Although it might be efficient and incredibly cruel, it lacks that certain “flashiness” which usually grabs the public’s attention. Crime aficionados love an intricate murder plot or an unforgettably bloody crime scene. Poison doesn’t give us such hot-blooded drama; it just gives us the chills. That’s why these next cold-blooded killers are all but forgotten today.

10 Louisa CollinsThe ‘Borgia Of Botany’

Louisa Collins had the ignominious honor of being the last woman hanged in New South Wales, Australia, back in 1889. She married young to Charles Andrews, and together with their seven children, they lived in a house in Botany, today a suburb in Sydney. The family had a bit of spare room and often took in boarders to make a little extra cash. Rumors soon sprang up that Louisa was a bit too “familiar” with some of the male boarders. In particular, her liaison with one Michael Collins was discovered by her husband. Charles promptly threw Michael out of his home. But soon afterward, Charles fell ill and died within a week. Louisa didn’t wait long. Just three months after Charles’s death, she married Michael Collins.[1] The new relationship didn’t last. Within a few months, Michael fell ill as well. He died shortly thereafter with symptoms similar to that of his predecessor. The circumstances were suspicious enough to warrant an autopsy which revealed that Collins had died of arsenic poisoning. Louisa was immediately charged with the crime, although it took two years and four different juries before she was found guilty. The “Borgia of Botany,” as she was dubbed by the media, was finally convicted following testimony from her daughter, who claimed that Louisa had bought an arsenic-based poison called Rough On Rats.

9 Elisabeth WieseThe ‘Angel-Maker Of St. Pauli’

Some of the most vile killers in history were involved with the dubious practice of baby farming. Women would take custody of unwanted children, typically infants, in exchange for a lump sum or a periodic payment. However, particularly in the case of one-time payments, there was little incentive for the women to provide quality, long-term care for the children. Sometimes, the most efficient solution was to simply kill them and find new clients. The parents wanted nothing to do with their children, so they rarely checked up on them. That’s how certain killers like the Finchley baby farmers or Amelia Dyer murdered dozens, even hundreds, of children before being caught. More obscure was Elisabeth Wiese, known as the “angel-maker of St. Pauli” after the Hamburg suburb where she plied her murderous trade. She had already spent time in jail for trying to kill her husband. When she got out, Wiese started a lucrative baby farming business. She took in children from rich families afraid of scandal with the promise of finding these youngsters new families. Instead, she killed the babies with morphine and disposed of them in the kitchen stove.[2] At one point, she even forced her daughter, Paula, into prostitution and killed her baby when Paula got pregnant. Eventually, police caught wind of Wiese’s suspicious business and found enough evidence, along with Paula’s testimony, to convict her. Wiese was beheaded in 1905.

8 Adolf Seefeld‘Onkel Tick Tack’

It’s hard to determine the extent of Adolf Seefeld’s crimes. Since he was active during 1930s Germany and preyed on young boys, the Nazi Party used him as anti-homosexual propaganda. His life is also poorly documented since he worked as a traveling watchmaker, moving from town to town. Some records claim that Seefeld committed his first murder in 1908 but managed to escape conviction. He spent most of his adult years in prison on various charges for child molestation. When he was arrested for murder in 1935, Seefeld was convicted of poisoning 12 boys with a homemade concoction and burying them in the woods.[3] Some estimated that his real body count was around 30 or even higher. Seefeld’s trial was a big win for the Nazi Party’s efforts to label homosexuals as “enemies of the state.” The papers named him “Uncle Tic Toc” due to his occupation. Some of them echoed Nazi claims that these kinds of “perverse tendencies” often resulted in murder and that it would be better if such “beasts” were neutralized before having the chance to do any harm.

7 Caroline Grills‘Aunt Thally’

At first glance, Caroline Grills (“Auntie Carrie” to her family) looked like your typical sweet little old lady. Short in stature, with a friendly smile and thick glasses, her biggest pleasure in life seemed to be serving tea and biscuits. Unknown to her guests, though, that tea was often laced with thallium, a common rat poison. Auntie Carrie was already a grandmother in her sixties when she was charged in 1953 with the attempted murder of her sister-in-law Eveline Lundberg and Lundberg’s daughter. Both exhibited symptoms of thallium poisoning as did another family member, John Downey, who alerted the police.[4] Investigators found several suspicious deaths in Grills’s family starting with her stepmother in 1947. Her husband’s brother-in-law, a cousin, and a friend of her stepmother all died within the next two years. While two had been cremated, investigators were able to dig up the other two and found traces of thallium. In the end, Grills was only convicted of one attempted murder and sentenced to life in prison. There, she became known as “Aunt Thally” due to her penchant for that particular poison.

