Scientists also encountered many weird firsts. From virgin births to living for centuries, sharks are revealing addictive facts about themselves. They also come with dangerous myths, some of which might finally destroy these ancient wonders.

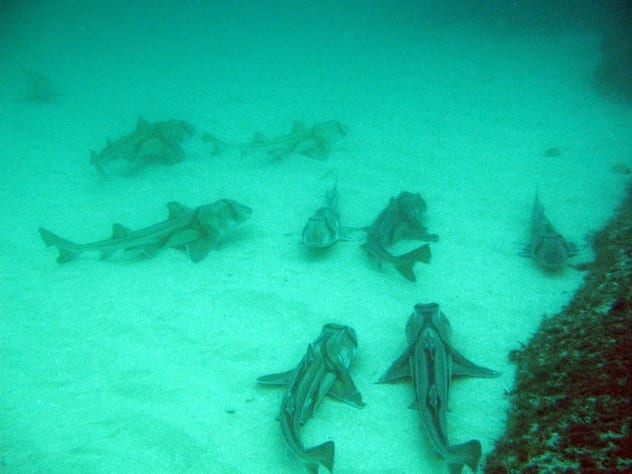

10 Baby Scans For Whale Sharks

Conducting an ultrasound is not usually dangerous to the doctor. However, a hairy first happened in 2018. The ladies in question were the world’s biggest sharks.[1] Whale sharks are not predators, but they easily dwarf a bus. Despite their immense size, whale sharks tend to disappear. They regularly scoot 1,829 meters (6,000 ft) deep and embark on some mind-bending treks. This makes it difficult to understand their mysterious breeding cycle. Knowing when and where they breed could protect the endangered species. Luckily, a group of whale sharks hung around the Galapagos Islands, and biologists scanned 21 females. It took two weeks of waterproofing equipment, keeping up with the moving giants, and trying to image the other side their 25-centimeter-thick (10 in) skin. None were pregnant, nor did their reproduction biology become clear. However, invaluable data was gathered, including things that had never been seen before, like ovaries with follicles. Interestingly, the study also revealed a quirky response—the sharks sped up whenever the scan was activated but not when they were tagged. This suggested that the ultrasound was audible to the females.

9 First Omnivorous Shark

A 2018 study surprised the socks off experts. Sharks tend to bring mental images of bloody raw meat consumption. For decades, researchers knew that one common species, the bonnethead, gulped sea grass in large amounts.[2] Despite this, it was assumed that the sharks accidentally ingested the plants while hunting for prey in sea grass meadows. However, when grass makes up 62 percent of an animal’s stomach contents, sharper scientists began to wonder. Despite being believed to give sharks no nutrition, it blocked the stomach from holding foods that did. To get to the bottom of the stalk-munching predators, a special tank was created. After homing five bonnetheads within, the sharks were fed sea grass with a special chemical signature. Their diet consisted of 90 percent grass and ten percent squid. After three weeks, the sharks were fatter. This encouraging gain needed scientific confirmation, and that’s where the chemical tracer helped. It showed that the bonnetheads absorbed over half the grass’s nutrients. This made them the first recorded omnivorous shark species.

8 Ancient Shark Attack

The Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County owns the fossil skeleton of a flying reptile.[3] This pteranodon has a shark tooth in its neck. Several visitors thought the combination did not suggest an ancient killing but two fossils that were accidentally pushed together. This prompted researchers to re-examine the reptile. The unknown species of pteranodon was found in Kansas. It lived roughly 85 million years ago, when the region was an ocean. The shark species was Cretoxyrhina mantelli, an extinct customer that—in this case—was gauged to reach about 2.5 meters (8 ft) in length. The study found that the snapper was forced deeply underneath a vertebra’s protrusions. Clearly, a powerful jaw was behind the bite. It was unlikely that a current sloshed a loose tooth into the reptile’s carcass before they fossilized together. How the bite occurred remains unclear. The shark could have scavenged on the floating body of the pteranodon. Modern sharks are also known to slam into seabirds with great speed. This could mean that the living pteranodon was bobbing on the waves, like a seabird, when the massive C. mantelli crashed into it.

