10 British Happy Hour

A British camp once stood near the town of Ramle in Israel. Under the command of General Edmund Allenby, the unit occupied the barracks during a time when combat against the Turks in Palestine was put on hold. Arriving in 1917 during World War I, the British stayed for nine months. In 2017, excavations revealed an unwritten slice of what had gone on there. Inside the camp’s rubbish dump, archaeologists found the usual broken kitchenware and then they saw the bottles. Around 70 percent of the items thrown away by the barracks’ occupants consisted of liquor bottles. Hundreds of whiskey and gin bottles—including some marked Gordon’s Gin and Dewar’s Whisky—turned up. It would appear that the men used the long months of respite to get drunk often.[1] The sheer number of empty containers found at the site suggests that becoming inebriated wasn’t against camp rules. This was a unique find for Israeli archaeologists, and it allowed the first look into how these particular soldiers spent their leisure time.

9 Thousands Of Dog Tags

In 2014, an amateur historian visited a field outside London to hunt for relics. Dan Mackay dedicates much of his time to the history of war, which made his discovery even more special. Right next to a World War II anti-artillery gun, he unearthed over 14,000 dog tags. Issued by the British Army, these may have been among the first to be forged from stainless steel. Dog tags for soldiers were invented before both world conflicts, and vulcanized asbestos fiber was used to make them until 1960. The Mackay tags are individually engraved with the names of British soldiers, but these men never received the tags. Most likely, the plans for the newer ID system were abandoned shortly after commissioning the steel tags. In their void state, the tags were then buried in the field.[2] They were made for individuals belonging to nearly every British regiment from before World War II to afterward. This made it extremely difficult to track down the soldiers’ families, but Mackay’s diligent research into the history of the servicemen is slowly returning some of the tags home.

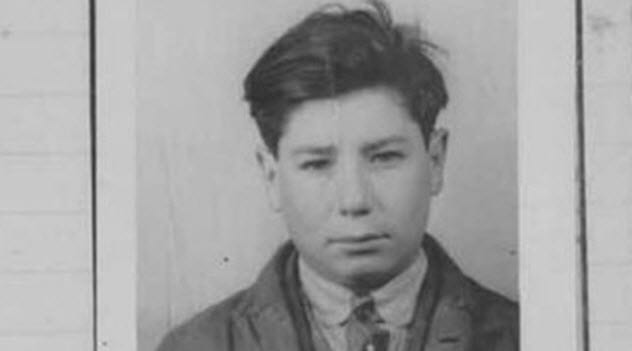

8 The Missing Apprentice

During World War II, a teenager named Frank Le Villio got into trouble with the Nazis. In 1944, the Germans occupied Jersey and confiscated all the vehicles. Le Villio, a mechanic’s apprentice, noticed a motorbike belonging to a German soldier and took it for a joyride. The 19-year-old was arrested and passed between several concentration camps. Historians wanted to know if he had stayed at the notorious Bergen-Belsen and whether he survived. If so, he’d be one of only two British nationals to walk out of there alive. About 50,000 people died there, including Anne Frank. Once it was discovered that Le Villio had traveled to Nottingham after the war, researchers advertised in a local newspaper requesting any information about him. A priest responded and confirmed that the young man had been buried in a mass paupers’ grave in Wilford Cemetery after tuberculosis killed him at age 21.[3] The only proven British survivor of Bergen-Belsen recalled meeting Le Villio but at another location. Further research also provided records for Le Villio’s stay at Neuengamme and Sandbostel (“Belsen in miniature”) but none for Bergen-Belsen.

7 A Secret Weather Station

Near the North Pole, the remains of a wartime German base called Schatzgraber (“Treasure Hunter”) sit on the island of Alexandra Land. Meteorologists stationed there kept the military informed about weather conditions over northern Europe and oceans to the north. Although the World War II base was supposedly secret, its existence was noted in several documents. Schatzgraber was abandoned in 1944, but the icebound island made it impossible to study the entire complex. When the warm winter of 2016 thawed Schatzgraber completely, Russian researchers confirmed what the documents described. For the first time, each building (and its contents) was cataloged. They revealed an ill-fated crew. Starving in winter 1944, the men contracted an agonizing roundworm infestation after undercooking a polar bear. The evacuation plane broke a wheel upon landing and had to wait for a spare to be air-dropped. When the sick men were finally loaded, their leader had to be incapacitated because he’d gone mad.[4] An extensive search revealed the emergency airfield and over 600 artifacts, including tinned food, uniforms, manuals, ammunition, and weapons.

6 The Forest Zones

World War II is among the best-researched conflicts, yet one type of battlefield remained largely ignored. The conflict zones in the forests of Europe came to the attention of geoarchaeologist David Passmore when he couldn’t find any reference to them. In recent years, Passmore took a team and walked through wooded terrain in France, Germany, Belgium, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands. They focused on areas where battles were waged from 1944 to 1945. The locations were identified after gleaning information from academic studies, guidebooks, and the Internet. The team found trenches, bomb craters, and even the ruins of supply depots and foxholes.[5] Of particular interest were the German logistics depots. Incredibly, they revealed the precise locations of the German army’s support network and how it was implemented before Normandy was conquered by the Allies. Furthermore, examining the depots clarified how this network evolved during the Normandy invasion and how it fell to the other side. Passmore’s study of the depots gathered detailed knowledge about where and how soldiers fought in European forests.

