Fossils and mummies give unprecedented insight into extinct species, geological features, and modern horse biology. Even horse art can sometimes add surprising historical details.

10 Clues To Tibetan Plateau

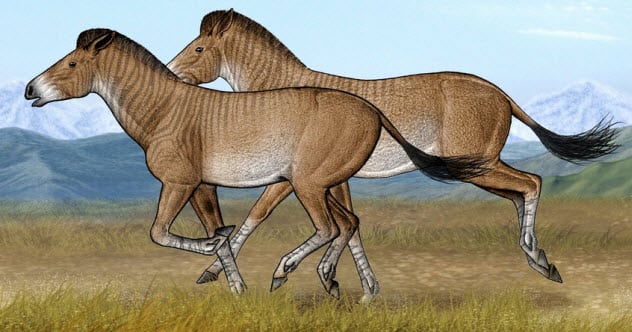

Ancient animal bones can provide a kind of geographical report about the area in which they were found. In this case, a three-toed horse has added details to the youngest and highest plateau on Earth. Today, its average elevation stands around 4,500 meters (14,800 ft). Scholars have always argued about when the so-called Tibetan plateau rose to this point and, more specifically, whether the landscape was higher or lower about five million years ago. In 2012, a plateau skeleton from that period threw light on the matter. The Zanda horse (Hipparion zandaense) looked more like a tiny zebra with triple toes than a thoroughbred. Its feet, teeth, and long legs all indicated an animal that grazed and sprinted across open grassland. This already suggested that the area was above the tree lines. Chemicals from the skeleton identified a diet similar to what wild asses enjoy on the Tibetan plateau today. These grasses are adapted to the kind of cold temperatures characteristic of great heights. Using all these clues, it was determined that the Zanda Basin was already at the region’s current elevation when the horse died.[1]

9 Rare Hipposandals

In 2018, a volunteer offered to help with excavations at an ancient landmark. While digging in a ditch at the Roman fort Vindolanda in Northumberland, the volunteer found something exceedingly scarce. Hipposandals were early Roman “horseshoes” made of metal that were meant to protect the hooves. They were a bit more elaborate than today’s crescent-shape shoe. What made the find an archaeologist’s dream was that the set of four hipposandals was complete and in an exceptional state of preservation. Even the ribbing underneath—to prevent the animal from losing traction and skidding—could still be seen. One of the sandals showed a hairline fracture, which could be the answer to why a perfectly good set was discarded. Maybe the owner decided to chuck away the whole lot when he noticed one was cracked. Forged between AD 140–180, these iron devices were found in a ditch that was originally a trash site. It was covered with new clay foundations when another fort was built, preserving the shoes and countless more Roman treasures.[2]

8 Unknown Roman-German Peace

The Roman Empire once collected vast territories, and one such region was modern-day Germany. Scholars always thought that the Romans restricted involvement with the locals to the occasional military raid. History tells that things got worse for both sides after AD 9 when the Germans slaughtered a much larger Roman army at the Battle of Teutoburg Forest. In 2009, an artifact was discovered that suggested years of peaceful interaction. It was a 2,000-year-old golden horse head. Found inside a well at the German settlement Waldgirmes, the 25-kilogram (55 lb) head was a fragment of a statue. The intact sculpture, that of a horse and the Roman emperor Augustus, once stood at the village marketplace. This prompted a closer look at Waldgirmes, which revealed that Romans had lived alongside Germans. The site had no military barracks to indicate a forceful occupancy. Instead, the surprisingly advanced town had Roman homes, ceramics, workshops, and a forum (the marketplace).[3] The Teutoburg battle brought an end to many German settlements, including Waldgirmes. Within years, tensions boiled over and Romans burned Waldgirmes to the ground.

7 The Utah Specimen

Horses survived in North America for millions of years. Around 11,000 years ago, they became extinct. Only several millennia later did the first equestrian hooves land again on North American soil when the animals arrived with the Europeans. An exceptionally rare thing to find in Utah is the remains of a horse from the original groups before they all died out on the continent. In 2017, that was exactly what a family found in their backyard. Perhaps due to the scarcity and the fact that the area used to be farmland, the remains were assumed to be a cow’s skeleton. However, the creature was small, about the size of a Shetland pony.[4] When an expert arrived, the animal was identified as a horse from the last ice age that had drowned and sunk to the bottom of a lake. There, it remained undisturbed for 16,000 years. Determining the cause of death and gender might be impossible, but it is still considered to be a prize specimen. One day, the species might even be identified. Researchers already know that it was old (due to arthritis of the spine) and that it possibly had cancer (due to a bone growth on one leg).

