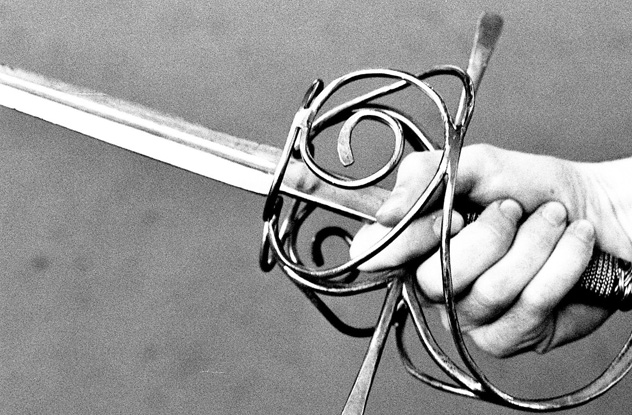

10Rapiers Are Light And Delicate

Every decade has its own Three Musketeers movie and quite possibly several. This has ensured that the rapier is well enshrined in all our heads as the weapon of choice for foppish, yet deadly, European aristocrats. In fact, most rapiers weigh between 1–1.4 kilograms (2–3 lb), the same as surviving historical longswords. Many rapiers have narrower blades than other renaissance swords, but they are also longer, some 107 centimeters (42 in). The reason we think of rapiers as particularly light is probably because we confuse them with other thrust-centric swords like 18th-century small swords or even modern epees.

9Two-Handed Medieval And Renaissance Swords Weighed Over A Dozen Pounds

This myth is the inverse to the above. While medieval longswords weighed about the same as a rapier, in the Renaissance there were two-handed swords that were heavier. However, these “greatswords” still only ranged from 2–4 kilograms (4–7 lb). Greatswords were often employed both on the battlefield and in self-defense. 17th-century accounts note that the greatsword is particularly suited for fending off multiple opponents. The mistake again arises when two similar types of swords are confused. There are surviving Renaissance swords that are indeed very heavy, but they are execution and ceremonial swords, not battlefield ones. Even those types of sword often weigh about 5 kilograms (10 lb) and only a few extreme examples go any higher.

8Gunpowder Made Swords Obsolete

This is the misconception on this list that most approaches truth. Gunpowder did indeed put bladed weapons out of commission, but it took much longer than you might think. In the early gunpowder period, the inaccuracy and slowness of loading most firearms meant that swords remained a viable weapon. By the mid-19th century, weapons like revolvers and mass-produced breech-loading rifles certainly made wielding a sword in a combat a dicey proposition. But most European powers were fighting colonial wars against opponents who often only had access to outdated firearms in limited amounts. For example, in 1898, the Dutch issued their soldiers in Indonesia a short cutlass suited to jungle fighting. It was only really in World War I that combat with swords ceased to be an expected part of war. Up through the 19th century, saber fencing was a major part of training for officers, as illustrated by the large number of manuals produced for military use.

7Historical Cultures Used Only One Sword Design

In movies, we can generally guess what type of sword a person will use by their ethnicity. A Roman will use a gladius, a Scotsman a claymore, and a Japanese person a katana. But many such iconic weapons were only used in certain periods and were often used alongside other weapons, depending on context. The Roman gladius was adopted in the third century BC from the Celtiberians in Spain. Later Roman armies from the late second to the third century onward replaced the gladius with a longer sword, the spatha. The famous Japanese katana was itself a replacement for various earlier sword designs, including one very similar to the Chinese jian, the chokutu. Even during the height of the katana’s popularity, alternate swords like the longer nodachi were still used.

6Only High-Status People Used Swords

In the early Middle Ages, swords were expensive and were a sign of high status. Ordinary soldiers primarily used spears. Law codes from ninth-century Europe give the value of a sword with scabbard as 7 solidi (a type of gold coin), the same as a good horse. We know from wills that particularly fine swords could be worth much more. In the later Middle Ages, swords were a bit like cars today. You could get a cheap but serviceable version or an extremely expensive one. A cheap sword in the 1340s might cost around 6 pence, the same as a day’s wages for a mounted archer serving in the English army in France at the same time. Manuscript illustrations show that not only was a cheap sword within reach for a common soldier, but many archers wore them as secondary weapons. Many people know the katana as the symbol of the samurai, and indeed in the Edo Period (1603–1868), it was the legal prerogative of the samurai class. However, before the long peace of the Edo Period, sword ownership among the peasantry was common enough that Toyotomi Hideyoshi issued an edict requiring all farmers to turn in their weapons to prevent peasant uprisings.

