Islands all but completely cut off from the rest of the world produce flora that is unique and looks as though they could grow only on an alien world. Other islands are mysterious because of their inhabitants’ origin or fate. All of these ten strange and mysterious islands are truly amazing for these reasons and more.

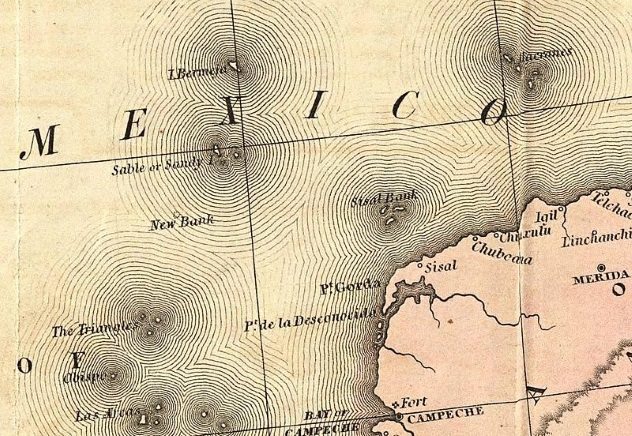

10 Isla Bermeja, The Lost Island

On maps dating as far back as the 1700s, Isla Bermeja was shown off the Yucatan Peninsula’s coast, at a greater distance than any other island claimed by Mexico. The island was just what the country needed to extend its claim on offshore oil and stop the United States’ encroachment on Mexico’s interests in that department. There was just one problem: A 2009 National Autonomous University of Mexico study concluded the island doesn’t exist—at least not where it’s supposed to be. Using underwater sensing devices and aerial reconnaissance assets, the search team couldn’t find the island anywhere in the area in which maps indicated it should be. The island is supposed to lie 55 nautical miles farther than Mexico’s 200-nautical-mile territorial limit. By claiming it, Mexico would extend its oil claims into the middle of the Gulf. Although the lost island wasn’t found, Elias Cardenas, the head of Mexico’s congressional Maritime Committee, planned to continue his country’s search for it, hoping it might turn up elsewhere. Perhaps the island had sunk or submerged, he said. Mexican conspiracy theorists had their own ideas about what happened to Isla Bermeja. Maybe the US bombed it, or it could have been a victim of global warming or an earthquake. Cardenas is certain that the bombing didn’t account for the mysterious island’s disappearance. “That would have been [ . . . ] very noticeable,” he said. The elusive island was first reported missing in 1997, when a Navy fishing expedition was unable to find it. Until it disappeared, Isla Bermeja, which supposedly measured 80 square kilometers (31 mi2), had been the point from which Mexico’s 200 nautical-mile limit started. Currently, the Alacranes islands have determined the end of the country’s territorial limits. As a result, Mexico’s “economic zone” has been “sharply reduced.”[1]

9 Vozrozhdeniya Island

During the 1920s, the Soviet Union officials were seeking a location with specific attributes. It had to be isolated, it had to be surrounded by desert, and it had to be within the borders of the Soviet empire. Two islands fit the bill. The Soviets chose Vozrozhdeniya, situated in the Aral Sea. There, a top-secret biological weapons laboratory was constructed, where the plague, anthrax, smallpox, brucellosis, tularemia, botulinum, and Venezuelan equine encephalitis pathogens were genetically modified to resist medical treatment. Gennadi Lepyoshkin, physician, microbiologist, and Soviet Army colonel, spent 18 years of his career on the island. In a year, he said as many as 300 monkeys would be caged on a range, next to instruments that measured the concentrations of pathogens in the air. Following the monkeys’ exposure to the germs, they’d be taken to labs, where their blood was tested, and the progression of the diseases in their bodies would be monitored. “They would die within weeks, and we would perform autopsies,” Lepyoshkin said. The 1,500 people involved in the project not only worked on the island but lived there as well in the only town, Kantubek, which provided “a social club, a stadium, a couple of schools and shops,” Lepyoshkin said. It was a “beautiful” place, where workers could swim in the Aral Sea or sunbathe on its shore. As the Aral Sea dried up, the island simply became part of the surrounding desert, and today, Kantubek lies in ruins, having been looted after the Soviet Union abandoned it. Scientists don’t believe the biological weapons laboratory poses much of a threat anymore. All the pathogens except anthrax, which can survive for centuries, have been destroyed by the area’s high temperatures and harsh conditions. When they left, the Soviets buried the laboratory’s anthrax spores to conceal the project’s violation of the 1972 treaty banning biological weapons. In the 21st century, US and Uzbek officials visited the site, burning warehouses that contained “remains of the previous experiments.” US Defense Department officials believe the anthrax spores have been destroyed, although no one can know for certain that such is the case.[2]

