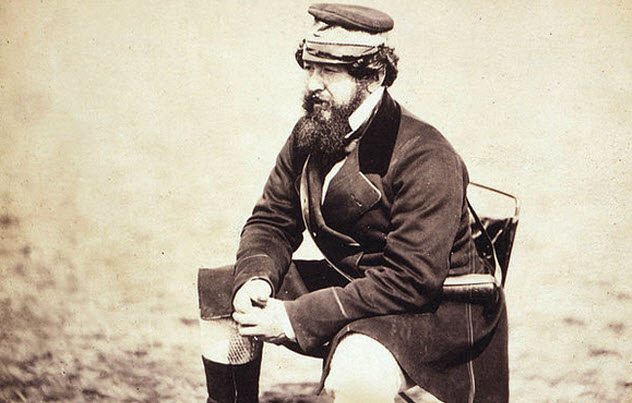

10 William Howard Russell Brings Home The Horrors Of War

William Howard Russell was the first dedicated war reporter in history. A hard-drinking, hard-living Irishman, Russell was dispatched by The Times of London to cover the Crimean War, an epic 1853 punch-up between Russia, Britain, France, Sardinia, and the Ottomans that killed nearly a million people. While there, Russell did the expected stuff like get drunk, write up the Charge of the Light Brigade, and get even drunker. But he also did some less expected stuff. Stuff that annoyed the British establishment back home. Stuff that involved exposing the horrific conditions that wounded soldiers were recuperating in. Russell wrote of how “men (died) without the least effort being made to save them” and how “the sick appear to be tended by the sick, and the dying by the dying.” The army hated these reports so much that they tried to scare him off, at one point destroying his lodgings.[1] Yet Russell kept filing his reports and finally made a difference. The public backlash from his stories was so great that the British army was forced to start treating its wounded vets better, paving the way for hospital reforms ushered in by fellow Crimea veteran Florence Nightingale.

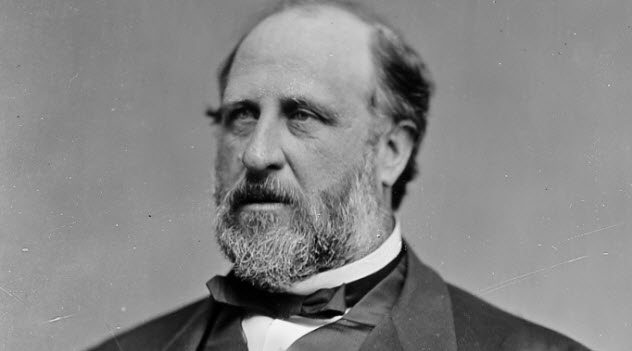

9 The New York Times Takes Down Boss Tweed

If you think modern politicians have their noses in the trough, be glad you didn’t live in the days of Boss Tweed. The Democratic senator and leader of New York City’s Tammany Hall was like a cartoonist’s idea of corruption. Tweed controlled New York City’s legislature and much of the state beyond. He and his cronies pocketed somewhere in the region of $1–$4 billion in today’s money, only slightly less than Ferdinand Marcos managed to steal as dictator of the Philippines. Tweed ran an extortion racket out of a nonexistent law firm, used Irish street gangs to intimidate opponents, and lived the high life of champagne and oysters while others starved. The thing that eventually stopped his petty reign? The New York Times. The New York Times of the 1870s was co-run by George Jones. He hated Tweed and made it his paper’s mission to bring the fat cat crashing down. In 1871, Jones managed to get hold of minute breakdowns of Boss Tweed’s personal spending plans for public money.[2] Tweed’s gang offered Jones the equivalent of $100 million in today’s dollars to keep quiet. Jones refused and published, his articles eventually helping to get Tweed jailed in 1873.

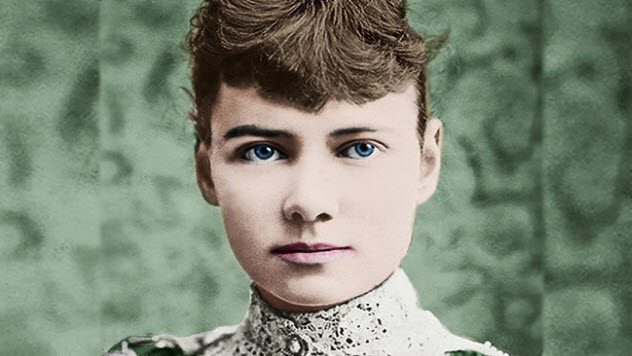

8 Nellie Bly’s Undercover Reports From The Madhouse

Using “madhouse” in the title of this entry might not be particularly PC. But there’s no other way to describe what reporter Nellie Bly found at Blackwell’s Asylum in 1887. After getting herself committed, she spent 10 days living undercover among mental patients. She discovered a place that took in sane people and slowly turned them mad. The inmates whom Bly encountered were mostly poor with nowhere else to go. That didn’t stop the nurses from treating them like crazed devils in a Hieronymus Bosch painting. Bly witnessed nurses beating and choking inmates and pulling out chunks of their hair.[3] They also had an excellent line in banal cruelty. One of the tasks assigned to patients was to spend several hours each day sitting on a hard wooden bench, staring straight ahead and not talking, moving, or sleeping. As Bly wrote, it was enough to send a sane person crazy. When her story came out, Blackwell’s went to insane lengths to cover up the abuse. They discharged patients whom Bly had interviewed, hid evidence, and generally tried to weasel out of it. It didn’t work. A grand jury investigation wound up changing mental health care in America forever.