5You Can Cut A Sword In Two

This assertion generally comes in two forms. One is based on thinking rapiers are delicate so can be snapped by a bigger sword. In reality, tests done with reproduction weapons find that with even repeated striking, rapiers do not snap into two pieces. The second variety comes from the mythology surrounding katanas. While the katana is a superb cutting weapon, it cannot achieve the physically impossible. The Mythbusters tested one katana cutting at another, and even a robot arm could not cut a blade in two.

4Swords Will Slice At The Slightest Touch

There’s no doubt that swords are sharp, but we often misunderstand exactly what it takes to cut with a sword. Cutting has to be done with the proper technique and body mechanics. Cutting doesn’t stop after the sword has contacted the target. The swordsman should continue to pull the blow through, slicing the target. Because motion is essential for a sword to slice, it is possible to actually grip the blade of a sharp sword with bare hands. Indeed, many medieval and renaissance fencing manuals show this being done to gain leverage and thrusting power in certain situations.

3There Is Such A Thing As A Superior Sword

Swords, like any other tool or weapons, are influenced by the function they are supposed to perform. In turn, the function a sword is designed for is a result of the cultural and technical context of its time. For example, sabers are excellent weapons for light cavalry facing lightly armored opponents, but they would quickly be stymied by the sort of plate armor common in 15th- and 16th-century Europe. It is no surprise that, although sabers are known earlier, they reached the height of their popularity and were most widespread in 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, after effective gunpowder weapons reduced the appeal of heavy armor. Swords not only varied by time period but also by their social context. 19th-century epees were only ever used in duels with other epees, and that influenced their evolution without outside influence.

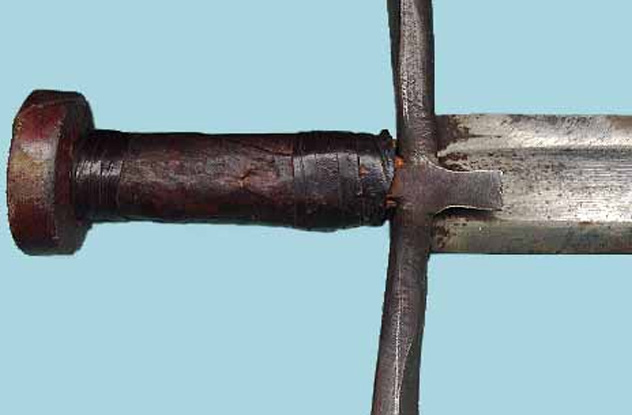

2Sudanese Kaskara Are Descended From ‘Crusader Swords’

When 19th-century European imperialists came to Sudan, they found swords in use that superficially resembled medieval European swords through their straight blades and cruciform hilts. This similarity led people to believe that the kaskara was a descendant of medieval European weapons. Since several of the later crusades had targeted Egypt it was presumed that this was how the kaskara’s ancestors came to North Africa. However, straight-bladed weapons with cross guards were originally much more common across North Africa and the Middle East, being displaced in popularity by curved slashing weapons. It is most likely that the kaskara is a survival of these forms.

1Bronze Swords Are Soft

When bronze was replaced by iron as a weapon for combat, convenience and cheapness had a lot to do with it. Iron is a naturally occurring element, rather than an alloy and is rather abundant. Iron does melt at a higher temperature than bronze and is harder to smelt, but once this technical problem was resolved, iron won out on the basis of its cheapness, rather than as a result of greater hardness or suitability for combat. Many early iron products were no harder than their bronze counter parts. Studies of surviving central European bronze swords conclude that bronze swords were indeed functional as practical weapons. Jim Lyons is a student passionate about history, speculative fiction, and traditional music.