8 Bannerman Island

Bannerman Island, in the Hudson River, is a half-hour boat ride from New York City. There’s no other way to get there. Visitors to the mysterious island are likely to wonder why there’s a castle on it. The edifice was built by Frank Bannerman VI, who made a fortune by reselling surplus military equipment he bought at government auctions at the end of the US Civil War. He needed a place to store the huge quantities of black powder he’d purchased, along with other surplus items, when his son, David, mentioned Pollopel Island. Bannerman bought it in 1900, built a large arsenal there the next spring, and constructed a small castle atop the island, next to the arsenal, as his home, renaming the island after himself. When Bannerman died in 1918, construction ceased. The ferryboat was destroyed in a storm in 1950, and the island was abandoned. On August 8, 1969, a fire gutted the arsenal, and New York state, which had bought Bannerman Island and its buildings in 1967, declared the island off-limits. It reopened in 2017, and tour guides now recount the island’s mysterious history to curious visitors.[3]

7 Earthquake Island

The powerful earthquake that killed 39 people and toppled homes in Pakistan in September 2013 also created an island.[4] According to Pakistan’s chief meteorologist, Mohammed Riaz, it was magnitude 7.7, while the US Geological Survey in Colorado claimed it was magnitude 7.8. The island didn’t exist before the earthquake, but after the event, the Pakistan Meteorological Department’s director-general, Arif Mahmood, said locals reported witnessing the creation of the tiny island, measuring 100 meters (330 ft) in length and 9 meters (30 ft) high, near the port of Gwadar. Pakistani officials said the earthquake might have buckled land under the sea, creating the island, but further investigation would be conducted to determine the cause.

6 Poveglia Island

Back when the bubonic plague nearly half of the world’s population, the Romans had a clever idea to keep the healthy people separated from the sick. The plagued people were shipped off to Poveglia Island, a small, secluded landmass that floats between Venice and Lido. There, people lived out the last of their wretched lives together until they died. Since the island already reeked of death, the next time an epidemic came along, barely alive bodies were dumped there and burned in mass graves. In the 1920s, a mental hospital was built to welcome the island’s newest “guests,” or anybody that showed symptoms of any sort of sickness, physical or mental. Basically, if you had an itch, away you went to Poveglia where you’d sink your feet into the soil (half dirt, half-human ash) and be in the company of over 100K dead. At one point, an unscrupulous doctor ran the mental hospital, and since mental health was pretty unregulated back then, he conducted all kinds of brutal experiments on residents of the island (like shoving chisels into their brains to see what moved). The doctor committed suicide by jumping from the bell tower—one more soul added to the island’s strange and gruesome past. [5]

5 Floating Eye Island

Located in the Parana Delta, between the cities of Campana and Zarate in Buenos Aires Province in Argentina, is an island shaped like a nearly perfect circle with a diameter of 120 meters (390 ft). It is surrounded by a channel that also forms a nearly perfect circle. Thanks to the presence of the round landmass inside it, the channel looks much like a crescent moon. Together, the island and channel resemble an eye, an appearance that suggested the island’s nickname. “The Eye” floats; it also rotates on its own axis, film director Sergio Neuspiller said. The filmmaker discovered the Eye in 2016 while he was scouting locations for a science fiction movie. Having made the astonishing discovery of the mysterious island, Neuspiller and his crew, including Richard Petroni, a hydraulic and civil engineer from New York who’s become involved in the project, decided to make a crowd-funded documentary about the Eye, instead of filming the science fiction movie Neuspiller had originally intended to make.[6]

