At the Democratic National Convention of 1948, delegates officially adopted a pro-civil rights platform for the first time, which was quickly embraced by President Harry Truman. Some Democrats, however, did not like this at all, and the delegations from a number of Southern states marched out of the convention to have their own. This breakaway party called themselves the “States’ Rights Democrats” or the “Dixiecrats,” and they nominated then-Governor Strom Thurmond of South Carolina for the presidency. Running under the slogan, “Segregation Forever,” Thurmond hoped to keep the federal government from ever interfering with the Jim Crow laws that his party valued so much. Even though their message did not play well throughout most of the United States, the Dixiecrats managed to win the electoral votes of Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama and South Carolina. Thurmond’s third-place finish might seem impressive by today’s standards, but in reality his loss allowed Democrats to reject segregationists and to support the Civil Rights Movement – which two decades later finally succeeded.

Strom Thurmond wasn’t the only Democrat who felt betrayed by the party platform in 1948. Henry Wallace was the former Vice-President who had served under Franklin Roosevelt, but was replaced by Harry Truman in the Election of 1944. Wallace’s main beef with the party, however, had nothing to do with segregation (which he opposed), and everything to do with the Soviet Union (which he supported). In his first term as president, Harry Truman called for an aggressive stance against Communism and, in particular, the Soviet Union under Josef Stalin. Former Vice-President Wallace, however, did not like this part of the Democratic platform. So in response, he decided to run for the presidency as the Progressive Party candidate – which had a platform emphasizing trust in Stalin and giving American Communists a voice in government. In fact, Wallace’s Soviet-friendly stances were extreme enough that even many socialists refused to support him. On election day, the Progressive Party failed to win a single state or electoral vote, which further pushed American Communists into obscurity. Wallace retired from politics after his loss, and in time grew to regret his opposition to the policies of Harry Truman and the Democratic Party.

In 1872, Horace Greeley was a newspaper publisher and former one-term congressman from New York. He had also been an ardent abolitionist and a founding-father of the Republican Party. But after the Civil War, he grew to despise the presidency of Republican Ulysses S. Grant – who favored the continuation of Southern Reconstruction. Greeley thought that the South had been punished hard enough, and called for a withdrawal of Union forces from the former Confederacy. When Grant was up for re-election in 1872, Greeley ran for, and subsequently won, the nomination of the “Liberal Republican Party”. Surprisingly, the Democratic Party loved his platform of ending Reconstruction so much that they decided to nominate him too. The American people, however, were not quite as enthusiastic about Greeley, and on election day he suffered an embarrassing loss to Grant, only winning a handful of former slave states. But even if he had won, Greeley would have never made it to the presidency, since a month after the election he went crazy and died a few days later.

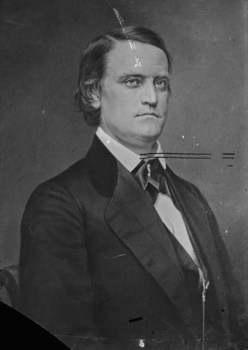

Despite having dominated politics throughout the 1850s, the Democratic Party of 1860 was in serious trouble. Over the issue of slavery, the Party was split in two. One faction, the “Northern Democrats” under Senator Stephen Douglas of Illinois, was more moderate and supported the rights of people in their own jurisdictions to decide whether slavery should be legal or not. The other group that emerged was the “Southern Democrats,” which supported government protection of slavery as a property right. They nominated incumbent Vice-President John C. Breckenridge, a politician from Kentucky, for the presidency. Running on his hard-line pro-slavery platform, he became the favorite candidate of the American South. But the splitting of the Democratic Party allowed for another candidate – former Congressman Abraham Lincoln of Illinois – to dominate in the North, which was at the time the most populous and held the most electoral votes. Lincoln thus managed to win the presidency against both Democrats, as well as third-party candidate John Bell. After Breckenridge lost the election, the Civil War began and he soon joined the Confederacy.

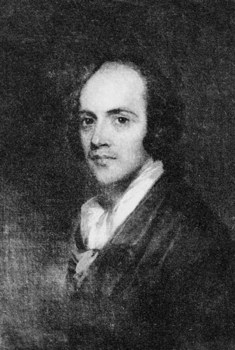

The Presidential election of 1800 may be one of the most bizarre in American history. Incumbent President John Adams, a Federalist, was running for re-election. His challenger happened to be his own vice-president, Thomas Jefferson, who represented the Democratic-Republican Party. Adams was unpopular and indeed handily lost the election to Jefferson. But in those days the Constitution still had a few kinks in it, and one of those kinks was the rule that each presidential elector must vote twice, for two different individuals, and the runner-up would become vice-president. So Jefferson’s 73 electors each cast one vote for him, and one vote for his vice-presidential candidate Aaron Burr. This resulted in an electoral tie between Jefferson and Burr, and as a result the Federalist-controlled House of Representatives had to choose between the two men. Jefferson was not popular with the federalists, and they attempted to elect Burr. For a while there was no consensus, with Jefferson a few votes short of being elected. But eventually, former Secretary of the Treasury, Federalist Alexander Hamilton gave his support to Jefferson, thus handing him the presidency, while the Vice-Presidency went to Burr. Mr. Burr apparently didn’t like this very much. A few years later he challenged Hamilton to a duel, which he won handily by killing him. But this is not the scariest aspect of Aaron Burr. After killing the popular Hamilton, he was widely despised throughout the United States. So what did Aaron Burr do? He devised a conspiracy against United States which involved aiding Britain in regaining some of it’s former territories lost in the Revolutionary War. Additionally, he hoped to acquire the land west of the Mississippi to form his own personal empire, which he would use to antagonize the United States. Unfortunately for him, and luckily for the existence of America, Burr was caught and charged with treason. Even though he was acquitted, Burr was hated more than ever and spent the majority of his remaining life in exile. Makes you kind of glad that this man didn’t become president, doesn’t it?

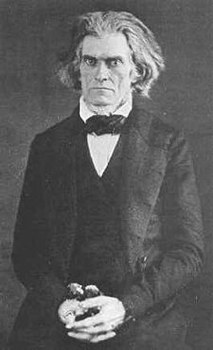

Calhoun is best remembered as a vice-president, but in the early stages of the 1824 election, he was a candidate for the presidency – thereby earning himself a bonus place on this list! Calhoun served as vice-president under two presidents and undermined both of them. Calhoun led the pro-slavery faction in the Senate in the 1830s and 1840s, opposing both abolitionism and attempts to limit the expansion of slavery into the western territories. He was also a major advocate of the Fugitive Slave Law, which enforced the co-operation of free states in returning escaping slaves. Furthermore, Calhoun felt that having a separate, distinct Indian culture within the borders of the United States would create problems in such areas as land usage, interracial relationships, and trade. His beliefs that Indians were inferior steered Calhoun to support a policy of the removal of the Indians in the eastern United States. Many of Calhoun’s policy ideas were implemented during his tenure as Secretary of War and Vice-President. He believed that government interference in the lives of Indians was essential because the Indians were too ignorant and uncivilized to be allowed to make their own decisions and live as they chose. During the Civil War, the Confederate government honored Calhoun on a one-cent postage stamp, which was printed but never officially released. This article is licensed under the GFDL because it contains quotations from Wikipedia in the bonus item.