7 Ida Tarbell Takes On Standard Oil’s Monopoly (And Wins)

If you ever find yourself in possession of a time machine, make sure you don’t jump back to 1872 and annoy Ida Tarbell. The daughter of an independent oilman, Tarbell was just 14 when she watched John D. Rockefeller Sr. crush her father’s business after he refused to sell. Almost 30 years later, she wrote a 19-part hit job on Rockefeller for McClure’s Magazine. In it, she forensically laid out the evidence that Rockefeller’s Standard Oil was running its monopoly like a bunch of mobsters. Through long interviews, hundreds of hours of reading records, and hundreds more of learning about the oil business, Tarbell revealed breathtaking acts of espionage, collusion, breaking of antitrust laws, and general douchebaggery.[4] She demonstrated that Rockefeller was in cahoots with railroad barons to snuff out independent oil producers and create a mass monopoly. Over three decades after he destroyed her father’s company, Rockefeller was forced to watch as Tarbell’s story led to his beloved Standard Oil being smashed up by the Supreme Court.

6 The Telegraph Does The Entire British Parliament For Fraud

Not all great journalistic campaigns came in the distant past. The Telegraph’s 2009 attack on the British establishment was as incendiary as anything in the Victorian era. The paper managed to get hold of a full list of all expenses that British MPs had claimed from taxpayers’ money. The details came straight from the Boss Tweed playbook of fleecing your country. The Telegraph uncovered MPs who’d charged parliament for flat-screen TVs, jellied eels, gardening work, home cinema systems, and antique rugs. There were claims for silk cushions, a brand-new house for an MP’s ducks, and (memorably) a claim from an MP who lived in a castle for having his moat cleaned. The worst of the scandal involved something known as second home “flipping.” In the UK, MPs are entitled to claim against their second home in London so that they don’t have to commute from Cornwall or the Inaccessible Islands every day. The Telegraph found that MPs would habitually flip which home was the “second” one, allowing them to charge taxpayers eye-watering sums for mortgage payments and renovations on both buildings.[5] Following the investigation, eight MPs or peers were convicted of fraud and jailed. Dozens more repaid the sums owed. The swamp may not have been completely drained, but it certainly got a good kicking.

5 Seymour Hersh Exposes The My Lai Massacre

The My Lai Massacre is one of those awkward historical moments when you discover that your team is kind of the bad guys. In 1968, US soldiers under the command of First Lieutenant William L. Calley went on a search-and-destroy mission for the Vietcong in a village known as “Pinkville.” They didn’t find many communists, but they sure as hell found civilians. The soldiers massacred fleeing villagers and then dragged the rest into a ditch, where Calley ordered his men to finish them off. A minimum of 109 people died, perhaps as many as 500.[6] There was an investigation, but it was fronted by Calley’s own battalion who, unsurprisingly, found no evidence of wrongdoing. When a second investigation was launched, journalist Seymour Hersh was tipped off. After interviewing Calley’s defense team, he published an account of what he called the “murder.” US society exploded. The Vietnam War was already unpopular, but Hersh’s report killed stone-dead what little support remained. It led to the conviction of Calley for murder, although he was paroled less than five years after starting his supposed life sentence. For his part, Calley only apologized for the massacre 40 years after it happened.

4 The Sunday Times Exposes The Drug That Crippled Children

Thalidomide was a medical disaster. Marketed as a sedative for pregnant women, it had the horrible side effect of deforming fetuses, leading to babies being born with missing limbs. Over 10,000 affected children were born worldwide, with West Germany, the UK, Canada, Australia, and Japan among the worst affected. By 1961, thalidomide’s developers already knew it was dangerous and had withdrawn it from the market. Their subsidiaries had even offered compensation in the UK to the tune of £3.25 million. For Sunday Times editor Harold Evans, this wasn’t just an inadequate amount to share among 370 victims. It was a slap in the face for families dealing with their children’s disabilities. From 1972–76, his paper ran a ferocious campaign to bring thalidomide’s UK distributor, Distillers, to account. It worked better than anyone had expected.[7] Faced with constant stories of affected families and disabled kids, shareholders at Distillers revolted. The company was forced to increase its compensation tenfold, yet The Sunday Times still wasn’t done. They chased Distillers to the European Court, eventually getting them to admit that no proper trials had been done. The campaign changed the way that new drugs are tested and marketed in both Britain and other parts of the world.