6 Daisy de MelkerThe Plumber’s Wife

Back in 1923, Daisy de Melker led an unassuming life in Johannesburg, South Africa, with her husband, William Cowle, and her only surviving child, Rhodes Cecil. One day, Cowle felt ill so his wife gave him some Epsom salts. However, instead of getting better, his health kept deteriorating until he died of a cerebral hemorrhage. Even though he was a plumber, Cowle left behind a tidy sum inherited by his wife of 14 years, Daisy. A few years later, Daisy married another plumber, Robert Sproat. This marriage was much shorter. In November 1927, Robert also died of a cerebral hemorrhage. Despite his circumstances mirroring those of William Cowle, both deaths were ruled natural causes and Daisy, again, walked away with money from his inheritance. In 1931, Daisy de Melker married her third plumber, Sydney Clarence. A year later, another family member met an untimely demise. However, this time it wasn’t her husband but her 20-year-old son, Rhodes. Three suspicious deaths in eight years was enough to attract the attention of police, and from there, it wasn’t hard to prove Daisy’s involvement. All three bodies showed traces of strychnine, and sales of the poison were traced back to her.[5] In the end, though, Daisy de Melker was only convicted of her son’s murder. She was hanged in 1932.

5 Bertha GiffordThe Angel Of Death

Regarded as a friendly housewife, Bertha Gifford was known to visit her sickly relatives and neighbors in Catawissa, Missouri, to care for them. However, many of her patients never got better. Too many, in fact, which is why Gifford was arrested in 1928 following a killing spree that had lasted up to three decades. Nobody knows for sure how many people Gifford killed. She was charged with three murders, named in six more, and suspected of up to 17. Gifford confessed to killing 48-year-old Edward Brinley and seven- and eight-year-old brothers, Elmer and Lloyd Shamel. According to Gifford, she poisoned them with arsenic to ease their pain as they were all suffering from severe stomachaches.[6] However, the boys’ father, George Shamel, testified that both were feeling fine before visiting the Giffords. Bertha seemingly had no preference when targeting people. Her oldest victim was 72 years old, while her youngest was just 15 months. Although unproven, it was highly suspected that Gifford’s first victim was her first husband, Henry Graham. Despite her confession, Bertha Gifford was found not guilty by reason of insanity and spent the rest of her life at Farmington State Hospital.

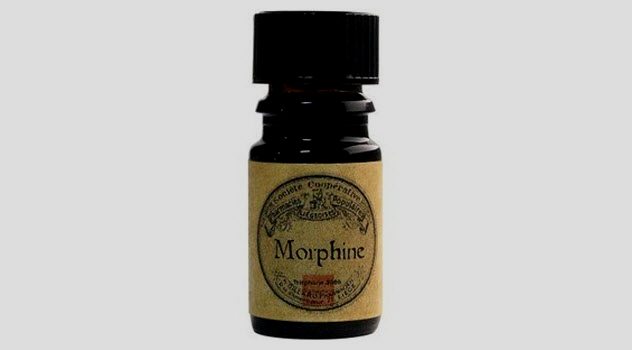

4 Robert BuchananThe Morphine Murderer

Born in Nova Scotia, Dr. Robert Buchanan set up his practice in New York in 1886. His first marriage broke down due to his preference for women and drinking. He then married Anna Sutherland, a former brothel madam who was 20 years older than he was. But she had amassed a sizable fortune. As his status grew, Buchanan became embarrassed by his wife but was still very fond of her money. After Anna threatened to cut him out of her will, the solution for Buchanan became quite clear—his wife had to go. Soon afterward, Anna fell ill and died days later. The coroner certified the cause of death as a brain hemorrhage, and Buchanan inherited $50,000. By pure chance, a reporter named Ike White heard of Anna Sutherland’s death while visiting the coroner’s office. He reached out to Anna’s former partner, who convinced White that Buchanan was a murderer. In turn, White tried to convince Sutherland’s coroner that Anna had been poisoned with morphine. But the coroner refused to believe it based on the lack of pinpoint pupils. At one point during the investigation, someone recalled that Buchanan had once decried Carlyle Harris, another morphine poisoner, as a “stupid amateur” for not knowing how to get rid of the signature pinpoint pupils.[7] Based on this, White looked into possible methods to achieve this and concluded that a few drops of atropine prior to death would be enough. Through a newspaper campaign, White convinced the New York coroner to exhume Anna Sutherland’s body and reexamine it. This time, the result was clear—death through morphine overdose. Buchanan was convicted and executed in 1895.