4 Socotra Island

Socotra Island, off the coast of Yemen, looks for all the world like an alien planet. Its endangered flora is unique due to the remote location’s isolation, temperature extremes, and arid conditions. A third of its plant life can be found nowhere else on Earth. Fortunately, 70 percent of the island has been set aside as a national park. Some of the plants look like turnips planted upside down. The branches of another, the crimson sap of which has earned it the name Dragon’s Blood Tree, are devoid of leaves, except at their tips, making it look as though the branches are the tree’s roots and the tree is growing upside down. The strange tree is used for its supposed medicinal value, to produce fabric dye, to make incense, and to stain wood. The island’s bottle tree, adapted to store water in a dry climate, has a thick trunk, and its few limbs, thick near the trunk, give rise to clusters of much thinner branches ending in thick clumps of green leaves. Surrounded by turquoise water, the island features huge limestone caves, homes to bats, the only mammal native to Socotra. Messages in a variety of languages have been carved into the caves’ walls. Researchers attribute them to sailors who stayed on the island between AD 1 and 6. The residents of the mysterious island are also unique: They all have a DNA haplogroup possessed by no other people on Earth, and some contend that the Garden of Eden was originally located on Socotra. In 2008, the UNESCO named Socotra a World Heritage Site.[7]

3 Diego Garcia

The vaguely U-shaped, 44-square-kilometer (17 mi2) atoll in the Indian Ocean known as Diego Garcia has thick, tropical jungles and white sand beaches. It was home to 2,000 native Chagossians until the British government forcibly relocated them between 1968 and 1973 so that the US could build a naval base there in exchange for Britain’s agreement to lease the island, which is of strategic importance because it’s located between East Africa, the Middle East, and Southeast Asia, allowing the US to strike locations in both Asia and the Middle East. Diego Garcia was used to stage air support operations during the 1991 Gulf War, the 2001 Afghanistan war, and the 2003 Iraq war. The remote, restricted island, some contend, is also the site of a secret US prison camp, although American authorities deny the truth of such speculations.[8]

2 Partridge Island

Canada’s Partridge Island, located off the coast of Saint John Harbour, New Brunswick, became a quarantine station in 1830. Immigrants stayed there, upon their arrival in Canada, to ensure that they didn’t spread shipboard diseases to Canadian citizens. Thousands of immigrants came to Canada during 1847’s Great Famine, and 2,500 Irish immigrants were quarantined on Partridge Island. The diseases against which the quarantine guarded from spreading included cholera, typhus, smallpox, scarlet fever, yellow fever, and measles. Newly arrived immigrants were subjected to kerosene showers followed by showers in hot water. Many were sick, and Partridge Island couldn’t handle the huge numbers who came to Canada during the peak of the Irish Potato Famine. The influx of thousands of Irish earned the island the nickname “Canada’s Emerald Isle.” Quarantined immigrants who died of disease were buried on the island, on one occasion in a mass grave, the grass over which was rumored to be of a more intense green than the surrounding lawn because the bones of the dead had nourished it. Closed in 1941, Partridge Island became a mysterious place “visited” only through photographs.[9]

1 Easter Island

Hoping Easter Island would give up its answer to their question as to how islanders had once lived there, farming thousands of miles from any continent, a team of researchers from the University of California at Santa Cruz used paleogenomic research to determine the genetic history of the Rapa Nui, as Easter Island’s lost people are known. It was believed the Rapa Nui interbred with South Americans well before Europeans arrived on Easter Island in 1772, but to the surprise of the UC Santa Cruz team, the materials from museums they tested indicated no contact between the Rapa Nui and South Americans before the arrival of Europeans, which earlier studies had, making the team’s finding somewhat controversial. If the results of their research prove correct, it’s clear that the Rapa Nui didn’t have help from South Americans in creating and moving the island’s heavy moai. Unaided, the Rapa Nui carved and moved them themselves. Raiders who kidnapped Rapa Nui to sell as slaves reduced their population from thousands to barely more than 100, and infighting and disease wiped out the rest, leaving their origin and, until recently, the creation of their statues, secrets as mysterious as the island itself.[10]