5 Training Tunnels

In 2017, the British Army decided to add buildings at Larkhill on Salisbury Plain. Since the site holds historic significance, archaeologists were allowed to first sweep the area. Unexpectedly, they found subterranean tunnels used for training during World War I. The century-old network spanned miles and contained hand grenades (some live), cans of food, and graffiti. The passages were a surprise but not their nature. The area still serves as a military training base and, during World War I, was used to train soldiers for the Western Front. Significantly, during that time, miners and combat engineers received instruction on how to tunnel under enemy trenches and plant explosives. Carved into the chalk walls were over 100 individual graffiti marks.[6] The most insightful were the names of the soldiers who trained there before embarking for the trenches. One was an Australian, Private Lawrence Weathers. He was later awarded the prestigious Victoria Cross after he stormed a German machine gun post and took 180 prisoners in 1918. The archaeological dig at Larkhill is ongoing and remains the biggest investigation into any World War I training tunnel system.

4 The Secret Deal

A German historian blew the lid off a top secret deal when he revealed that The Associated Press (AP) had links with the Third Reich. The subsequent investigation revealed an agreement to exchange war photographs during World War II. Thousands of photos had appeared in the US press with misleading sources such as “supplied by a German agency” and provided by the AP. At first, the agency denied any collusion. But the story of the wartime AP soon unfolded. In 1941, they were kicked out of Germany along with all other foreign news groups. Since both sides remained eager for insider images, a deal was brokered.[7] The AP received censored photographs filled with clever German propaganda. The photos received by the Nazis were also altered by them to cast the US unfavorably in German newspapers. This didn’t sit well with US counterintelligence, which wanted to convict the AP executives involved under the Trading with the Enemy Act. The suggestion was dropped a week later when it came out that the US government had given the AP the thumbs up to start swapping.

3 A Pilot Still In His Plane

Inspired by his son’s homework about World War II, Klaus Kristiansen investigated a field on his farm in Denmark. Klaus’s late grandfather had claimed that a warplane crashed there in 1944. However, there was no indication of it during the 40 years that Klaus had farmed the land. Then in 2017, Klaus and his 14-year-old son, Daniel, listened excitedly as their metal detector began buzzing. At 4–6 meters (13–20 ft) down, they found the plane, a World War II German Messerschmitt. The aircraft was torn into thousands of pieces. Among the fragments were the engine, ammunition, and human bones. Bits of the airman’s clothes surfaced, and his wallet still contained money. Investigators identified the pilot after examining additional items. The man’s initials were etched on his watch, and they matched the name found on a service document and calendar book pulled from the wreckage. The pilot was 19-year-old Hans Wunderlich. His military records showed that he was Bavarian born, unmarried, and childless. The plane is set to remain in Denmark, but Wunderlich will be reburied in Germany.[8]

2 The Burning Brigade’s Tunnel

Near the end of World War II, the Nazis knew they had lost. In Lithuania’s Ponar forest, they wanted to erase a camp where around 100,000 people had died. Eighty Jewish prisoners were brought from other locations to exhume and burn the bodies. The men handed this gruesome duty were called the Burning Brigade. After months, the breaking point came when the workers started finding family members inside the mass graves. For 76 nerve-racking days, the brigade dug a secret escape tunnel with spoons and whatever else they could find. On the moonless night of April 15, 1944, the prisoners dashed for freedom. Although they were overheard inside the tunnel, they struggled on through two barbed-wire fences and a minefield. The prisoners also ran from dogs and dodged bullets and mortars as they fled.[9] Twelve men escaped, and the testimonies of 11 allowed the entrance of the collapsed tunnel to be located years ago. In 2016, archaeologists found the rest with scanning technology. The spooned-out tunnel was nearly 34 meters (112 ft) long and showed the men’s monumental determination to survive despite the horrors they had endured.

1 World War Zero

A Bronze Age mystery surrounds eight major Mediterranean civilizations. All suddenly collapsed 3,200 years ago from war, famine, and domestic conflict. Geoarchaeologist Eberhard Zangger believes that “World War Zero” may have been responsible. According to his hypothesis, World War Zero caused Egypt’s disintegration. It also destroyed the Hittites, Minoans, Canaanites, Cypriots, Assyrians, Mycenaeans, and Babylonians. Their common enemy was an alliance among groups from western Asia Minor who spoke dialects of the Luwian language. After watching the Hittites and the Egyptian pharaohs fall, the Mycenaean Greeks launched successful attacks on the Luwians’ port cities. However, the Greeks’ homecoming was disastrous. The deputies they had left behind refused to abdicate, and the resulting civil war introduced the Greek Dark Ages.[10] Many scholars don’t accept that the Luwians were capable invaders or that World War Zero was possible. They believe that another unknown factor caused the eight cultures to collapse around the same time. However, Zangger believes that historical documents are supportive of his theory, including that the Luwians were likely the mysterious and destructive “Sea Peoples” mentioned in Egyptian writings. In Turkey, he has also identified sites that were possibly built by Luwians. Some of these sites are so large that they are visible from space. Read More: Facebook Smashwords HubPages