other cities along the coast—took to dumping their garbage straight into the Pacific. While the paper was churned to mush, and the plastic presumably floated to climes distant and unknown, the glass remained. It wasn’t until 1967 that Fort Bragg put the pinch on ocean dumping, but the seeds of transformation were already sown. Worked for a century by rolling waves and abrasive sand, the razor shards of glass eventually took on rounded edges and washed back up to shore as iridescent glass pebbles. Although glass isn’t a rarity, there are bona fide historic relics strewn along the beach: After World War II, auto companies switched from glass to plastic for the manufacture of taillights, which makes the odd ruby-colored glass pebble something of a collector’s item. However, Glass Beach is now a part of MacKerricher State Park, so it’s illegal to pocket any of the sea glass.

3Angola’s Ghost City

On an isolated swath of countryside a few miles outside of the capital city of Angola is a modern high-rise ghost town. Nova Cidade de Kilamba—usually shortened to just “Kilamba”—contains 2,800 apartments split between 750 high-rise buildings. It was built to house close to half a million people and comes complete with its own schools and retail section. And it’s almost completely empty. The miniature city was financed by a Chinese construction company and went from scrub land to completed project in less than three years. But rather than the influx of residents they probably expected, the only life to be seen in the entire 12,000-acre complex are a few Chinese workers (who live off-site) and a scattering of disoriented animals. According to the BBC, the problem is that Angola’s class structure consists of “the very poor and the very rich,” so there’s nobody in the market for a $200,000 apartment.

2The Maunsell Forts

Like metal beasts risen from the murky depths, the Maunsell Forts stand guard at the mouth of the Thames to this day. Although they aren’t quite as useful as they used to be, they serve as silent reminders of our turbulent past. As the threat of German air raids over Britain in World War II abruptly became reality, the Ministry of Defence commissioned several sea forts to protect the country’s airspace. In addition to four naval forts, the army also built six forts for anti-aircraft defense. Three of these were dropped in the Mersey River, and three were put in the mouth of the Thames estuary. Of the three Thames forts, only two are still around—Red Sands Fort (pictured above) and Shivering Sands Fort. The forts were decommissioned after the war and abandoned after their guns were removed. Most of them are now derelicts, leftover curiosities from a time of war, although one of the naval forts was later invaded by a lone Englishman, who declared it the newly minted Principality of Sealand.

1The SS Ayrfield

If you swim out past the mangroves of Homebush Bay in Sydney, Australia, and look to the northwest, you’ll see something incredible: the rusted hull of a 100-year-old steamer bursting with its own isolated forest sprouting from its decks like a post-apocalyptic chia pet. The SS Ayrfield was built in 1911 and put to use as a collier, transporting coal from the mainland to coal-fired ships stationed out at sea. During World War II, the Commonwealth requisitioned the Ayrfield as a cargo ship to get supplies out to Allied troops in the Pacific theater. After the war, it returned to its domestic duties under the care of the Miller Steamship Company until it was retired in 1972 and sent to its grave in Homebush Bay. For years, Homebush Bay has been the place where ships go to die. In fact, it’s where everything goes to die. From DDT to heavy metals to dioxin, the body of water has served as a chemical dumping ground for decades, choking out the native mangroves and turning a once thriving fishing ground into an industrial mistake. It’s since been cleaned up to a degree, and now only a few rusted ships are visible above the waterline. The SS Ayrfield is one of the remaining relics of the bay’s turgid past, a poetic reminder that not everything that dies has to stay dead. Eli Nixon is the author of Son of Tesla, a sci-fi novel about love, friendship, and Nikola Tesla’s army of cyberclones. He also has a Twitter.