10 The Cemetery Gun

The Museum of Mourning Art in Drexel Hill, Pennsylvania, holds a weapon that loved ones of the recently deceased would use to protect the dead from “resurrection men,” who dug up cadavers for profit. Invented in the 1700s, they simply called the machine “the cemetery gun.” It was a gun mounted at the foot of a grave that could rotate 360 degrees. The gun was rigged with thin trip wires to catch thieves entering at night, when the groundskeeper was off-duty. If a thief triggered it in the dark, the gun would swing in their direction and fire. After a while, the resurrection men figured out a plan to avoid getting shot. They would send women “mourners” to visit the graveyard in the daytime to see if the family had paid for a cemetery gun. This way, they knew which locations to avoid at night. These machines were rented by the week, and they were expensive. The idea was to protect the body long enough to make it useless to steal and sell as a medical school cadaver. In the end, only the rich could afford to rent a cemetery gun, which meant that the bodies of lower-class citizens were easier targets.[1]

9 Triple-Layered Coffin

In the United Kingdom in the 1800s, body snatchers were a very well-known problem. On top of that, in 1828, the infamous murderers William Burke and William Hare murdered 17 people to sell them to Dr. Robert Knox, who wanted to study the fresh cadavers of people who were healthy when they died. That same year, a man called Mr. Dowling lost his wife and baby during childbirth.[2] Obviously, he would have been shocked by the sudden loss of his young family, but he was also understandably terrified that his loved ones’ bodies would be stolen. In order to stop this, he kept the corpses around the house for several weeks until they began to decompose. Once the bodies were rotting away, he placed his wife and child inside a lead coffin. However, that wasn’t enough. The lead coffin was then placed inside a larger wooden coffin. Like Russian stacking dolls, this double-layer coffin was put in a third wooden casket before the whole thing was buried in the ground.

8 Curse

When William Shakespeare knew he didn’t have much time left on Earth, he feared that his remains would be either stolen by grave robbers or possibly moved to a new location. In order to prevent this from happening, he set a curse upon anyone who tried to move his body.[3] Shakespeare’s tomb is located in the Holy Trinity Church, Stratford-on-Avon, Warwickshire, England. Before he died, the man wrote one final poetic message for the world: Good frend for Jesus sake forebeare, To digg the dust encloased heare; Bleste be the man that spares thes stones, And curst be he that moves my bones. Curses were not a new topic in Shakespeare’s plays. One of the most famous lines in Romeo and Juliet is, “A plague on both your houses!” This curse is followed by a series of unfortunate events and deaths. Shakespeare’s posthumous threat worked, as no one ever tried to tamper with his grave. One would hope that it was out of respect for his work, but since his death in 1616, anyone with an inkling of superstitious beliefs would steer clear from his grave.

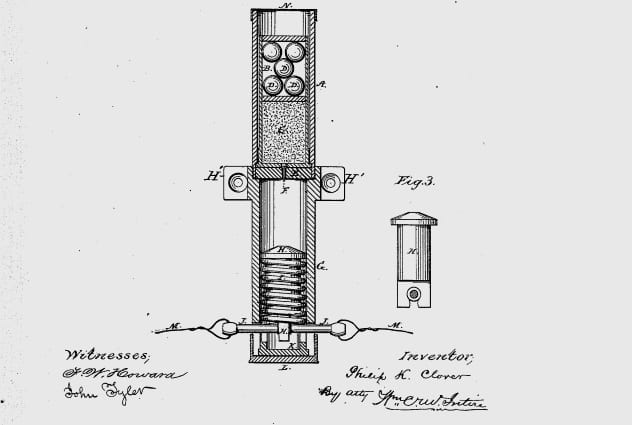

7 Coffin Torpedoes

In 1878, coffin torpedoes were patented by Philip K. Clover. In his patent, he describes the invention as “a means which shall successfully prevent the unauthorized resurrection of dead bodies.” His torpedo was attached to the coffin and would be discharged as soon as anyone tried to rob a grave. He goes on to explain that this invention is fully intended to kill or seriously injure any grave robber who tries to steal a dead body. According to The Stark County Democrat, in Canton, Ohio, in 1881, a group of three body snatchers were trying to steal a body in the middle of January. Normally, two men would dig up the body and put it on their sled, while the third acted as a lookout. However, when the two diggers pushed their pickaxes and shovels into the earth, the coffin torpedo exploded. It killed one man and blew other’s leg off. The third man ran over to his friends, put their bodies on the sled, and carried them away.[4]

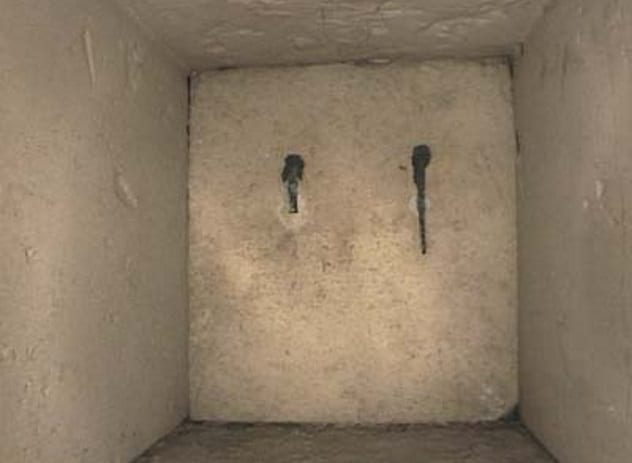

6 Sliding Portcullises And Secret Doors

The ancient Egyptians buried their pharaohs in complicated underground chambers in order to protect the treasure that was laid with the royal remains. Sliding portcullises were doors that the architects of pyramids would prepare on the edge of a ramp in a tight hallway shaft. Once the construction of the tomb was complete, they would take away a support to trigger a heavy slab of stone to slide down and cover the doorway.[5] Robbers could not move these heavy stone doors, especially since to do so would require pushing them up a ramp. Even if they managed to do that, the stone would still be blocking the entryway. Thieves tried to get around this by digging underground tunnels that would allow them to enter the grave. However, architects constantly changed the locations of the entrances to the tombs. In fact, one pyramid didn’t have any entrance at all. The body and treasures were lowered into the hole in the top of the pyramid, and the pointed tip was placed on top, permanently sealing the grave.