7 Jumping Giants

In 2018, a study compared great white sharks and basking sharks. At first, they seem to have nothing in common. The great white is a fierce predator that scares people and seals the world over. The basking shark is basically a giant sieve, placidly searching for tiny plankton.[4] Observations of hundreds of basking sharks near Ireland found something surprising: The slow giants, growing up to 10 meters (33 ft) long, could leap. Video footage captured the animals breaching as high and fast as great whites. This crushed the long-held belief that they were placid, drifting behemoths. Watch this video on YouTube Video analysis and recording devices attached to one shark showed just how wrong that view was. This individual took nine seconds and ten tail beats to zoom to the surface from a depth of 28 meters (92 ft). It breached at nearly 90 degrees, cleared 1.2 meters (4 ft) above the waves, and was in the air for about a second. To put all those numbers into perspective, one researcher aptly said, “It’s a bit like discovering cows are as fast as wolves.”

6 The Florida Survivor

In 2014, divers at a popular Florida spot came upon a gruesome sight. A male lemon shark had been pierced by a metal fish stringer.[5] This piece of equipment is used by anglers to keep their catch on a line. The shark probably swallowed such a catch along with the stringer, which stabbed through the animal’s stomach and skin. The lemon shark not only survived, but he gave scientists a first-time view of how sharks expel dangerous objects in a way never imagined. Over the following 14 months, the male was spotted 12 times. On every occasion, the metal’s progress out of the body became more pronounced. At the beginning, just a sharp point protruded. Eventually, the shaft became more visible, and by the time it was spotted in 2016, the object was gone. A scar had replaced the wound. The lemon shark survived over 435 days with a deep hole, avoided infection, and likely overcame severe damage to its stomach and liver. Sharks are known for quick recoveries. This case, however, provided the first evidence that their incredible healing abilities occur internally as well.

5 Sharks Get Cancer

There is a hopeful rumor floating about that sharks cannot get cancer.[6] Unfortunately, this is not true. In fact, the scientific world has known for over 150 years that sharks can also develop the devastating disease. Cancer has been recorded in 23 shark species, and in 2013, the first case surfaced in great whites. The individual in question was photographed in Australian waters. It bore a massive tumor on its mouth, measuring 30 centimeters (12 in) long and wide. The persistent misconception that sharks can’t get cancer is driven by the shark cartilage industry, which promotes related products as an anti-cancer treatment. This industry, together with shark finning, is part of the reason why around 100 million sharks are slaughtered each year. No study has proven that shark cartilage prevents or cures cancer. Scientists are also convinced that even if sharks were miraculously cancer-resistant, consuming their tissues would not fight off the disease in humans. The myth is also dangerous to cancer patients, who forgo traditional treatments, which can help them, in favor of ineffective shark products.

4 Right-Handed Sharks

In 2018, scientists asked the question: Does global warming make sharks left-handed or right-handed? This refers to direction preference and not fin usage. Australian researchers collected two dozen Port Jackson shark eggs and placed half in a tank warmed to the temperature of the bay they were scooped from, 20.6 degrees Celsius (69.1 °F). The remaining 12 were incubated in a tank that simulated temperatures predicted near the century’s end, should climate change continue at its current pace. This aquarium was gradually heated to 23.6 degrees Celsius (74.5 °F). Half of the pups that hatched in the warmer tank died within a month.[7] The rest were tested for “handedness.” To reach food, they had to choose a branch on a Y-shaped partition. The “bay” group showed no preference, but those from the warmer tank had a marked tendency to go right. This automatic behavior could be an incredible adaptation. Warming water increases energy spending; the sharks grow and metabolize faster. This drain could cause smaller brains. Automatically doing something, like always turning right when faced with a hurdle, sidesteps limited mental capacity.

