These Halloween traditions are not universal, though. Many countries have their own unique ways of celebrating this spine-tingling time of the year. From turnip jack-o’-lanterns to alcohol-filled pumpkins, the world has some truly surprising Halloween traditions to offer. Here are just a few of the best.

10 From Cabbage-Hurling To Devil’s Night

Around 2,000 years ago, the Celts of Britain and France celebrated the New Year on November 1, marking the end of the harvest. They believed the spirits of the dead would return to Earth and mingle with the living. The natives celebrated this spooky event with a festival of the dead, called Samhain. Locals engaged in a number of bizarre rites. One of the lesser-known traditions involved the humble cabbage. On October 30, little girls would unearth the vegetable and use it to work out what their future husbands would be like.[2] The cabbages were then used as projectiles to prank their neighbors. This peculiar event, called Cabbage Night, was first witnessed in Scotland and Ireland. The Irish and Scots eventually immigrated to the United States, bringing the tradition to parts of the Northeast. These vegetable-related high jinks eventually spread under different names, including Mischief Night, Devil’s Night, Mat Night (stealing doormats), and Gate Night (letting livestock escape). Today, most Halloween pranks are relatively benign (albeit annoying for the victims). Toilet-papered trees, flaming bags of dog feces, and egg-covered houses are the order of the day. But Mischief Night and Devil’s Night have also been associated with more serious criminal acts. During the mid-1980s, Detroit gangs were responsible for setting hundreds of vehicles alight on Devil’s Night. In 1991, Mischief Night brought out the worst in the people of Camden, New Jersey. The Camden Fire Department tackled a deluge of arson attacks across the city. It was the busiest day in the department’s history, with a record-smashing 133 fire calls. Smoke reportedly billowed from the city for hours.

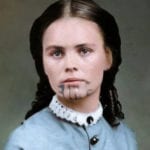

9 Turnips And The Legend Of Stingy Jack

The jack-o’-lantern is one of the most iconic Halloween decorations of all time. But why, to this day, do we walk around with hollowed-out fruits on October 31? To answer this, we turn to the Legend of Stingy Jack. The Legend of Stingy Jack (aka Jack of the Lantern) is an Irish tale about a swindler who was very frugal with his money. Stingy Jack was famous for his chronic drinking and manipulative behavior. The Devil, wanting to know what all the fuss was about, went to collect Jack’s soul. Upon realizing the Devil’s nefarious plan, Jack requested one last drink. Satan obliged and took his new friend to a nearby pub. Of course, neither party could pay for their refreshments. So Stingy Jack convinced the Devil to transform into a coin. That way, they could pay the barkeep. The Devil obliged, and Jack placed the coin next to a cross. The Devil was trapped, and Hell was without its prince. The Devil agreed to leave Jack alone for ten years in exchange for his freedom. Flash forward ten years, and Satan is ready to take Jack’s blackened soul. The trickster, now frail and elderly, asks the Devil to fetch an apple from a nearby tree. The Devil was not the brightest crayon in the pack, so he scrambled up the tree. Jack then carved a cross in the bark, stranding our blundering Beelzebub. Satan was left utterly humiliated and vowed to leave Jack’s soul alone. When Jack eventually died, however, he was turned away from the gates of both Heaven and Hell. The Devil, cackling with delight, gave his old nemesis a single burning ember. Jack made a lantern from a turnip and placed the ember inside. It is said that Stingy Jack’s lost soul is destined to roam netherworld for all eternity, his turnip lantern the only thing lighting the way. The Irish first started using hollowed-out turnips to keep the ghost of Jack at bay. But when Irish immigrants traveled to the United States, they discovered it was easier to carve the lanterns from pumpkins.[3] Turnip carving still exists to this day, particularly in parts of Scotland. In 2015, Britain was struck with a bout of wet weather that significantly affected the number of available pumpkins. As a result, the English Heritage charity started using turnips to decorate many of its own sites and recommended that others follow suit.