5 The Mortsafe

In early 19th-century Scotland, people began to fasten iron cage frames, called “mortsafes,” around graves. They were essentially coffin-shaped iron cages that would lay on top of the wooden coffin. The cage was so large that it surrounded the grave above the ground. Several men were needed to lift a mortsafe and place it on top of the coffin. It was so heavy that the only way to remove it was to gather a group of men and use a mechanism called a “mortsafe tackle” to help leverage the weight. It was impossible for a group of two to three resurrection men to remove a mortsafe when they snuck in at night.[6] Many graveyards began to keep one or two mortsafes on hand and rented them to families for one shilling per day. The idea was to keep the body inside the mortsafe until it became so decomposed that resurrection men could no longer steal it. Then, the coffin would be dug up, and the metal frame would be rented to another family. Some families that could afford to do so actually purchased their own mortsafes from local blacksmiths. That way, the bodies of their loved ones were permanently protected by a cage. Some of these mortsafes can still be found in Greyfriars Kirkyard in Edinburgh.

4 Liquid Mercury

Throughout the ancient Chinese emperor Qin’s massive tomb, thousands of likelike clay statues of soldiers stand guard. They even once held real weapons to protect their leader in the afterlife. When the statues were first made in 208 BC, they would have been painted to look even more realistic. Aside from the clay army, Qin Shi Huang Di’s grave was filled with toxic pools of liquid mercury. During his time, the Chinese practiced alchemy, and mercury was thought to be the key to immortality. However, the huge amount of this poisonous substance has made it nearly impossible for modern archaeologists to properly excavate the site. Many sections still haven’t been explored.[7] In Mexico, Teotihuacan’s Pyramid of the Plumed Serpent was built to house the body of their emperor when he died. In 2016, archaeologists discovered that there was a pool of liquid mercury underneath the grave site. Some historians speculate that this may have some religious significance. Whether or not these ancient peoples intended it for that purpose, liquid mercury has become a very effective way to ensure that their dead leaders can rest in peace without being disturbed.

3 The Army

In Palestine, there are multiple tombs that hold the bodies of sacred religious figures. These holy sites are frequented by Jewish and Christian tourists, which means that they’ve been a perfect target for anti-Jewish aggressors during the ongoing Israeli-Palestinian conflict. In 2000, the burial site of Joseph, son of Jacob, was damaged by bombs. The damage was repaired, but in 2015, Joseph’s tomb was attacked again by arson. The historic site was severely burned, and many parts needed to be rebuilt again. These attacks have led the Israeli army to step in and begin protecting the burial site. Jews are only allowed to visit once a month after nightfall while they are accompanied by the army. The assaults on Joseph’s tomb were even enough to warrant an emergency meeting of the United Nations.[8] Rachel, another prominent Biblical figure, also has a tomb in Bethlehem. In 2017, a group of Palestinian teenagers threw bombs at the site. Thankfully, no one was injured, and the tomb wasn’t damaged. It is likely that these religious landmarks will continue to be attacked, unless the land manages to find peace.

2 Underwater Tomb

In AD 681, the Korean king Munmu died. During his lifetime, he had united all of Korea and successfully protected the nation from Japanese invaders. He believed that the only way to continue protecting Korea from beyond the grave was to be buried underwater so that he could reincarnate into a sea dragon.[9] Today, tourists can still visit Munmu’s watery grave site. However, to the naked eye, it just looks like a small, rocky island. In the center of that island, there is a small pond. Some historians believe that Munmu’s ashes were scattered in the water surrounding the rocks and that the term “tomb” is merely symbolic. Others believe that the ashes are stored in an urn that was buried underneath stone slabs at the bottom of the pond. Despite the fact that the location of Munmu’s tomb has become public knowledge, no one has attempted to excavate it. This may be out of respect for the dead—or because there is no treasure buried with the king.

1 Satellite Images

In Egypt, tomb raiders still continue to loot ancient tombs for antiquities to this day. They aren’t gentle with these sites. They typically blow up the hidden entrances with dynamite, which destroys countless numbers of precious artifacts. Thieves gather whatever they can to sell on the black market. The amount of looting rose in 2008 during the global financial crisis and then dramatically increased again after the 2011 Egyptian revolution. Sarah Parcak, the winner of the $1 million TED Prize in 2016, has created a new program that will help to stop criminals from destroying these historical artifacts. Using satellite images, she is able to track where and when looting has occurred. During her research, she’s already helped to find previously undiscovered pyramids using the satellites. This has helped true archaeologists to reach the sites before the robbers so that they can excavate the items properly. Parcak plans to share this data with the local governments. Her hope is that these satellites can eventually work like security cameras that will notify local authorities when a robbery is taking place.[10] Shannon Quinn (shannquinn.com) is a writer and entrepreneur from the Philadelphia area.