For the sake of consistency, animals falsely thought to be extinct have not been included (coelacanth, Chacoan Peccary, ivory-billed woodpecker).

The Devil Bird, or Ulama, is a frightening horned bird of Sri Lankan folklore. This elusive creature is rarely seen, but is often heard in the form of its infamous, blood-curdling screams. Its cries are said to resemble a wailing woman and are perceived by locals as an omen of death. For centuries, the nocturnal cries of the Devil Bird were the only evidence of its existence; Western science wrote if off as mere superstition. Then, in 2001, the Devil Bird was identified as a new species of owl, the spot-bellied eagle owl (bubo nipalensis). The largest of all Sri Lankan owls, the bubo nipalensis matches the description of the Ulama perfectly, down to its characteristic screech and tufted “horns”. Although some debate still remains as to the true identity of the Devil-Bird, the spot-bellied eagle owl stands as the most compelling source of inspiration for this mysterious creature.

In Medieval folklore, the Ziphius, or “Water-Owl”, was a monstrous nautical creature said to attack ships in the northern seas. It possessed the body of a fish and the head of an owl, complete with massive eyes and a wedge-shaped beak. “Ziphius”, meaning “sword-like” in Latin, may refer to the beast’s fin, which was said to pierce the hulls of ships like a sword. Today, the inspiration for the Ziphius is known as Cuvier’s Beaked Whale, a widespread species of beaked whale. Also known as the Goose-beaked whale, this creature is found as far north as the Shetland Islands and as south as Tierra Del Fuego at the tip of South America. It is the only member of the genus Ziphius, which bears the name of its legendary identity. Some additionally attribute the inspiration of the Ziphius to the orca or the great white shark, based on some depictions of the beast as a predator to seals.

The Bondegezou (“man of the forests”) is a legendary, ancestral spirit of the Moni people in Western Indonesia. Described as a tree-dwelling creature, the Bondegezou resembles a small man covered in black and white fur. It is said to be a tree climber, but often stands on the ground in a bipedal stance. In the 1980s, a photograph of the Bondegezou was sent to Australian research scientist Tim Flannery, who initially identified the creature as a young tree kangaroo. But in May, 1994, Flannery conducted a wildlife survey of the area and discovered that the animal in the picture was new to science. The Dingiso (Dendrolagus mbaiso), as the creature is also known, is a forest-dwelling marsupial with bold coloration that spends most of its time on the ground. The Dingiso remains a rare sight – the first real evidence of the creature was only skins, and to this day, no Dingiso exists in captivity.

Early explorers to Australia described bizarre creatures never before seen by Europeans. They wrote of creatures with heads like deer that stood upright like men and hopped like frogs. The creatures sometimes sported two heads – one on their shoulders, and one on the stomach. Such accounts were understandably disregarded and ridiculed by fellow colleagues. That changed in the 1770s, when a dead specimen of this odd beast was exhibited in England as a public curiosity. Today, this creature is known as the kangaroo, a widespread marsupial endemic to Australia. Well-known for their leaping abilities and the female pouch for carrying young (marsupium), kangaroos are a nationally recognized icon of Australia. Four species of kangaroo exist: the Red Kangaroo (Macropus rufus), the Western Grey Kangaroo (Macropus giganteus), the Western Grey Kangaroo (Macropus fuliginosus), and the Antilopine Kangaroo (Macropus antilopinus).

When European naturalists first encountered this bizarre creature, they were understandably baffled. Accounts described it as a venomous, egg-laying mammal with a duck bill and beaver tail. Many prominent British scientists deemed it a hoax when presented with a sketch and pelt, in 1798. Even when offered a corpse, scholars suspected that it was an elaborate, sewn-together fraud. Today, this bizarre but fascinating creature is known as the platypus, one of only five extant monotremes (egg-laying mammals). While formerly recognized by science, it is no less unique today: this semi-aquatic creature, native to eastern Australia, swims with webbed feet, uses electrolocation to hunt, and possesses an ankle spur that, in males, can deliver a powerful injection of venom. While non-lethal to humans, this venom is excruciatingly painful and is not responsive to most pain-killers.