8 Soul Cakes

In the Middle Ages, the British baked soul cakes to honor the dead. These edible treats were typically made using cinnamon, ginger, nutmeg, and saffron. The cake’s raisin toppings were arranged in the form of a cross. During Hallowtide, beggars and young children were encouraged to knock on their neighbors’ doors and pray for the souls of their departed relatives. Inspired by the pagan folk plays of Samhain, the children would chant special souling songs. In exchange, these “soulers” were rewarded with soul cakes and other treats. Although soul cakes are now unheard-of throughout much of the West, some countries still practice this rather quaint tradition. Souling continues to take place in small pockets of Britain, Portugal, and France. Thankfully, for those who enjoy a spot of baking, the Internet is peppered with an assortment of soul cake recipes.[4]

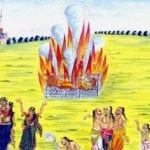

7 Hags, Heads, And Animal Sacrifice

Samhain represented the conclusion of the harvest season and the coming of winter. It was theorized that the wall between the living and the dead would weaken, allowing the spirits to return home. During this time, livestock were rounded up and slaughtered. The animal hides were then fashioned into costumes. Some superstitious locals used these animal skins to disguise themselves and ward off evil spirits. Others dressed up to celebrate the dead and welcome their return.[5] Samhain was a time when young men donned spooky costumes to dupe other households. These demonic doppelgangers were used to trick unsuspecting people into surrendering their food and drink. In Wales, some Celtic men dressed up as women and were known as the hags. Historians believe this is what spawned today’s trick-or-treating and Halloween garments. The Celts lit enormous bonfires and made sacrificial offerings to the gods. Animal skins and heads were worn during these otherworldly ceremonies. In recent times, there has been some concern over animal sacrifice. It remains unclear whether there is any significant uptick in animal sacrifices over Halloween. However, a number of animal shelters prevent the adoption of black cats around this time, just in case occultists try to use them for blood sacrifices. According to occult researcher Marcos Quinones, animal sacrifices take place in every US state, virtually all year round.

6 The Day Of The Skull

The Day of the Skull is a tradition celebrated in Bolivia. Across the nation’s capital of La Paz, residents collect and decorate the skulls of the dead. The skulls are often handed down from one generation to the next and prettied up with hats, glasses, flowers, and coca leaves.[6] Many residents take the skulls, or natitas, from abandoned graves. Outside of Bolivia, most would consider such behavior a tad eccentric, including the Roman Catholic Church. The Church has had limited success in trying to discourage Bolivians from keeping the skulls. Despite widespread aversion to the Day of the Skull, the practice is not proscribed. A week after All Saints’ Day, locals flood into the General Cemetery in La Paz. There, the worshipers sit through a service with their prized craniums. Mariachi bands play lively music, and residents sing and dance in local cemeteries. The skulls are given offerings of food, cigarettes, and prayers throughout the day. But why skulls? It turns out that many of Bolivia’s poor still retain superstitious beliefs. They believe there are a total of seven souls, one of which is contained within the skull. Natitas serve as amulets, guaranteeing their owners protection and good fortune. The ancient tradition has been credited with a great deal, from solving crimes to aiding youngsters with their university studies.

5 The Double Ninth Festival

Legend tells of a man, named Huan Jing, who saved his fellow villagers from pestilence. It was thought that a disease-bearing “river monster” was picking off the villagers, one by one. Huan Jing sought counsel from Fei Changfang, an immortal trained in the arts of magic. On the eighth day of the ninth month of the lunar calendar, the villagers tried to escape through a mountain passage. But Changfang had another idea. He told his apprentice to return to the village and mix chrysanthemum wine with dogwood leaves. The intoxicating scent confused the river monster long enough for Huan Jing to launch a surprise attack. On the ninth day, Huan used Changfang’s sword to slay the evil monster. With that, the plague was brought to a dramatic end. The Double Ninth Festival is celebrated in accordance with this tale. It is celebrated in many parts of Asia, including China, Japan, and Vietnam. Festivities involve drinking chrysanthemum tea, baking Double Ninth cakes, sporting dogwood fashion accessories, and climbing mountains. In 2017, around 10,000 seniors trekked up a mountain in Northeastern China’s Zhoushan city. The festival is typically used as chance to remember the dead. Many families hold ceremonies, visit the graves of their loved ones, clean headstones, and leave offerings. Others celebrate by honoring the elderly. In 1989, the Chinese government officially recognized the Double Ninth Festival as Seniors’ Day.[7] Schoolteachers now take their pupils on trips to retirement homes to interact with the elderly. This year’s Double Ninth Festival took place on October 17.

