The Holy Tunic of Christ is said to have been worn by Jesus during or shortly before his Crucifixion. It is preserved at the Cathedral of Trier in Germany. In the Gospel of John, the soldiers cast lots on who would receive the tunic because it was woven in one single piece. Hence the name, the Seamless Robe. “Then the soldiers, when they had crucified Jesus, took His garments (ta himatia) and divided them into four parts, to every soldier a part, and the coat (kai ton chitona). Now the coat was without seam, woven whole from the top down. Therefore, they said among themselves, let us not tear it, but cast lots for it, whose it will become. Thus the saying in Scripture was fulfilled: they divided My raiment (ta imatia) among them, and upon My vesture (epi ton himatismon) did they cast lots” (John 19:23-24; quoting the Septuagint version of Psalm 21 [22]:18-19). According to legend, Helena, mother of Constantine the Great, discovered the seamless robe in the Holy Land in the year 327 or 328 along with several other relics, including the True Cross. According to different versions of the story, she either bequeathed it or sent it to the city of Trier, where Constantine had lived for some years before becoming emperor. (The monk Altmann of Hautvillers wrote in the 9th century that Helena was born in that city, though this report is strongly disputed by most modern historians.) The history of the Trier robe is certain only from the 12th century. On May 1, 1196, Archbishop Johann I of Trier consecrated an altar in which the seamless robe was contained. It is no longer possible to determine the exact historical path that the robe took to arrive there, so many hold it to be a medieval forgery. The various attempts at preservation and restoration through the centuries have made it difficult to determine how much of the relic (if genuine) actually stems from the time of Jesus. A scientific examination of the specimen has not been conducted. The stigmatist Therese Neumann of Konnersreuth declared that the Trier robe was authentic.

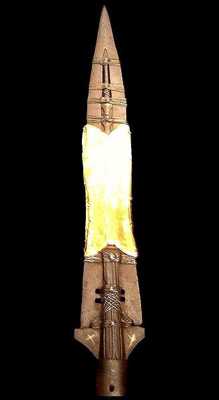

The Holy Lance (also known as the Spear of Destiny, Holy Spear, Lance of Longinus, Spear of Longinus or Spear of Christ) is the name given to the lance that pierced Jesus’ side as he hung on the cross in John’s account of the Crucifixion. The lance (Greek: λογχη, longche) is mentioned only in the Gospel of John (19:31–37) and not in any of the Synoptic Gospels. The gospel states that the Romans planned to break Jesus’ legs, a practice known as crurifragium, which was a method of hastening death during a crucifixion. Just before they did so, they realized that Jesus was already dead and that there was no reason to break his legs. To make sure that he was dead, a Roman soldier (named in extra-Biblical tradition as Longinus) stabbed him in the side. … but one of the soldiers pierced his side with a lance (λογχη), and immediately there came out blood and water. —John 19:34

Saint John tells that, in the night between Maundy Thursday and Good Friday, Roman soldiers mocked Christ and his Sovereignty by placing a thorny crown on his head (John 19:12). The crown housed in the Paris cathedral is a circle of canes bundled together and held by gold threads. The thorns were attached to this braided circle, which measures 21 centimeters in diameter. The thorns were divided up over the centuries by the Byzantine emperors and the Kings of France. There are seventy, all of the same type, which have been confirmed as the original thorns. The relics of the Passion presented at Notre-Dame de Paris include a piece of the Cross, which had been kept in Rome and delivered by Saint Helen, the mother of Emperor Constantine, a nail of the Passion and the Holy Crown of Thorns. Of these relics, the Crown of Thorns is without a doubt the most precious and the most revered. Despite numerous studies and historical and scientific research efforts, its authenticity cannot be certified. It has been the object of more than sixteen centuries of fervent Christian prayer.

In the Christian tradition, the True Cross refers to the actual cross used in the Crucifixion of Jesus. Today, many fragments of wood are claimed as True Cross relics, but in most cases it is hard to establish their authenticity. The spread of the story of the fourth century discovery of the True Cross was partly due to its inclusion in 1260 in Jacopo de Voragine’s very popular book The Golden Legend, which also included other tales such as Saint George and the Dragon. Pieces of the purported True Cross, including the half of the INRI inscription tablet, are preserved at the ancient basilica Santa Croce in Gerusalemme in Rome. Very small pieces or particles of the True Cross are reportedly preserved in hundreds of other churches in Europe and inside crucifixes. Their authenticity is not accepted universally by those of the Christian faith and the accuracy of the reports surrounding the discovery of the True Cross is questioned by many Christians.

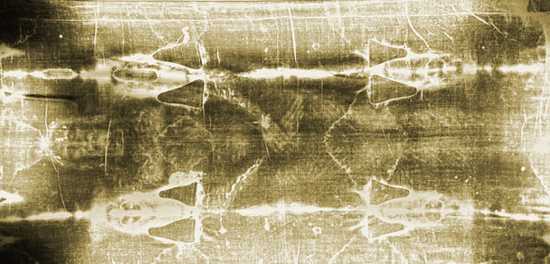

The Shroud of Turin is the best-known relic of Jesus and one of, if not the, most studied artifacts in human history. Believers contend that the shroud is the cloth placed on the body of Jesus Christ at the time of his burial, and that the face image is the Holy Face of Jesus. Detractors contend that the artifact postdates the Crucifixion of Jesus by more than a millennium. Both sides of the argument use science and historical documents to make their case. The striking negative image was first observed on the evening of May 28, 1898, on the reverse photographic plate of amateur photographer Secondo Pia, who was allowed to photograph it while it was being exhibited in the Turin Cathedral. The Catholic Church has neither formally endorsed or rejected the shroud, but in 1958 Pope Pius XII approved of the image in association with the Roman Catholic devotion to the Holy Face of Jesus.