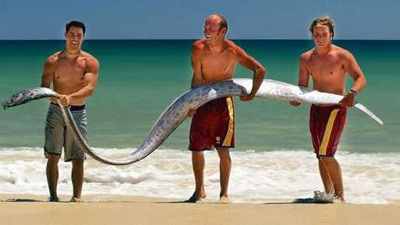

For centuries, the Sea Serpent persisted as the most captivating cryptozoological mystery in the world. Sightings of these mysterious, and often frightening, creatures have occurred plentifully throughout history, even up until the early twentieth century. From northern European waters to the Eastern North American coast, tales of serpentine, aquatic beasts of colossal proportions dot the globe. Their descriptions vary, ranging from horse-headed creatures to massive snakes. Cryptozoologists speculate that various misidentified animals can account for Sea Serpent sightings. However, one elusive species is a particularly likely source for many of these accounts. The oarfish (or ribbonfish) is a massive, elongated fish found worldwide. It is the longest of all bony fish, the largest recorded being 17 meters (56 ft) in length. Oarfish typically dwell in the deep ocean, but are occasionally washed ashore in storms, and linger at the surface near death. A live oarfish was filmed for the first time in 2001, demonstrating its rarity and reclusive nature.

By the early twentieth century, Western science had determined that giant lizards were nothing more than a relic of the prehistoric past. Thus, when pearl fishermen returned from the Lesser Sunda Islands, in Indonesia, with tales of monstrous “land crocodiles”, their accounts were met with overwhelming skepticism. An expedition from the Buitenzorg Zoological Museum, in Java, produced a report of the creatures, but the legendary dragons of Komodo faded into obscurity as World War I took precedence. Then, in 1926, an expedition from the American Museum of Natural History confirmed that the tales of giant lizards were true. W. Douglas Burden, the leader of the expedition, returned with twelve preserved specimens and two live ones. The world was introduced to the Komodo Dragon, a massive monitor lizard that grows up to ten feet, making it the largest lizard in the world. Komodo Dragons possess massive claws and fangs with which they can kill almost any creature on the island, including humans and water buffaloes. One particularly bizarre attribute of these creatures is their venomous bite, which has been attributed to bacteria-laden saliva or venom glands in the mouth. The 1926 expedition to Komodo served as the inspiration for King Kong, in which a similar expedition to a foreign island reveals prehistoric megafauna.

For centuries, tales of large “ape-men” in East Africa have captivated explorers and natives alike. Numerous tribes have legends of massive, hairy creatures that would kidnap and eat humans, overpowering them with their ferocity and strength. The creatures go by many names, among them ngila, ngagi, and enge-ena. In the sixteenth century, English explorer Andrew Battel spoke of man-like apes that would visit his campfire at night, and in 1860, explorer Du Chaillu wrote of violent, bloodthirsty forest monsters. Up until the twentieth century, many of these tales were ignored or discounted. In 1902, German officer Captain Robert von Beringe shot one of these “man-apes” in the Virunga region of Rwanda. Bringing it back to Europe with him, he introduced the world to a new species of ape: the mountain gorilla (Gorilla Gorilla Beringe, in Beringe’s honor). Today, mountain gorillas are known to be communal, largely docile herbivores that live in the Virunga Mountains in Central Africa, and in Bwindi National Park in Uganda. Mountain gorillas are threatened by poaching and civil unrest, elusive and often unseen in their activities. No more than 400 remain in the wild today. One of the earliest written accounts of gorillas may come from Hanno the Navigator, a Carthaginian explorer who documented his travels along the African coast in 500 B.C. Hanno describes a tribe of “gorillae”, roughly meaning “hairy people”. It is unknown whether Hanno referred to gorillas, another species of ape, or humans. Nevertheless, his description served as the inspiration for the modern name “gorilla”.