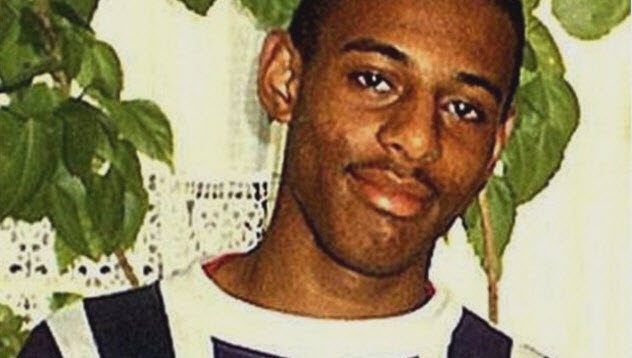

3 The Daily Mail Demands Justice For Stephen Lawrence

The Daily Mail isn’t the greatest tabloid. But despite some questionable stories, even the Daily Mail can occasionally do remarkable good. In 1997, the paper’s editor, Paul Dacre, went after the murderers of black teenager Stephen Lawrence. Dacre didn’t stop until justice had been done. Lawrence was killed by five white youths on a London street in 1993. Racist officers working for the Metropolitan Police lied about and bungled the investigation, ensuring that the killers went free. Something about this seemed to rile Dacre. On Valentine’s Day 1997, he plastered the paper’s front page with pictures of the five youths under the headline “MURDERERS.” Beneath, he challenged, “If we are wrong . . . sue us.”[8] The paper’s campaign ignited public interest in the murder. It led to a public inquiry being held into racism in the Metropolitan Police Force. It saw the end of Britain’s double jeopardy laws. In 2011, two of the five youths were finally jailed for life. As of 2017, the Daily Mail is still campaigning to make the remaining three face justice.

2 A Magazine You’ve Never Heard Of Breaks The Iran-Contra Story

It’s the biggest White House scandal that didn’t force a president to resign (Watergate) or only emerge after his death (President Harding’s “Teapot Dome” scandal). Iran-Contra saw the Reagan administration break its own laws to sell arms to Iran and then use the proceeds to fund the violent Contra guerrilla movement in Nicaragua—a move that violated the Boland Amendment passed by Congress. When the scandal was revealed, it rocked Washington to its very core. Fourteen members of Reagan’s staff were indicted, with 11 being convicted. So who broke this incredible story? Al-Shiraa, a Lebanese weekly newspaper that no one had ever heard of.[9] The arms sales to Iran were done in the hope of freeing American hostages. These hostages were held in Lebanon, then in the grip of a deadly civil war. Al-Shiraa was able to uncover these trades and break the story. Their expose triggered an investigation by Attorney General Edwin Meese, who discovered the funds from these arms sales were missing. He managed to trace them to Nicaragua, and the entire Iran-Contra affair was suddenly exposed. It goes to show even journalists toiling away at the most obscure title really can make a difference.

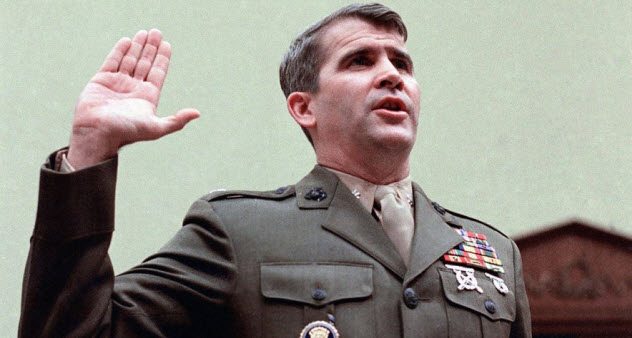

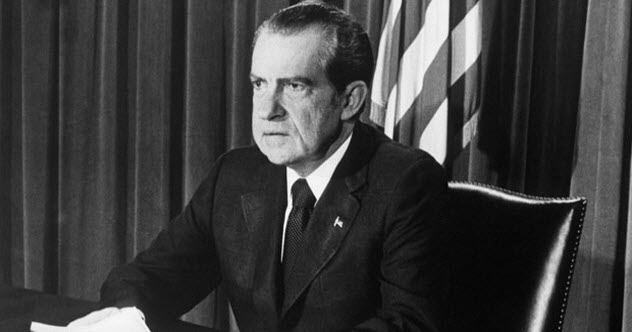

1 Watergate

Be honest. Did you expect anything else to take the No. 1 spot? Watergate remains the biggest scandal in US history. After his goons were spotted burglarizing the offices of the Democratic Party at the Watergate Hotel, Richard Nixon attempted a far-reaching cover-up that saw him silencing witnesses and pressuring investigators to drop the case. It eventually led to Nixon losing the confidence of his party and Congress and suddenly resigning to avoid impeachment and a possible criminal trial. That we know of this at all is mainly thanks to two men: Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein.[10] In 1972, the pair were at The Washington Post when the burglary story came to their attention. Rather than quickly write it up and move on, they smelled something fishy and decided to keep digging. And digging. And digging. By the time they finally stopped, it was 1975 and the United States had changed forever. Woodward and Bernstein didn’t just use their positions as journalists to speak truth to power. They went out, took power by the scruff of its neck, and beat it within half-an-inch of its life. They socked it to elites who thought they could get away with playing by different rules, and they made sure the lesson stuck. The press may not always be popular, but stories like that of Woodward and Bernstein—and everyone else on this list—show just why we’ll always need them.