The Iron Crown of Lombardy is both a reliquary and one of the most ancient royal insignia of Europe. The crown became one of the symbols of the Kingdom of Lombards and later of the medieval Kingdom of Italy. It is kept in the Cathedral of Monza, in the suburbs of Milan. The Iron Crown is so called from a narrow band of iron about one centimeter (three-eighths of an inch) within it, said to be beaten out of one of the nails used at the crucifixion. The outer circlet of the crown is of six segments of beaten gold partly enameled, joined together by hinges and set with twenty-two gemstones that stand out in relief, in the form of crosses and flowers. Its small size and hinged construction have suggested to some that it was originally a large armlet or perhaps a votive crown; for others, the small size of the present crown was caused by a readjustment after the loss of two segments, as described in historical documents.

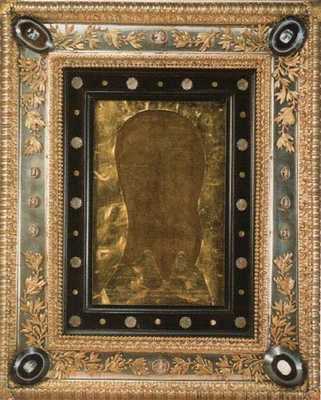

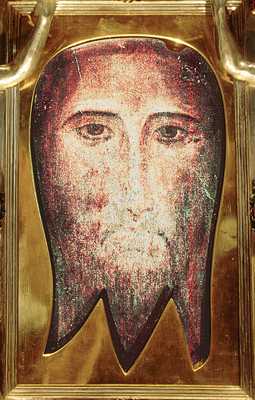

The Veil of Veronica, which according to legend was used to wipe the sweat from Jesus’ brow as he carried the cross is also said to bear the likeness of the Face of Christ. Today, several images claim to be the Veil of Veronica. There is an image kept in Saint Peter’s Basilica in Rome which purports to be the same Veronica as was revered in the Middle Ages. Very few inspections are recorded in modern times and there are no detailed photographs. The most detailed recorded inspection of the 20th century occurred in 1907 when Jesuit art historian Joseph Wilpert was allowed to remove two plates of glass to inspect the image.

The Scala Sancta (English: Holy Stairs) are, according to the Christian tradition, the steps that led up to the praetorium of Pontius Pilate in Jerusalem, which Jesus Christ stood on during his Passion on his way to trial. The stairs were, reputedly, brought to Rome by St. Helena in the 4th Century. For centuries, the Scala Santa has attracted Christian pilgrims who wished to honor the Passion of Jesus. It consists of twenty-eight white marble steps, now encased by wooden steps, located in a building which incorporates part of the old Lateran Palace, located opposite the Basilica of Saint John Lateran. They are located next to a church which was built on ground brought from Mount Calvary. The stairs lead to the Sancta Sanctorum (English: Holy of Holies), the personal chapel of the early Popes in the Lateran palace, known as the chapel of St. Lawrence.

The Image of Edessa, as known as the Mandylion, was allegedly sent by Jesus himself to King Abgar V of Edessa to cure him of leprosy, with a letter declining an invitation to visit the king. The story of this image is the product of centuries of development during which the image was lost and reappeared several times. Today two images claim to be the Mandylion, one is the Holy Face of Genoa at the Church of St Bartholomew of The Armenians in Genoa, the other the Holy Face of San Silvestro, kept in the Church of San Silvestro in Capite in Rome up to 1870 now in the Matilda Chapel of the Vatican Palace, The theory that the object venerated as the Mandylion from the sixth to the thirteenth centuries was in fact the Shroud of Turin has been the subject of debate, but is now mostly rejected as a hypothesis.

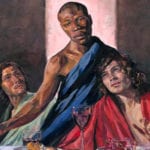

The Holy Grail is a sacred object figuring in literature and certain Christian traditions, most often identified with the dish, plate, or cup used by Jesus at the Last Supper and said to possess miraculous powers. The connection of Joseph of Arimathea with the Grail legend dates from Robert de Boron’s Joseph d’Arimathie (late 12th century) in which Joseph receives the Grail from an apparition of Jesus and sends it with his followers to Great Britain; building upon this theme, later writers recounted how Joseph used the Grail to catch Christ’s blood while interring him and that in Britain he founded a line of guardians to keep it safe. The quest for the Holy Grail makes up an important segment of the Arthurian cycle, appearing first in works by Chrétien de Troyes. The legend may combine Christian lore with a Celtic myth of a cauldron endowed with special powers. The Grail legend’s development has been traced in detail by cultural historians: It is a legend which first came together in the form of written romances, deriving perhaps from some pre-Christian folklore hints, in the later 12th and early 13th centuries. The early Grail romances centered on Percival and were woven into the more general Arthurian fabric. Some of the Grail legend is interwoven with legends of the Holy Chalice. The work of Leonardo da vinci presents the Holy Grail as derivative of sang real literally meaning holy blood, i.e blood lineage of Jesus with his alleged wife Mary Magdalene which has been kept hidden to date.