Central African tribes and ancient Egyptians described and depicted a bizarre creature for centuries, colloquially dubbed the “African unicorn” by Europeans. It is known locally by such names as the Atti, or the O’api, resembling a cross between a zebra, a donkey and a giraffe. Despite descriptions from explorers and even skins, Western science rejected the existence of such a creature, viewing it as nothing more than a fantastical chimera of real animals. Determined expeditions uncovered nothing, and it would seem the “African unicorn” was just as mythical as its namesake. This changed in 1901 when Sir Harry Johnston, the British governor of Uganda, obtained pieces of striped skin and even a skull of the legendary beast. Through this evidence and the eventual capture of a live specimen, the animal now known as the okapi (okapia johnstoni) was recognized by mainstream science. The okapi is no less unusual today: it is the only living relative of the giraffe, sharing a similar body structure and its characteristic long blue tongue. However, the markings on its back legs resemble that of a zebra’s stripes. Okapis are solitary creatures that remain captivating to scientists; although not endangered, there is still much to learn about their habits and lifestyle. The okapi was the symbol of the now defunct International Society of Cryptozoology, and remains a persisting icon of Cryptozoology to this day.

Tales of enormous squids have circulated throughout the world since ancient times. Aristotle and Pliny the Elder both described such monsters; legends such as the Lusca (Caribbean), Scylla (Ancient Greece), and the sea monk (Medieval Europe) all describe a bizarre, often dangerous nautical creature. Perhaps the most famous legendary squid is the Norse Kraken, a monstrous, tentacled beast as large as an island that devoured ships whole. Prior to the 1870s, scientific opinion held such creatures as nothing more than ridiculous myths, on par with mermaids or sea serpents. Despite this, investigations into the existence of the legendary Kraken took place as early as the 1840s. Danish zoologist Johan Japetus Streensup methodically researched and catalogued giant squid sightings and strandings, eventually examining a beached corpse and designating the beast’s scientific name: Architeuthis. Even so, fellow scientists remained skeptical and continued to dismiss accounts. In the 1870s, the skepticism stopped as several carcasses were beached in Labrador and Newfoundland. Tentacles and complete corpses revealed to the scientific world that the giant squid was indeed real. Today, this creature remains just as mysterious and rare. Typically living at great depths, giant squid sightings are uncommon and often undocumented. For a century, scientists dutifully attempted to observe it in its natural habitat, but failed. Only in 2004 were a group of Japanese scientists able to capture a live giant squid on camera, taking 500 automatic photographs before the creature swam back into the blackness. Many questions remain concerning the giant squid. Very little is known about its habits and lifestyle, and it is still unknown how large a giant squid can grow. The largest specimens are between 30 and 40 feet long, weighing over 100 pounds. However, its close relative, the Colossal Squid, may grow to much greater sizes, as evidenced by the size of sucker marks on sperm whales. To this day, the giant squid remains a legendary example of how fantastic animals on earth can be.

The existence of the giant panda has never been disputed by the scientific community; therefore, it has never been a true cryptid. However, its story offers a valuable lesson to believers and skeptics alike on the merits of cryptozoological research. The giant panda became known to Western science in 1869, when a dead specimen was presented to French naturalist Perè Armand David. In the following years, museums eagerly sent off expeditions to obtain pandas for their exhibits. However, as anthropologist George Agogino writes, “From 1869 until 1929, a period of sixty years, a dozen well-staffed and well-equipped professional zoological collecting teams unsuccessfully sought an animal the size of a small bear in a restricted area . . . The giant panda lives in the same general area and at the same general elevation as the Yeti, yet this animal has remained hidden for over sixty years.” In 1929, Theodore and Kermit Roosevelt finally killed a giant panda after six decades of elusion and fruitless searching. This historical episode of zoology should send a strong message that nature still has many mysteries to yield, and that our efforts to uncover them can be a daunting, but worthwhile, task.