3 Pups Without A Father

Leonie the zebra shark cruises around the Reef HQ Aquarium in Australia.[8] For a few years, she and her mate had several litters. When they were separated in 2012, her keepers rationally assumed there would be no more reproduction. In 2016, however, Leonie laid three eggs that hatched. The triplets were thought to be the result of stored sperm. However, DNA tests matched none of the males (whom she had no contact with for years). The pups only carried their mother’s cells. Asexual reproduction had been unknown in zebra sharks beforehand. This also makes Leonie the first recorded shark to switch from sexual reproduction with a partner to the no-dad-required version, called parthenogenesis. In parthenogenesis, a certain type of egg cell essentially acts like sperm. Although more common in invertebrates and plants, cases of vertebrates that normally reproduce with partners doing so asexually are on the increase. Animals like Komodo dragons, vipers, and even chickens now sometimes produce offspring without males. Strange as it seems, this is good news for zebra sharks, which are listed as an endangered species.

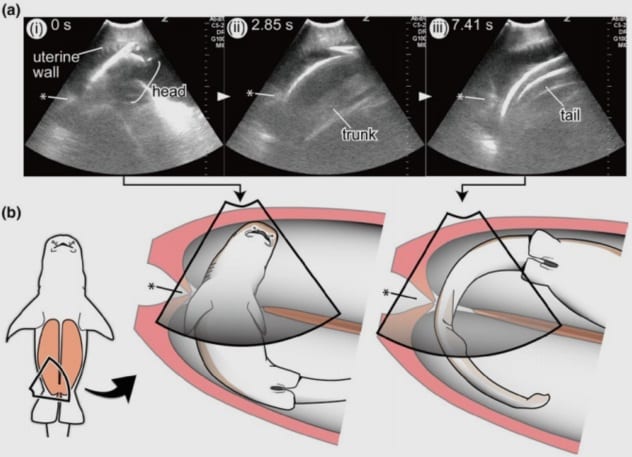

2 Uterus-Switching Pups

Sharks radiate independence. In 2018, this tendency manifested in a remarkable way. It is well-known that sharks consume their litter mates in utero (or in this case, the unfertilized eggs).[9] During an underwater ultrasound on a captive tawny nurse shark, the scan captured this pup-eat-pup behavior. What stunned researchers was how it happened. The shark has two uteri. Showing that independent spirit, the babies slithered from one womb to the other to snack on their unfertilized siblings. Not only does this make the tawny nurse shark very peculiar, but it also sheds light on a 1993 documentary. A camera crew found a pregnant sand tiger shark. They noticed that her pups switched wombs through a hole in her side. Since it was not entirely natural (the hole was a wound), it did not prove that sand tigers always did this. However, that was the first time the bizarre uterus-switching was recorded. Tawny pups also peek. In a remarkable finding, unborn embryos sometimes stick their heads out from the mom’s cervix and experience direct contact with the watery world outside.

1 500-Year-Old Sharks

If there were an award for ultimate weirdness, the honor would go to the Greenland shark. At first sight, it appears dull and unremarkable. But its longevity is something out of a science fiction novel. In 2016, the first attempt was made to scientifically gauge this species’s life span. Twenty-eight of the slow-moving Arctic sharks were harvested.[10] The group was already dead from accidental deaths caused by fishing and scientific vessels. One of the first things that became obvious was that the sharks grow slowly. The fact that some adults reach 4.9 meters (16 ft), suggested long lives. To narrow down an estimate, researchers used radiocarbon dating. The “body part” they chose were eye proteins created at birth. Interestingly, radiocarbon dating usually comes with something called the “bomb pulse.” This signature was caused by the nuclear testing of the 1950s and 1960s, which released a massive amount of radiocarbon. The sharks in the study had the pulse, which helped refine their growth rate. Incredibly, some sharks could have been over 500 years old. Even more mind-bending, they only reached sexual maturity at 150. Read More: Facebook Smashwords HubPages