3 Lydia Sherman‘The Derby Poisoner’

In 1872, Connecticut resident Lydia Sherman found herself charged with poisoning her third husband, Horatio Sherman. Curiously, she claimed that it was an accident and that she had never intended to kill her husband. She only wanted to poison his children (plus all the people she killed beforehand). Lydia Sherman lived by a simple creed: If a problem comes along, use arsenic. Her first husband, Edward Struck, was a police officer in New York before being fired and falling into depression. Concerned over the loss of income and the despondent husband, Lydia solved both problems with a life insurance policy and rat poison in his food.[8] The couple had five children together—three young ones and two teenagers from Edward’s previous marriage. The young ones were the first to go as they were the biggest burden. Still struggling to make ends meet, Lydia also killed the other two and then moved to Connecticut to look for a new husband. She married an elderly farmer named Dennis Hurlburt in 1868. However, the marriage wasn’t a happy one, so Lydia used the insurance policy/rat poison combo again in 1870. She then married Horatio Sherman in Derby, Connecticut. A recent widower, Sherman had two young children. Lydia wasn’t too fond of the kids, so she poisoned both of them. Sherman began drinking heavily after his children’s sudden deaths. According to Lydia, that’s how he killed himself—by drunkenly putting poison in his cider because he had mistaken the poison for sodium bicarbonate. In the end, Lydia Sherman got life in prison, convicted of the only murder she denied involvement in.

2 Valorous P. CoolidgeThe Waterville Poisoner

Dr. Valorous P. Coolidge had a thriving practice in the city of Waterville, Maine, during the mid-19th century. Despite this, he was a man constantly living above his means and, as a result, often found himself in debt. In 1847, the doctor was indebted $2,500 to a cattle dealer named Edward Mathews. On September 29, he came round to Coolidge’s place and unsuspectingly drank a brandy laced with prussic acid, better known today as hydrogen cyanide.[9] His body was found the next day in an empty cellar with several head wounds and a missing wallet. Coolidge was interviewed as a witness since people knew that Mathews had come to his office. However, it seemed that Coolidge’s ploy to make it look like a robbery-gone-bad had worked as local investigators allowed him to perform the autopsy on his own murder victim. During the procedure, Coolidge concluded that the wounds to the head could have been fatal, although he couldn’t say for certain. His real goal was to get rid of the stomach contents. Coolidge had them removed from the room due to their strong smell of brandy. Later on, he claimed that they had been out too long to provide any accurate information. Despite Coolidge’s decision, someone still sent the stomach contents over to a Professor Loomis for analysis. He quickly detected traces of prussic acid. Upon investigating the rest of the body, Loomis discovered that the head wounds were clearly inflicted after death, something Coolidge would have known. The doctor immediately became the number one suspect. He committed suicide in jail before being convicted.

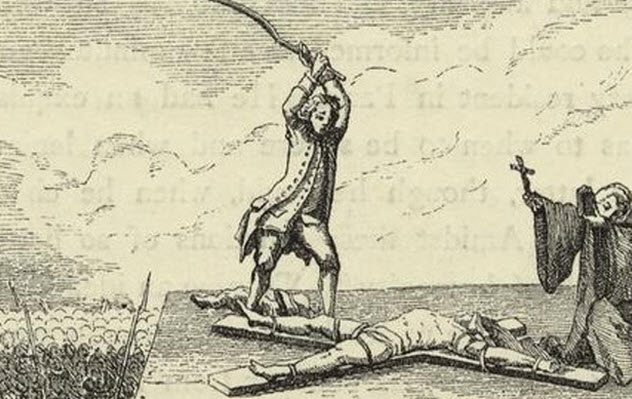

1 Antoine DesruesThe Ghastly Grocer

Although barely remembered today, the name Antoine Desrues (sometimes Derues) gained plenty of infamy in mid-18th century Paris as a cause celebre. Mr. and Mrs. de Lamotte were looking to sell their estate at Buisson-Souef and move to Paris to secure their son a position at the king’s court. When they first met Desrues, he introduced himself as interested buyer Mr. Desrues de Cyrano de Bury, lord of Candeville. His wife was supposedly part of the distinguished Nicolai family and was just about to receive a lavish 250,000 livres inheritance. In truth, Desrues was a penniless grocer already heavily in debt. However, he was convincing as an aristocrat and the de Lamottes were easily swayed by his charm. Even after Desrues missed his first payment, he managed to persuade them that it was all the fault of lawyers who kept delaying his wife’s inheritance. Eventually, Mrs. de Lamotte and her son came to Paris to obtain the money. Desrues came up with a plan to secure the estate permanently. He intended to use borrowed money to make a fake payment and then claim that Mrs. de Lamotte had taken the money and run away with a lover while her son had gone to Versailles.[10] Of course, for this to work, both Mrs. de Lamotte and her son had to disappear. In the following weeks, both fell ill and died under the care of Desrues. His ruse worked at first, and many people believed that Mrs. de Lamotte had run away. Her husband, however, was not one of them. Only after Desrues came to Buisson-Souef to evict Mr. de Lamotte did he see the grocer’s true colors. Mr. de Lamotte came to Paris and used his connections to start an investigation. It all ended when police found the wife’s body buried in the cellar of a home that Desrues had rented using a fake name. The grocer-turned-aristocrat was broken on the wheel and burned alive.