4 Night Of The Pumpkins

Halloween is celebrated over the following three days in Spain: Day of the Witches (October 31), All Saints’ Day (November 1), and Day of the Dead (November 2). Many parts of Spain share similar Celtic traditions to other Western nations. On Halloween, residents carve pumpkins and go trick-or-treating. However, the Galicia community, in the northwest of Spain, use pumpkins a little differently. They call October 31 the Night of the Pumpkins (Noite dos Calacus).[8] Watch this video on YouTube The Galicians fill hollowed-out pumpkins with a drink called queimada. The alcoholic punch is made using coffee beans, orange peel, cinnamon, and liquor. The resultant mixture is then set alight. The brewer ladles the flammable drink into the air, producing streams of fire. A spell is recited as the concoction is brewed. Framed copies of this incantation are sometimes displayed in local taverns. Queimada is supposed to cast out demons and ghosts while purifying those who drink it. The ritual, in its entirety, can be seen above.

3 Allhelgonadagen

The Swedish version of All Saints’ Day (Allhelgonadagen) was originally celebrated on November 1. In 1953, the event was moved to the Saturday between October 31 and November 6. Swedish All Saints’ Day is celebrated in the same vein as many Latin American countries. Locals visit the graves of their dead, leaving flowers, wreaths, lanterns, and candles.[9] Nighttime during Allhelgonadagen is a spectacular sight to behold. Entire cemeteries are aglow as people pay their respects. American-style Halloween traditions only started appearing in Sweden in 1982. The owner of a party store called Butterick’s imported his Halloween decorations from the United States. In an interview with the media, Managing Director Bengt Olander confessed that he only sold the decorations to appease his American wife, who had “nagged [him] for some years.” And it was a good thing Olander listened. His Halloween products sold quickly, putting his Stockholm department store on the map. Olander was forced to get into the Halloween spirit, once again, when his ten-year-old daughter asked for a jack-o’-lantern. Since pumpkins are a limited commodity in Sweden, the dutiful father created a plot for his daughter to start growing her own gourds.

2 Bread Of The Dead

One of the most important public holidays in Mexico is Dia de los Muertos, or the Day of the Dead. The event spans from October 31 to November 2. It is an occasion to honor the dead and visit the graves of lost relatives. Children are encouraged to build altars (ofrendas) to attract the spirits.[10] It is thought that child spirits will return on the Day of the Innocents (Nov. 1) and that adult spirits will return on the Day of the Dead (Nov. 2). These altars are placed near headstones, boasting marigold flowers, food, photos, and family trinkets. Family members maintain the grounds and often use incense to purify the gravestones. Special foods are cooked to celebrate the occasion, including “bread of the dead” (pan de muerto) and sugar skulls. The bread of the dead is a sweet, circular bun that traditionally features patterns of skulls and finger bones. A single teardrop shape is often molded into the bun, representing the grief of losing a loved one. A similar culinary tradition is observed in Southern Europe. Italians celebrate the Day of the Dead with “beans of the dead” (fave dei morti ). The “beans” are actually almond-flavored cookies that look vaguely reminiscent of fava beans. The shape is quite deliberate, however. In ancient Rome, it was thought that the souls of the dead were held within beans. Meanwhile, Pythagoreans believed that the bean plant’s hollow stem served as a ladder between the realms of Hades and Earth.

1 Kite Flying (But Spookier)

You might think it difficult to draw a connection between kites and the dead, but the Guatemalans have done just that. Every year, on November 1, the townsfolk of Sumpango and Santiago hold their renowned kite festival. Kite makers spend months laboring on their colorful designs. Many of the bamboo-strapped structures are enormous, reaching spans of up to 12 meters (40 ft).[11] Guatemalans first created the behemoth kites to protect against evil spirits. Superstitious inkling told them that the rustling of tissue paper scared the spirits away. Now, the kites are predominantly used to commemorate the dead. The event is officially named the Festival of the Giant Kite (Feria del Barrilete Gigante). The kites are flown over the local cemeteries, where locals pay their respects and leave offerings. However, the festival serves a dual purpose. In addition to honoring the dead, many Sumpango kite makers aim to deliver political messages. The kites are often labeled with slogans which criticize government policy and call for peace. More personal messages are tied to kite tails and flown up to the awaiting spirits.