6 Near East Horses Came Second

Today, horses get all the glory. It is even assumed that people across the world rode them first. However, a skeleton found in 2008 suggested that the first saddle in the Near East went to donkeys. When the skeleton was discovered, its importance became apparent because the donkey’s molars had the same type of damage as those of horses that wear bits. However, no further investigation was conducted into the possibility that this might be the earliest evidence of donkey ridership in the region. Instead, the archaeologists focused on the animal’s journey and death. Apparently, the young animal was part of an Egyptian caravan en route to the ancient city-state of Tell es-Safi. Upon arrival, the donkey was sacrificed to bless the durability of a mudbrick house erected atop it.[5] In 2018, tests dated the donkey to around 2700 BC. This proved that people rode donkeys in the Near East for almost 1,000 years before horses arrived in the area.

5 First Horse Dentists

At first, archaeologists could not explain the odd tooth. Rediscovered in 2018 among the archives of the National Museum of Mongolia, the tooth was crooked and sawed halfway through. The answer only dawned on them when local archaeologists who had experience with traditional horse husbandry were called in. The tooth belonged to a horse which had been ritually sacrificed and buried over 3,000 years ago. Shortly before the animal was killed, the owner attempted to flatten the crooked incisor to lessen the animal’s pain. For whatever reason, the operation was abandoned and the horse met its end. Despite the unsuccessful attempt, this is one of the first recorded cases of veterinary dentistry. In addition, this is a very early look at Mongolian horsemanship, something that would eventually change the history of Eurasia in the 13th century and bring Genghis Khan’s empire to power.[6] As horses became more important to the region, skills that included dentistry were perfected to better take care of the animals. Historians doubt that Genghis Khan’s powerful reign would have happened if it were not for Mongolian horsemanship.

4 An Extinct Foal

Between 30,000–40,000 years ago, a foal died in an area of modern-day Siberia. The two-month-old baby perished in a mysterious way that left little damage to the body. Whether it drowned or died of an illness, the tiny corpse became trapped in permafrost. As time went by, its species—the Lena horse—became extinct, along with many other ice age animals. In 2018, scientists were clambering about in the 100-meter-deep (328 ft) Batagaika crater when they found the foal. The animal is officially the best-preserved specimen of an ancient horse. The mummy, which measured 98 centimeters (39 in) tall at the shoulder, was remarkably intact. Soft tissue, skin, hooves, hairs inside the nostrils, and the tail all survived. Wild horses are still in the region today, but none are genetically related to the Lena species (Equus caballus lenensis) in any way. To find out more about the extinct horse, future tests will look at the foal’s diet and possible cause of death.[7]

3 Prehistoric Pregnant Mare

The Messel Pit site in Germany is known for well-preserved fossils. In 2014, it produced the body of a pregnant mare that died around 47 million years ago. She was in excellent condition and revealed a surprise. It was not the nearly full-term foal, but the way in which it was carried. Researchers did not expect to find nearly identical similarities to modern mares in her reproductive system. Just like today, the prehistoric horse had a crumpled outer uterine wall and a ligament connecting the uterus to the backbone.[8] This does not seem strange until one considers the physical differences. The tiny mare was about as big as a fox terrier and hailed from an evolutionary time when horses still had four toes on their front feet and three on each hind leg. Despite the ancient mare looking very different from modern horses, the find showed that some elements of the equine reproductive system were already in place millions of years ago.

2 The Botai Tamers

Few people realize how hotly scholars debate the subject of who tamed the first horses. The leading theory supports a Bronze Age people called the Yamnaya. It was also assumed that they handed their skills to a much simpler hunter-gatherer group, the Botai from Kazakhstan (3700–3100 BC). However, new genetic tests and horse remains complicate this picture. The earliest signs of horse domestication in Asia come from the Botai, including traces of mare’s milk inside a vessel and a bit-worn tooth. Even so, researchers have argued that the culture had to learn horsemanship elsewhere because they remained hunter-gatherers long after others around them became farmers. In 2018, DNA showed that the Botai were not as incapable as previously believed. It was already known that they were an isolated culture, but tests on ancient Botai individuals showed no Yamnaya DNA. The Yamnaya people had a habit of spreading their genes wherever they went.[9] A lack of Yamnaya heritage around the time the Botai already had mounts strongly suggests that they domesticated horses first. Tests on Botai horses also revealed no link to modern animals, more evidence that the two cultures developed separate domestication with different horse breeds.

1 Ancient Breeders Absolved

Today’s horses reflect many traits influenced by the decisions of ancient breeders. One of them is the limited Y-chromosome pool. Modern stallions all share a similar Y, which led to the belief that early breeders used only a few males. Modern equestrians frown at this bad genetic practice because millennia of inbreeding have left horses with segments called detrimental DNA. In 2016, horse remains were taken from Scythian graves and sites where hundreds of the animals were ritually buried thousands of years ago. The Scythians from Kazakhstan were superb riders and warriors (during the ninth to first centuries BC). When 11 stallions were analyzed from one royal tomb, none were inbred and there was no detrimental DNA. This meant that ancient breeders acted responsibly and used a healthy number of stallions instead of the assumed few. The study also found that the Scythians allowed wild horses to interbreed with their stock. The buildup of detrimental genes and a shrunken male pool happened sometime during the past 2,000 years, long after the existence of the breeders who were blamed.[10] Read More: Facebook Smashwords HubPages